Naval History Homepage and Site Search

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

INTRODUCTION

1. From the passage of the Naval Appropriations Act of April 4, 1911, the Bureau was responsible for the design and construction of all public works and public utilities for the United States Navy, regardless of the areas of responsibility of the other bureaux. 2. Before 1917, this work was confined to the United States, but was extended overseas thereafter. 3. During the war years the Bureau experienced a 'phenomenal' growth in material and personnel. 4. The history of the Bureau from 1898 showed that it had recognised the inadequate nature of the number and type of shore establishments required for a major war. In particular, the dry-docks were too small to accommodate the new ships. The Bureau had begun a programme to build four large graving docks and one floating dock. This program was not completed until the opening of the dock at Pearl Harbor in 1919. Other projects diverted funds - especially during the war years. 5. The value of the docks and other shore facilities was given as: In 1897- $53m

In 1913- $191m In 1916-1918 the value rose from $211m to $469m An additional $70m funding was provided for investment in private shipyards and machinery manufacturers. CHAPTER

I : THE BUREAU OF YARDS AND DOCKS

Executive personnel of the Bureau. The Chief, Rear-Admiral Parks at centre  Bureau personnnel This chapter outlines the changes in the organisation of the bureau, and then provides information on the personnel employed in the bureau. Organisation

Before July 1st, 1916, the entire staff of the bureau consisted of: Chief of the Bureau

Chief Clerk small number of officers of the Corps of Civil Engineers 63 civilians including 4 female. To meet the expected demands of war, the bureau was organised into six divisions, each of which dealt with a specific area of responsibility. They were: Office of Assistant Chief

Division of Mechanical, Electrical and Routine Design Division of Special Designs and Projects Construction Division Maintenance and Operations Division Clerical Division On March 23rd, 1917, the divisions were reduced to three: Design

Construction Maintenance Under whom there would be

seven project managers. Their areas of responsibility

were:

New Naval Bases and Development of Existing Bases. Radio, Marine Corps, Fuel Oil, Medical Requirements, Routine Design, Dry Docks, Power Plants, Washington Yard, and Sub-surface surveys. Shipbuilding Projects and Improvements, and Gun Shop, Washington. Armor Plant and Projectiles Plant, Charleston WV. Facilities for Aviation and Submarines, Patrol Bases. Ordnance Facilities and Store Houses. Naval Academy, Research and Development Laboratory, Design Division. A final re-organisation took place In October 1917. Ten project managers were appointed. They covered the following areas: Dry Docks

Armor and Projectile Plants Naval Academy Magazines and General Ordnance Facilities Aviation and Submarine Bases Shipbuilding and Yard Development Marine Corps, Fuel Oil, Routine Design Hospitals Power Plants Training Camps Personnel

Strength

Recruiting was made easier by permission to recruit personnel from the United States Naval Reserve. This produced 197 male and 121 female members of staff. Some 24 distinguished, well-qualified engineers could be - and were - recruited from civilian life; and staff were forbidden from enlisting in the combat units of the armed forces. The growth of the bureau's personnel is illustrated thus:

* Technical staff -

mainly draughtsmen

The distribution of technical staff between the various areas of work on January 1st, 1919 was: Armor & Projectiles 16

Shipbuilding 60 Magazines, Store Houses, General Ordnance, Aviation, Submarine Bases 73 Training camps 16 Marine Corps, Fuel, Radio & Routine 22 Hospitals 23 Dry Docks 5 Power Plants 27 CHAPTER

II: THE CORPS OF CIVIL ENGINEERS, UNITED STATES NAVY

A small number of civilian engineers were employed by the Navy Department before 1867. In that year, an establishment of 10 uniformed civil engineers was approved by Congress. This total was increased to 18 in 1898, and then to 40 in 1903. With war imminent, an act of August 23rd 1916, permitted to recruitment of civilians and reservists into the Corps. By November 11th, 1918, the total strength was: 74 regular officers

20 temporary officers [ex civilians] 100 reserve officers for a total of 204. Civil engineer officers were employed either at the Bureau in Washington, or at the various navy yards around the country. Note: CEC - Civil Engineer

Corps

The inadequate accommodation provided by Bancroft Hall [designed for 500 midshipmen but having to provide places for 1,200 was remedied. The construction of two new accommodation blocks was authorised on March 4th 1917 with contracts signed on July 13th. The new blocks were completed in May and September 1918. They provided an extra 1,200 places, doubling the capacity to 2,400 at a cost of $3,925,000. A new classroom block for seamanship and navigation was completed at the same time for $1,000,000; as was a new power plant and distribution system. CHAPTER

IV: NAVAL TRAINING CAMPS

In the spring of 1917, the US Navy possessed 4 naval

training stations with a total capacity of 6,000 trainees.

This was recognised as insufficient for war-time

expansion, and a major part of the Bureau's work to

rectify this deficiency.

The four training stations were: Great Lakes opened 1911

capacity=3,000 [received 28,000 in July 1918]

Newport, RI opened 1881 capacity=2,000 Yerba Buena, San Francisco opened 1889 capacity=500 St, Helena, Norfolk Navy Yard opened 1908 capacity=500 They had been established because of the greater need for technical training: a function which could not be performed by the existing training hulks. The Bureau's wartime target was to provide an extra 40 training establishments with a winter capacity of 191,000 and a summer capacity of 205,000 [some camps were tented]. The original estimated cost was $1.5m but the actual expenditure was $75m. Up to 50,000 men were employed in the construction work. Design work began immediately after the declaration of war, and contracts began to be signed in May 1917. Three existing sites were developed at great speed: Hampton Roads 10,000

places 3 1/2 weeks.

