|

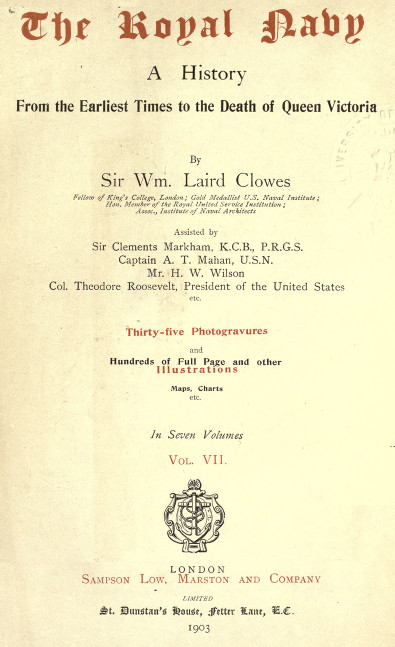

The frontispiece "Types of the Old Navy" (click to enlarge) |

on

to App to Ch 46, Flag Officers |

|

A Modern Introduction

Forget

your ideas about boring, dense, leather-bound Victorian

tomes. This one puts many modern books to shame with its

clear layout, excellent diagrams and tables, and its

readability. I wanted a good contemporary account of the

Navy in the second half of the 19th century and found

just that in Sir William Laird Clowes last volume. The

book covers so much that I decided to tackle one part at

a time, starting with the Introduction and the "Civil

History" of the Royal Navy.

I

had only heard about Clowes histories by reputation, but

it is certainly deserved. A measure of their importance

can be gained from the fact that two of his "Assistants"

were Capt Mahan, author of the famed "The Influence of

Sea Power upon History" and President Theodore Roosevelt

of the United States. As a comprehensive history of the

Royal Navy from the earliest times up to 1900, my hope

is to present all seven volumes in the manner here,

which includes additional images to assist the visitor.

In reading the technical accounts it is important to note that all the industrial/maritime powers took part in the development of warship technology. Indeed there were times when the Royal Navy lagged behind. For example, Clowes refers to 1885 when the Royal Navy, still mainly equipped with muzzle-loading guns could have found itself in battle with a Russian fleet of breech-loaders.

So many characteristics of the Royal Navy we take for granted in the two World Wars and up to the present time can be traced back to this period, which in my opinion makes Clowes' work even more important.

With thanks to Digital Book Index for making this resource available, and also to those internet sites from which the additional images come. Unless otherwise identified, they are from the excellent "Photo Ships".

The

three chapters and three appendices in VOLUME 7 are in

six separate files with links in the Contents List. I

have taken the liberty of replacing the Roman numerals

used for Volumes, Chapters and Appendices to hopefully

make it easier to follow the contents.

Any

transcription and proofing errors are mine.

Gordon Smith, Naval-History.Net |

Chapter

46 only |

|

Note:

Most of the images are from the original. The ship

images are mainly from Photo Ships. Those that are

not, are identified. My thanks to these sites.

|

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

46.

CIVIL

HISTORY OF THE ROYAL NAVY, 1857-1900 ... 1

By Sir Wm. Laird Clowes.

Page

(sometimes added Section) Headings

Organisation

and Administration:

Admiralty Officials

Superintendents of Dockyards

Reorganisation of the Admiralty

Constitution of the Admiralty

Strength of the Officers' List

Changes in Officers' Rank

Pay and Wages

Naval Reserves

Warships:

The First Ironclads

Iron as a Building Material

Experimental Types of Fighting Ships

Sea-Going Turret Ships

The Forces of Evolution

Transitional Types of Fighting Ships

The Standard Type of Battleship

The "Formidable" Class

Gun-Vessels and Gun-Boats

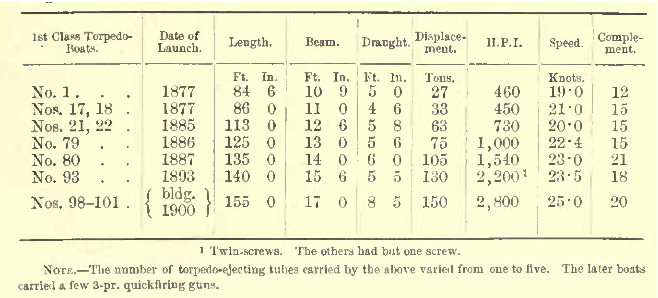

Torpedo Boats

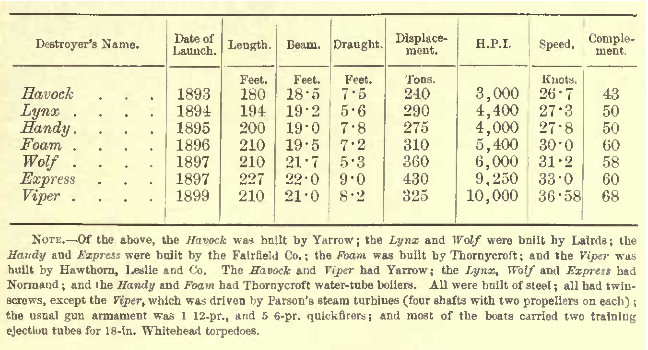

Destroyers and Special Service Craft

Weapons and

Technical

The Earliest Breechloaders

Reversion to the Muzzle-Loader

Woolwich-Armstrong Breechloaders

Quick-Firing Guns

Gunnery

Screws

Boilers

The Development of Armour

The Whitehead Torpedo

Submarine Boats

Masts and Sails

Signalling

Personnel

and General

Health

of the Navy

Scientific Training

Training of Reserves

The Royal Marines

Naval Clubs

Influence on Foreign Navies

The Character of the Bluejacket

Popular Interest in the Navy

Naval Reviews

Appendix to Chapter 46. (link to different file):

Flag-Officers

Holding the Principal Commands, 1857-1900 ... 85

CHAPTER 47.

(in preparation)

MILITARY HISTORY

OF THE ROYAL NAVY, 1857-1900 ... 91

By Sir Wm. Laird

Clowes.

CHAPTER

48

(link to different file)

VOYAGES AND DISCOVERIES, 1857-1900 ... 562

By Sir Clements E. Markam, K.C.B., P.R.G.S.

Appendix A to Chapters 46-48: (link to different file)

List of Flag-Officers Promoted 1857-1900 ... 569

Appendix B to Chapters 46-48: (in preparation)

List of H.M.

Ships Lost, Etc., 1857-1900 ... 582

INDEX

(not included)

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

in

Chapter 46 only

VOLUME 7.

Photogravure

Plates.