Philadelphia Navy Yard 5,000 places 3 weeks. Brooklyn Navy Yard 3,000 places 30 days. Largely built of wood, most of the new camps were built with standard-designed buildings, and organised into pre-determined groups - administration; isolation [for new recruits]; main regimental; services; hospital; education and recreation. The bulk of the chapter lists the major projects by Naval District, beginning with the 1st in New England, and ending with the 13th in Washington State. 1st Naval District, Boston Receiving Ship Boston,

Commonwealth Park, Boston - opened 4.17.

Training Camp Bumpkin Island - opened 5.17. Training Camp, Hingham - opened 10.17. Harvard Radio School - opened 4.17. Fuel Oil School, Quincy - opened 6.18. Prison Camp, Portsmouth NH - opened 4.18, enlarged by 12.18. 2nd Naval District, Newport, RI Training Station, Newport

RI [Coasters Harbor Island] - enlarged.

Coddington Point, Newport RI - not completed until 1920. Cloyne Field, Newport RI opened 5.17. also Submarine Base, New London, CT [see later chapter]. 3rd Naval District, New York Initially, trainees were

dispersed amongst old ships in New York, and in

temporary accommodation in New York City. This included

tented accommodation at Tarrytown and Summerville, and

the Bensonhouse hotel.

Pelham Bay Park

capacity=5,000, opened 11.17, extended to 8,000 by

11.18.

4th Naval District, PhiladelphiaPhiladelphia Navy Yard -

new camp began 5.17, places for 6,400 by 10.18.

Wissahickon, Cape May, NJ - places for 2,000 by 8.17, further extension planned but not completed. Cooking School, Naval Home, Philadelphia - expanded during 1918. 5th Naval District, Norfolk, Va Training Station Norfolk -

increased to 7,679 placed but less important once next

entry was completed.

Naval Operating Base, Hampton Roads - opened October 12, 1917 and expanded to 12,693 places by 11.18. Ensigns' School, Annapolis - added to Naval Academy with places for 450 Naval Reserve officers. 6th Naval District, Charleston Charleston Navy Yard -

buildings added to Receiving Ship to provide 1,000

places by 6.17 and 4,000 by the end of hostilities.

7th Naval District, Miami Key West, FL -

lightly-built barracks for 1,000 opened by 6.17.

8th Naval District, New Orleans New Orleans, LA - tented

accommodation for 1,000 and more permanent spaces for

250 added later.

9th Naval District, Great Lakes Great Lake Training

Station [33 miles north of Chicago] - expanded by 10.18

to 1.200 acres with 775 buildings in 22 sub-groups.

Accommodated 50,000 at a cost of $17,127.00.

Training Camp Detroit - opened 6.18 with crews of 'Eagle Boats', 200 officers and 1,000 enlisted men. Note:

from 1911, 9th/10th/11th Naval Districts covered the

Great Lakes. San Diego was later designated the 11th

and the 10th was discontinued.

11th Naval District, San Diego Training Camp San Diego -

mainly tented accommodation for 4.000 from 4.17.

Training Camp San Pedro - originally for 1,000 who were transferred to the submarine base, became tented accommodation for 2.400. Note:

San Diego was developed during WW1 and from 1917 was

designated 12th Naval District [South]. In

1919 it became 11ND as San Diego was developed as

main base for Pacific Fleet.

12th Naval District, San Francisco Naval Training Station,

San Francisco - expanded to 5,000 places.

Receiving Ship Mare Island - expanded from 600 to 5,600 places by 9.17. 13th Naval District, Seattle Training Camp Puget Sound

Navy Yard - expanded by 12.17 for 5,000.

Training Camp Seattle - planned 6.17, held 3,000 by 11.18. The last nine pages of this chapter is made up of an account by Lt.Cmdr Bolles regarding the construction of the training camp at Coddington Point, Newport, RI. The provision of new facilities for the USMC began with three projects in Philadelphia: Extension to the

Quartermaster Storehouse - completed 9.17.

New barracks at Philadelphia Navy Yard for 400 marines - completed 11.17. Advanced base storehouse - completed 12.17. New barracks were built: American Legation, Peking,

China

Naval Station, Key West Pearl Harbor [including quartermaster storehouse] Major projects were: Expeditionary Base, San

Diego with full range of facilities for 1,700 marines at

cost of $5m.

Marine Guard Barracks at Portsmouth NH - for 545 marines, completed 11.118 Training Base at Quantico, Va - for 6.900 marines, completed 11.18 Training Base at Parris Island, SC - completed 3.18 for 3,000 marines, extended to 4,100 by 12.18 97

Prewar plans for a two 5,000 bed hospitals - one on the

east coast, and the other on the west coast, were

abandoned on the outbreak of war. A range of smaller

emergency hospitals would be built instead.CHAPTER VI. EMERGENCY HOSPITAL CONSTRUCTION click here for an introduction to the influenza epidemic, the men who died, and hospitals which treated them

By extending existing hospitals, and constructing temporary ones, 27 hospitals were operational by the end of the conflict. This program involved the construction of 500 new buildings [mostly of standard wood construction] to provide places for 17,000 patients. The cost was $21m with an additional $550,000 spent on medical supply depots. Dispensary facilities were created at all shore stations. The hospitals were: Portsmouth, NH 225 beds

Chelsea, Mass. 1,000 Newport, RI 312 New London, Conn. 150 Brooklyn, NY 750 Ward's Island, NY 800 Pelham Bay, NY 750 Grays' Ferry, Philadelphia 300 League Island, Philadlephia 775 Cape May, NJ 200 Washington DC 300 Quantico, Va 300 Annapolis, Md 100 Norfolk, Va 1,275 Hampton Roads, Va 750 Charleston, SC 715 Parris Island, SC 185 Pensacola, Fl 200 Key West, Fl 150 Gulfport, Miss 150 New Orleans, La 200 Great Lakes, Ill 1,500 Fort Lyon, Colo figures not provided Mare Island, Cal 550 San Diego, Cal 500 Puget Sound, Wa 100 Pearl Harbor figures not given The construction of 3 other hospitals was cancelled: Halifax, NS, Canada

Hingham, Mass Yorktown, Va With the despatch of 200 portable buildings and local construction, the following hospitals were provided overseas. United States Naval Base

Hospitals

No.1, Brest, France

No.2, Strathpeffer, Scotland No.3, Leith, Scotland No.4, Queenstown, Ireland [completed Nov.15, 1918 for 500 patients] No.5, Brest, France United States Naval

Hospitals:

L'Orient, France

Pauillac, France London, England Gibraltar Cardiff, Wales Plymouth, England Genoa, Italy Corfu, Greece All of these hospitals

were closed 1919/20.

This chapter provides many plans and photographs of the above hospitals. CHAPTER

VII: GENERAL DEVELOPMENT OF YARDS AND STATIONS

On May 2, 1916, the Navy Secretary set up the Board for the Development of Navy Yard Plans. This was in response to the very large 1916 new construction plans. The board developed a Type Plan to be applied to each navy yard. Plans were approved for: Norfolk Navy Yard

[February 5th, 1917]

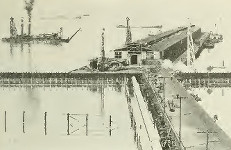

Philadelphia Navy Yard [May 1st, 1917] Puget Sound Navy Yard [May 25th, 1917] new Naval Operating Base, Hampton Roads [July 1917]. The main proposals for each navy yard were: Naval Operating Base,

Hampton Roads

Construction of a

complete new base which would include aviation,

submarine, and fleet supply facilities.

Purchase of 474 acres at Sewell's Point. Construction of barracks for 7,500. After dredging and coffer

dams - the construction of a waterfront which included

six piers, each 1,400 feet long - to accommodate

battleships; and a submarine base

This major work continued after the end of hostilities to create the main base for the postwar Atlantic Fleet. Norfolk Navy Yard

New 1,000 foot dock.

New shipbuilding slips and industrial plant. Philadelphia Navy Yard Many general

improvements.

New York Navy Yard Extra shipbuilding

facilities on a restricted site.

Puget Sound Navy Yard Purchase of land for

future development under plans drawn up in 1916

Mare Island Navy Yard More shipbuilding

facilities.

A causeway linking the yard with Vallejo. Portsmouth Navy Yard

Minor improvements.

Naval Air Station, Pensacola Improvements to berthing

and quays.

Great Lakes Naval Training Station A breakwater and

improved quays.

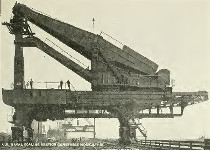

Planning for a proposed naval base at San Francisco, General improvements to moorings-especially on the west coast for the Pacific Fleet. 155 CHAPTER VIII; SHIPBUILDING AND REPAIR FACILITIES New York Naval Yard

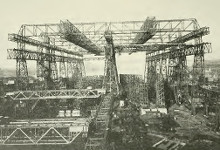

Philadelphia Navy Yard As a result of the 1916 ship building program, the previous capacity for the construction of battleships which was limited to two navy yards and a few private firms needed to be increased. The Naval Appropriations Act of August 29, 1916 authorised the expenditure of $6m for the improvement of the yards designated as suitable for the construction of large warships. They were Norfolk, Philadelphia, Boston and Puget Sound. Further funds were authorised as the work developed - $12m on March 4th, 1917; $1,75m on March 28th 1918; $10m in July 1918. The total expenditure by 1920 was $43,549.000. The main proposals were: Portsmouth Navy Yard: four

additional submarine slips.

Boston Navy Yard; continued construction of auxiliaries. New York Navy Yard; one additional slip for battleship construction. Philadelphia Navy Yard: slips for construction of two battleships. Norfolk Navy Yard: slip for construction of one battleship. Charleston Navy Yard: three additional destroyer slips. Puget Sound Navy Yard: one battleship construction dock. Mare Island Navy Yard: expansion of existing slip to construct one battleship Most of these projects

were not finished until after 11.18.

Puget Sound Navy Yard,

Wash

A diagram on pages 160-161 illustrates the resulting increase in building capacity.

Charleston Navy

Yard, SC

The principal areas of work were: Workshops: Structural shops

Foundries Pattern shops and storage areas Machine shops Galvanising plants Oxygen-hydrogen-acetylene generating plants Boat shop and improvements to the

gun shop at Washington Navy Yard

Shipbuilding:

Launching ways

improvements

Crane runways and overhead cranes New ways at Philadelphia New ways at Norfolk New ways at New York Shipbuilding dock at Puget Sound New ways at Mare Island Submarine ways at Portsmouth Destroyer ways at Charleston and Mare Island Minesweeper ways at Phildalphia and Puget Sound Fitting out piers and

cranes:

1,000ft x 100ft with

water depth of 40 ft

at Phildelphia

350 ton crane at Philadelphiaat Norfolk Auxiliary fitting out cranes at Puget Sound Waterfront facilities:

Tracks, streets, sewers

Extensive dredging and rebuilt quays Floating cranes Special locomotive cranes at New York [1], Philadelphia [2], Norfolk [1], Pearl Harbor [1] Marine railways to winch small vessels [up to destroyers] ashore for maintenance at Pearl Harbor, San Diego, Boston. Key West, Cape May, Guantanamo, Washington, Newport, Great Lakes, and Cavite. This chapter has many photos, charts and pull-out plans Norfolk Navy Yard, Va

*Nos 342, Hulbert and

343, Noa 28 June 1919

CHAPTER

IX: SHIPYARD AND INDUSTRIAL PLANT EXTENSIONS

In addition to modernisation of the navy yards, the Bureau provided funding for the extension and modernisation of the shipbuilding facilities of commercial enterprises, most of whom had built warships for the US Navy prior to 1917. This effort was encouraged by the need to produce large numbers of destroyers, submarines and small craft. A total of 45 projects were authorised at a cost of $71m. These projects came in one of three different financial and legal categories: Special Projects 'A'

improvements became property of the private company.

Plant extensions - government built which returned to the government at the end of contract. Special Projects 'B' improvements which reverted to government control after the end of the war. On page 217, there is a table which lists all 45 projects in terms of timing of funds, total funds, and main area of expenditure. Of these: 34 were for the

construction of destroyers, scout cruisers, submarines

and small craft.

2 were for the creation of storage for coal at naval bases 1 was for aircraft propellers 8 were for shafts and ordnance material The largest contracts were: $14m for the creation of

a new shipyard for Bethlehem Steel at Squantum, Quincy,

Mass. which became operational in January 1918. 35

destroyers were built by 1921.

$9m for an extension at Newport News, Va, with 3 slipways for battleships, 2 for battlecruisers, and 8 for destroyers. To this was added three new dry docks of 600/800/525 ft lengths This allowed contracts to be signed for 31 destroyers, 2 battlecruisers, 2 battleships, 8 tankers and 4 troopships $8m for the Erie Forge plant, Erie, Pa, which made shafts and gun fittings Another well-known contract was to the Ford Motor Company in Detroit, for $5.5m, to build a plant to deliver 100 'Eagle Boats' - patrol boats - of which 60 had been completed by 11.18. Other major contracts which are described in detail are: $4m to the New York

Shipbuilding Company, Camden, NJ for 10 single and 11

double slipways to fulfill contracts for 30 destroyers,

2 battleships and 1 battlecruiser.

To Bethlehem Steel, San Francisco, for the extension of yards at Risdon and Potrero, and the construction of a new yard at Alameda. This was for contracts to build 66 destroyers, 12 'S' class submarines, 6 'R' class submarines, and 2 scout cruisers. Allied to this wasthe development of two dry docks at Hunters Point at San Francisco for naval use. To Bethlehem Steel, Fore River, Mass. with 20 new slips, including 4 for destroyers, 10 for submarines, 1 for a battleship, and 5 others. This allowed contracts to be signed for 32 destroyers and 20 submarines. Non-shipyard contracts discussed in detail are: To Wellman, Seaver,

Morgan of Akron, Ohio for components of destroyers.

To railroad companies for coal storage at Sewell's Point, Va. and Newport News,Va. As with the previous chapter, there are extensive illustrations, and plans to accompany the narrative. CHAPTER

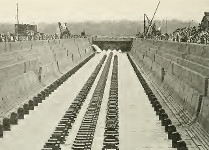

X: DRY DOCKS

*L to R - No.3 USS

Jupiter, No.6 SS Dio, No.7 SS Eastern Victor, No.4 USS

Mount Vernon

These were the most expensive single item in the range of facilities needed to support the fleet. In 1916, the United States Navy had an inventory of 21 dry docks. Only three were of a size suitable for battleships - one of 800 ft, and two of 740 ft. The rest were small and old with the smallest only 324 ft. long. The construction of the Balboa Dock for the Panama Canal increased confidence in tackling the engineering problems associated with the construction of large docks. Through a combination of new construction, purchase, and rental, the Navy Department acquired five large dry docks by 1921. Two smaller docks were acquired in the same time period. The new dry docks were: Dry Dock No. 4, Norfolk

Navy Yard:

Contracted signed

November 6, 1916

Completed April 1, 1919. Dimensions 1,011 ft. long; 144 ft. wide, depth of water 40 ft. Steel caisson built at Philadelphia Navy Yard Cost $5m Dry Docks Nos, 6 & 7, Norfolk Navy Yard Two docks built by the

Emergency Fleet Corporation which were made available

for naval use

Both 471 ft. long Dry Dock No 3, Philadelphia Navy Yard Duplicate of No. 4 Dock

at Norfolk

Encountered many obstacles because of soil and tides whilst under construction Not completed before 1921 Cost $6.3m Dry Dock No1, Pearl Harbor Because of problems

with the site, the dock was built in 15 steel

sections, which were launched and towed into place

between June 1915 and January 1918.

The caisson was fitted March 25, 1919 and the dock opened August 25, 1919 1000 ft. length Cost $5,064,000 South Boston Dry Dock Construction began by

Commonwealth of Massachusetts government. Purchase

authorised October 7th, 1918

1,176 ft long; 149 ft wide, and water depth of 43 ft Dry Dock, Hunters Point, San Francisco Built for commercial

shipping. Navy Department entered into rental contract

February 24, 1916, construction began soon thereafter,

and first naval use was October 14, 1918

1,005 ft long; 153 ft wide. This chapter contains much detailed information on the technical issues of dry dock construction. CHAPTER

XI: POWER PLANTS

The three areas of Bureau activity were the design and erection of new power plants, extensions to existing plants, and installation of the distribution systems. Contracts for 140 power plant projects were signed between April 6th, 1917 and November 11th 1918. The shortage of technical staff at the Bureau meant that most projects were partnerships between government and private firm. The two largest projects were the construction of new power plants for Norfolk Navy Yard and Philadelphia Navy Yard. The two coal-fired plants were identical in design but the Philadelphia plant was completed ahead of that at Norfolk. The work involved the construction and installation of boilers, turbines, and generators, as well as the supporting distribution systems. Other Navy yards received modifications and extensions to their existing plant. The most extensive worked was required at Charleston Navy Yard. Other yards were substantive work took place were: New York Navy Yard,

Boston Navy Yard, Mare Island Navy Yard, Puget Sound

Navy Yard, and at Pearl Harbor.

An urgent installation program was required to provide power plants for the new naval training camps. The most important were-Newport RI, Pelham Park NY, Hampstead Roads Va. Other major extensions took place at Torpedo Station Newport RI, Submarine Base New London Ct, Naval Aircraft Factory Philadelphia, Naval Academy Annapolis, New Orleans, and at the Indianhead Proving Ground in Maryland. As with earlier chapters, a considerable amount of technical detail can be found in this chapter. CHAPTER

XII: PUBLIC WORKS AT ORDNANCE STATIONS

Work was done at the request of the Bureau of Ordnance and involved not only the provision of manufacturing facilities but housing and other domestic needs as many stations were in remote areas. Ammunition Depots

The following major

ammunition depots required and were provided with new

facilities:

Hingham, Mass

Iona Island, NY Fort Mifflin, PA St. Juliens Creek, VA Puget Sound, WA Mare Island, CA Kuahua, Hawaii with more work at minor

depots at New London CT, Fort Lafayette NY, Lake

Denmark NJ, Charleston SC, Olongapo, PI and Cavite PI.

The success and speed of this work was assisted by the use of standardised designs for buildings. Torpedo Stations

The principal torpedo

station at Newport RI received extra facilities,

especially on the Goat Island site.

The Pacific torpedo station at Keyport, WA, received some extra facilities and improvements. In 1918, approval was given for the construction of a torpedo assembly plant on the Potomac river at Alexandria VA. It was completed later in 1918 at a cost of $1.3m. Standard torpedo storehouses were installed at the major naval yards and stations. Mine Depots

In January 1917 a

contract was awarded for a mine-filling plant at St

Juliens Creek, VA. It became operational in March 1918,

and shipped 73,000 mines for the North Sea Mine Barrage

without mishap.

Approval was given in 1918 for the construction of a large Mine Depot on an 11,000 acre site at Yorktown VA. Construction was underway by the end of hostilities. The depot was completed at a cost of $2.7m Naval Proving Ground and

Smokeless Powder Factory, Indianhead, MD

The capacity of the

smokeless powder factory was doubled. Work including

housing for the staff, a fresh water supply, and a

railroad connection to the network.

Naval Gun Factory and

Navy Yard, Washington DC

$7m was spent on updating

and extending existing facilities in a geographically

limited site.

The factory was able to continue its supply of guns to meet the fleet' s requirements throughout the conflict. CHAPTER

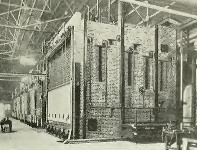

XIII: ARMOR AND PROJECTILE PLANT, CHARLESTON, WEST

VIRGINIA

see Development of Warship Armour  Projectile plant, West Virginia In August 1916, the decision was taken to build a plant for the manufacture of armor for the battleships being authorised. Existing private plants did not possess the capacity to produce armor in the quantities anticipated. The project was slowed down at the outbreak of war but resumed in mid 1918. The first task was to find a location for the plant. After surveying 200 sites, that at Charleston WV was selected. As the existing plants at Pittsburgh, Midvale, and South Bethlehem were of different designs, none could be used as a model for the new plant. Design work had to begin from scratch. After the outbreak of war, the government realised that the capacity to manufacture guns was insufficient to meet demands, and so, a new gun-making plant would be built alongside the armor plant. The basic gun would be manufactured at Charleston but finished off at the Washington Navy Yard. There is much technical detail in this chapter about the design of furnaces, machine shops, and on the storage of materials. Also discussion of the financial arrangements for the construction of the plant. Active construction of the armor plant began in July 1917 but the work was impeded by the geography of the site, by the lack of local labor, and by the lack of housing for imported labor. The problem of building a power plant was solved after the armistice. The US Army had no further need for the power plant at Nitro and it was transferred to the US Navy. Extra transmission lines connected the power plant with the armor/projectile plants. The gun manufacturing plant/projectile plant was constructed between August 1917 and May 1918, and was manufacturing 4 inch and 6 inch guns by the armistice. The armor plant was ready at the time of the book's publication in 1921, to begin manufacture of armor for the new battleships. CHAPTER

XIV: STORAGE FACILITIES

Before April 917 the Navy Department had recognised that the demand for storage facilities had outrun supply. The Bureau responded by preparing type plans for each type of storage facility. These covered a variety of different types for structures. 1. General Storehouses. Large reinforced concrete

buildings were needed at all the main navy yards and

stations, and were provided at [in order of need] New

York, Boston, Philadelphia, Mare Island, Puget Sound,

New London, Hampton Roads, Charleston, Pearl Harbor,

Washington from 1917.

2. Fleet Supply Bases. Two fleet supply bases

were to be built - at Hampton Roads and New York. Both

required a wide variety of storage facilities. As space

was limited at New York Navy Yard, the fleet supply base

was built on a new site in South Brooklyn.

3. Temporary Stores $5.7m was appropriated in

1917 for the provision of timber storage buildings at

Norfolk, Philadelphia, New York and Hampton Roads.

A total of $30m was spent on 30 permanent and over 100 temporary facilities. A table on pp 327-328 lists the locations of 26 of the former [the other 4?]. They were at: Boston 2

New London 1 New York 1 Brooklyn 5 Philadelphia 5 Washington 1 Hampton 5 Charleston 1 Mare Island 2 Puget Sound 1 Annapolis 1 Pearl Harbor 1 This chapter does not cover storage for ordnance, ammunition, fuel [except emergency stores], oil fuel, and medical supplies. It does provide many plans and photographs of the whole range of buildings. It also provides information on more specialist storage facilities: Boat stores, at

Philadelphia and Mare Island

Airplane stores, at Philadelphia, Brooklyn and Hampton Roads Metal store, at Boston Lumber stores Freight sheds and piers - including the $12m facility at South Brooklyn Emergency coal stores, at Constable Hook NJ, Boston and Charleston Bunkering plants, at Hampton Roads, Newport News and Hoboken. CHAPTER

XV: STORAGE OF FUEL OIL

Prior to the war, the General Board had expressed concern about an adequate strategic reserve of fuel oil. As a result a program to expand or development new facilities was begun. This program continued during the war years but was not given a high priority. Storage areas which contained large concrete storage tanks were built at: 1. Guantanamo Bay, Cuba,

capacity 6 million gallons

2. Melville, RI, capacity 5 million gallons 3. Puget Sound, capacity 9.8 million gallons 4. San Diego, capacity 2.1 million gallons The largest and newest project was at: Yorktown, VA, capacity 30

million gallons

Some use was made of steel tanks as well as the main

requirement for concrete.The most immediate concern of the Bureau was to respond to a request from Admiral Sims in London to provide oil storage facilities in France. This was accomplished by the transfer of materials and equipment from the United States. 3 large 7,000 ton steel

tanks were dismantled at Norfolk, taken in sections to

Philadelphia, and from there, shipped to Brest. They

were re-erected and formed the main fuel storage

facility for US warships based in France.

9 new 3,000 ton steel tanks were built in sections and shipped to add capacity to French storage units at Furt, La Pallice and L'Orient. In addition to the tanks, pumps and piping were shipped to France. This chapter contains a lengthy personal memoir of the construction period at Brest by Lt. C. P. Conrad, Corps of Civil Engineers. CHAPTER

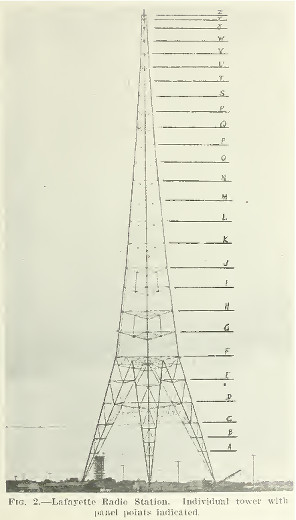

XVI: RADIO STATIONS

One of the eight 820ft radio masts erected near Bordeaux, France (panel points indicated on right - no enlargement) The design, testing and operation of radio stations was the responsibility of the Bureau of Engineering. The Bureau of Yards and Docks provided the supporting infrastructure - self-supporting towers, masts, operating buildings, power houses, quarters, barracks, water and sewerage, lighting and fencing. Three new high-powered radio stations were commissioned in the spring of 1917: San Diego, Cavite, and

Pearl Harbor.

Each with three 600 foot towers. Two more were constructed in the USA during the war: Cayey, Porto Rico - again

with three 600 foot towers.

Greenbury Point, Annapolis - which became the second most powerful transmitter in the USA after that at New Brunswick, NJ. A major project was the construction of a radio station at Croix D'Hins, near Bordeaux in France to handle all transatlantic communications (image above). A lengthy memoir with diagrams and photographs is found at the end of this chapter, written by Commander F C Cooke, CEC. Smaller projects included: Two 200 foot masts at

Philadelphia Navy Yard

One 300 foot mast at Charleston Navy Yard Two 200 foot masts at St. Thomas, Virgin Islands Masts of unknown height at Port au Prince, Haiti, and Bar Harbor, Maine. The conversion of a light house to radio station on Navassa Island in the West Indies In addition, the bureau supplied twenty 200 foot and four 300 foot masts to the Cuban government. Before June 1915, very little consideration was given to the special berthing and support needs of submarines. In that month, a plan was drawn up for the creation of a number of self-supporting submarine bases. Working on the basis that the main tactical organisation of submarines would be a squadron of ten boats, the blueprint was for the construction of two piers about 250 ft apart with room for this number of submarines, and the squadron's tender. There would be a full range of supporting facilities for the maintenance and repair of the boats. In addition, proper accommodation would be provided for 80 officers and 600 enlisted men. In practice, this standard plan was modified because of the particular characteristics of each site. The first project was at Pearl Harbor. The plan was approved on May 18th, 1916. The site chosen, in March 1917, was at Quarry Point. More piers would be built but further apart from each other. The bureau's history does not indicate the extent to which this base was completed by the end of 1918. The current submarine base at New London was to enlarged. The work was authorised in March 1917 and a budget of $1.25m was allocated. Eight finger piers [each 275ft x 20ft] were constructed. New barracks were built to accommodate 500 each. The former marine barracks was enlarged to provide for a further 750 personnel. An entirely new submarine base was constructed at Coco Solo, in the Panama Canal Zone. Construction was authorised on May 25th 1917 with a budget of $741,025. With four piers, repair and maintenance facilities were provided for up to 20 submarines. An air station was constructed alongside the submarine base [see next chapter]. At Philadelphia Navy Yard, Pier D in the Back Basin was modified for submarine use. A plan for new bases on the west coast was finalised in January 1917 with sites selected at Ediz Hook, WA, Tongue Point, OR; and San Pedro, CA. The only site where work began was at Tongue Point, and that was not until 1920. In late 1917, an L-shaped pier was constructed at Mare Island for submarine support. A submarine base was included in the plans for the new fleet base at Hampton Roads. Situated in the far north-eastern corner of the site, the base would consist of an enclosed basin [1,100 x 1,200 ft], a pier [1,200 x 120 ft], and ten finger piers [330 x 18 ft]. This base could support a maximum of 31 boats. Consideration was given to the construction of a base at Key West, but no work was done by the time of the armistice. CHAPTER

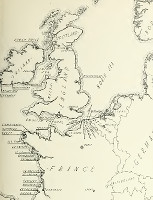

XVIII: SHORE FACILITIES FOR AVIATION

Before 1917 little thought was paid to the use of land bases for naval aircraft. The first land base was established at Pensacola, Fl. in 1914. This followed the use of temporary camps at Annapolis and Guantanamo Bay in 1913. By 1917, Pensacola had three seaplane hangers, and dirigible shed.] The first task of the bureau was to construct a series of patrol stations as bases for coastal patrol aircraft. As a result of investment in eight airship hangers, the following patrol stations were established during the course of 1917: Montauk, Bay Shore, and

Rockaway Beach on Long Island NY by the autumn of 1917.

Cape May NJ, was authorised August 16, 1917. Key West, Fl., Chatham, Cape Cod, and Hampton Roads followed late that month. Coco Solo, Panama Canal Zone, and San Diego by late 1917. Nine flying training stations were created during the war years. They were: Hampton Roads

Pensacola Santa Rosa, Fl. Charleston SC Great Lakes, Ill. Dunwoody Institute, Minneapolis Seattle San Diego Cambridge, Ma. Ten 'Rest Stations' were established. These would provide basic refuelling facilities for patrol aircaft. They were at: Waretown, NJ

Assateague, Va Beaufort, NC Charleston, SC Roanoke Island, NC St. Augustine, Fl. Tampa, Fl. Indian Pass, Fl. Isla Morada, Fl. Four permanent naval air stations were constructed: Marine Flying Field,

Quantico, Va

A fifth station was begun at Brunswick, Me. but

construction was abandoned after the armistice.Marine Flying Field, Parris Island, SC Naval Air Station, Yorktown, Va Naval Air Station, Galveston, Tx Major developments took place at the Naval Aircraft Factory, Philadelphia. Almost all the above were closed 1919-1920, and aviation facilities were reduced to two permanent stations: Pensacola, Fl. with 11

large and 8 small hangers.

San Diego, Ca, hangers for 20 seaplanes, 1 airship, and 2 kite balloons. A major part of the Bureau's work was the construction of air bases in Europe for use by the United States Navy. Up to March 1918, 6 were established in Ireland, 1 in England, and 18 in France. By the end of the war, a further 1 in England, 6 in France, 2 in Italy, and 1 in Tunisia were either completed or planned. A table on pages 419-420 gives full details, and a map is provided on page 421. The locations of air stations in Europe, and the function of each is listed below (* second wave): Ireland

Lough Foyle seaplane

Lough Swilly kite balloon Whiddy Island seaplane Berehaven kite balloon Queenstown repair base and seaplane Wexford seaplane England Killingholme seaplane

Eastleigh * assembly and repair France Dunkerque seaplane

Treguiler seaplane L'Abervrach seaplane Brest seaplane Brest kite balloon Guipavre dirigible Ile Tudy seaplane La Trinite kite ballooon La Croisie seaplane Palmbouef dirigible Fromentina seaplane La Pallice kite balloon Rochefort dirigible Saint Trojan seaplane Pauillac repairs Gujon dirigible Areachou seaplane Moutchic seaplane school Autingues * HQ northern bombing wing Campagne * seaplane Day Wing* HQ

Le Frene* seaplane Oye* seaplane St. Inglevert* seaplane Italy Lake Bolsena seaplane

TunisiaPescara seaplane Porto Corsini seaplane Bizerte proposed mine

base

All of the above were relinquished/abandoned after the armistice. CHAPTER

XIX: UNITED STATES HELIUM PRODUCTION PLANT, FORTH

WORTH, TEX.

The United States government responded to a request from Britain to develop a source of helium required for balloons. This could be accomplished by the construction of a plant which would extract helium from natural gas. A survey by the Bureau of Mines, led to the choice of a site in Texas known as the Petrolia [Texas] field. Three experimental plants were established from which the process developed by Linde Air Productions was chosen. The Bureau of Engineering designed the plant, and the Bureau of Yards and Docks constructed the plant on the northern outskirts of Fort Worth. Various types of specialised buildings and structures were built for tasks such as compression, separation, as well as boilers Much detail is given on the process of extraction at this point in the chapter. The new plant required the construction of a pipeline to carry the gas from the wells to the plant. The pipeline was over 100 miles long. Details are provided on pressure and capacity at this point in the account. The plant was connected to the electricity grid operated by Forth Worth Power and Lighting Co. The construction cost was $3.5m and it was capable of producing 40,000 cubic feet of helium per day. CHAPTER

XX: ACTIVITIES OF THE CORPS OF CIVIL ENGINEERS IN THE

WEST INDIES.

This chapter outlines activities which had no relation to the war effort. As a result of treaty obligations to Santo Domingo and Haiti, and to the new responsibility for the former Danish Virgin Islands, CEC officers were sent out to supervise a wide range of infrastructure projects in these three locations. In Santo Domingo, 2 CEC officers supervised a wide range of work including two main highways, railroads, bridges, water and sewerage facilities, the telephone network, schools, and harbor improvements. In Haiti. 8 CEC officers were employed on a similar wide range of tasks which included roads, public buildings, water supply, harbors and railroads. When the United States took over the administration of the Virgin Islands in February 1917, one CEC officer was tasked with a range of minor infrastructure projects. Given the scale of the task, progress was slow. CHAPTER

XXI: CONSTRUCTION DIVISION OF THE BUREAU

The main function of this division was to assess bids for work, and award contracts for that work. Between April 6th 1917 and November 11th 1918, the division directly awarded 841 project contracts, and approved 439 others which had originated locally in navy yards and elsewhere. A total of 1,016 contracts were awarded with a total expenditure of $120m. The award of a large number of other contracts were abandoned at the end of hostilities. This chapter offers a detailed account of how the financial aspects of contracts were assessed and negotiated. The process was flexible and changed during the months of the war. The division indicated the priority to be given to each contract. It developed an Information and Plans Section to oversee the progress of contracts; and employed a large number of locally enrolled inspectors to report on the progress of work. CHAPTER

XXII: MAINTENANCE AND OPERATIONS DIVISION OF THE

BUREAU

This division was created on March 26th, 1917. It had a

wide range of functions: some of which are described in

detail. They were:

1. Financial accounts and

records

2. Annual estimates 3. Navy Yard Personnel [Clerical & Technical] 4. Requisitions 5. Furniture records 6. Officers' Quarters 7. Navy Yard Transportation Facilities 8. Navy Yard Communications Systems 9. Public Works Date Book [Confidential] 10. Book of Yard Maps [Confidential] 11. List of Stations [Confidential] 12. Accounting systems at Navy Yards and job orders CHAPTER

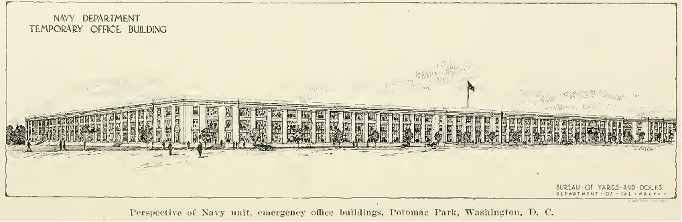

XXIII: EMERGENCY OFFICE BUILDING, POTOMAC PARK,

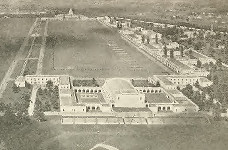

WASHINGTON

Navy Building, Washington DC (no enlargement) The inadequate size of the State, War and Navy Building was recognised before the war, but no action was taken until America's entry into the conflict. By July 1, 1917, the Navy Department occupied nine different buildings in various parts of the city. As the same problem affected the War Department, this department proposed the construction of a new building to house it, and some parts of the Navy Department. The Navy Department did not care for this arrangement, and proposed a separate building to house it on the one location. Ultimately, two separate buildings were built on the plot in Potomac Park - one to be named the Navy Building, and the other, the Munitions Building. The building was authorised on March 25th , 1918 - a month after the Bureau signed the contract. The cost would be $5,775,000. Contractors employed 3,400 men in the construction of reinforced concrete building which was completed on October 1st, 1918. The Navy Building had 940,000 square feet of office space, and the Munitions Building had 840,000 square feet. Much of this chapter is devoted to details of the design, and of the construction process. CHAPTER

XXIV: HOUSING FOR THE NAVY BY THE BUREAU OF INDUSTRIAL

HOUSING AND TRANSPORTATION, DEPARTMENT OF LABOR.

The outbreak of war, and the movement of workers to the many projects, created a severe shortage of housing in Washington DC and across the nation. On July 8th, 1918, President Wilson allocated $100m to provide a solution to the problem. The United States Housing Corporation was established. The Bureau worked closely with it to provide housing in and around naval bases and navy yards. Many of the housing projects were small scale. This chapter illustrates the nature and extent of the work by lengthy accounts of the work undertaken at a number of locations: Bridgeport, CT. Houses

for 889 families at a cost of $6m.

Hampton Roads, VA - 20,000 workers were employed on the site of the new operating base by January 1918. The housing requirement was set at 26,000 men at a cost of $10m. Three sites were chosen - Greenwood [which was abandoned 11.18]; Truxton [for 'colored' workers]; and Cradock [for white workers]. This chapter devotes a considerable amount of time to the work at Cradock where 198 detached and 26 semi-detached properties were built. It does not say anything about Truxton. Philadelphia PA - with 15,000 workers the bureau provided 650 houses Quincy, MA - with 16,000 works, a total of 424 family houses, and 21 dormitories were built. Vallejo, CA - 110 acres were developed for 95 houses, and 30 'flats' together with 10 dormitories. Bremerton - a memoir by one of the project managers is provided. Most of these properties were sold to private purchasers immediately after the war. On

that note the book comes to an end.

Graham Watson |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

return to World War 1, 1914-1918

|