Full-Page

Illustrations

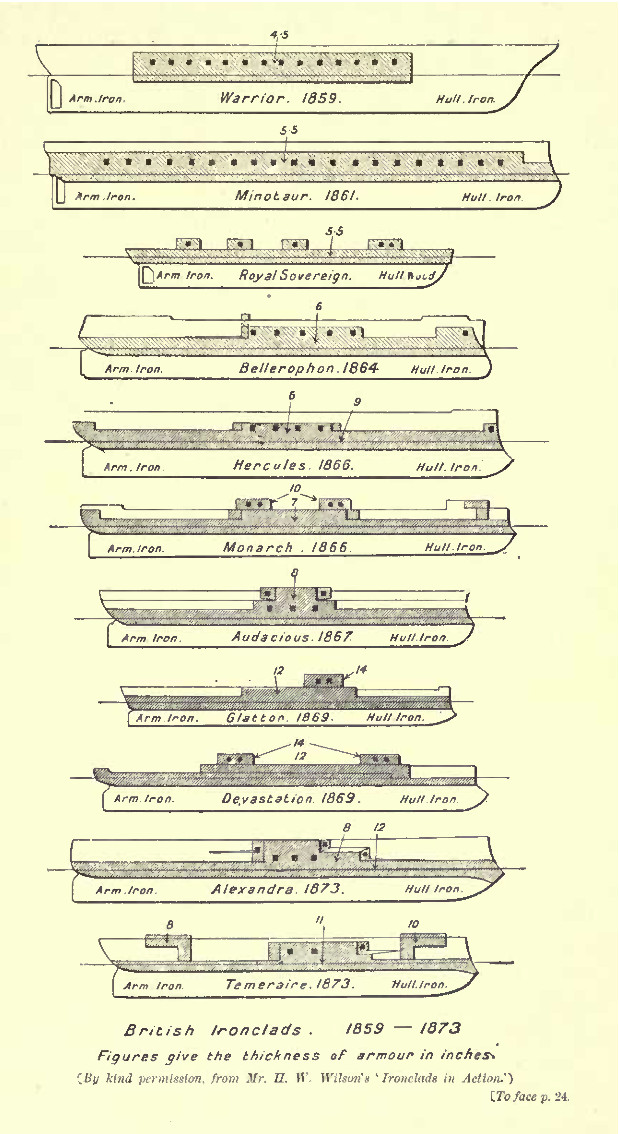

Armour of British Ironclads, 1859-73 ... 24

H.M.S. "Glory," 1899 ... 34

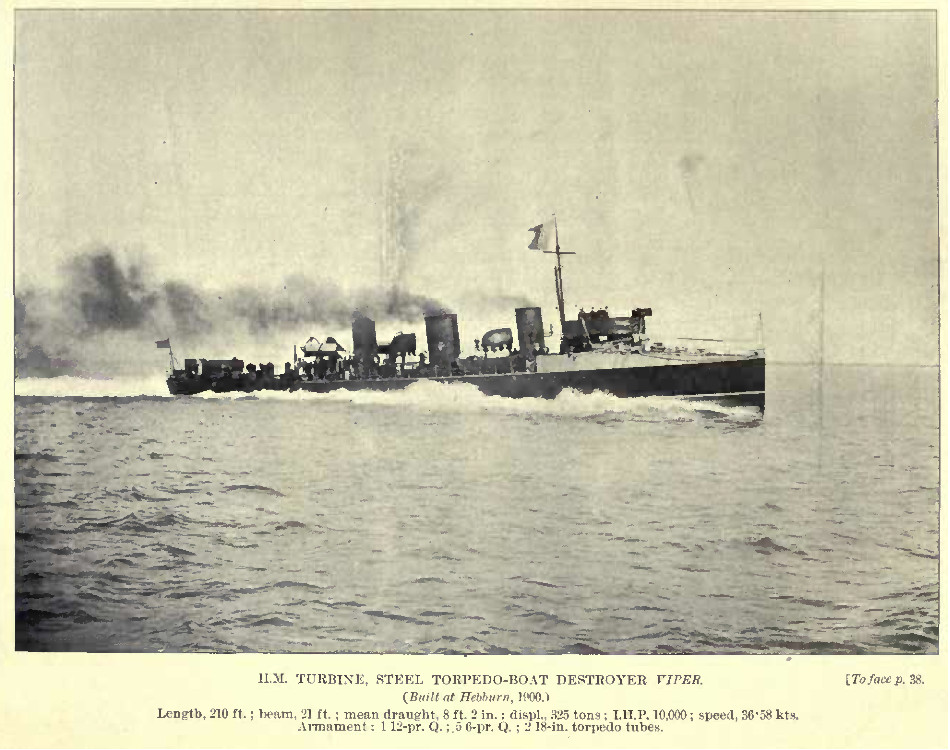

H.M.S. "Viper," 1900 ... 38

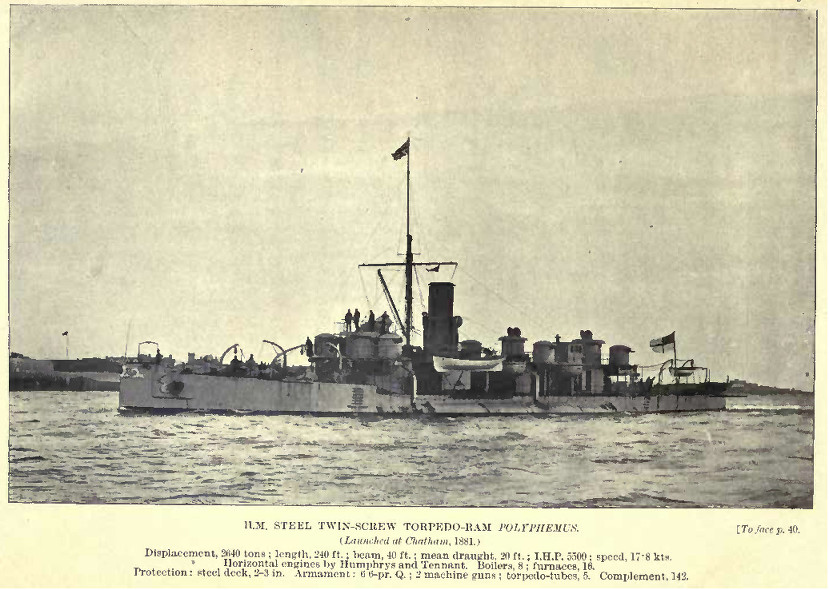

H.M.S. "Polyphemus," 1881 ... 40

H.M.S. "Vulcan," 1889 ... 42

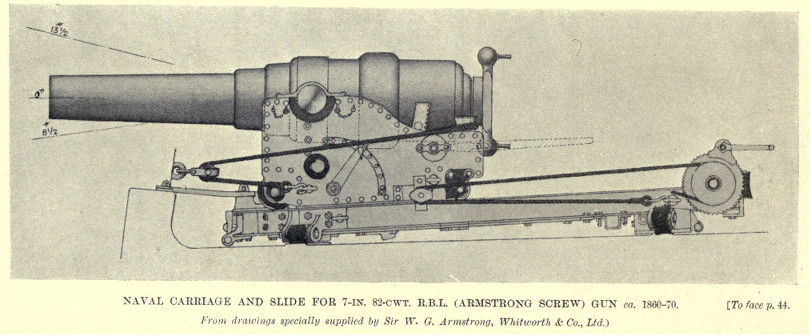

Naval Carriage and Slide For 7-in. R.B.L. Gun, 1860-70 ... 44

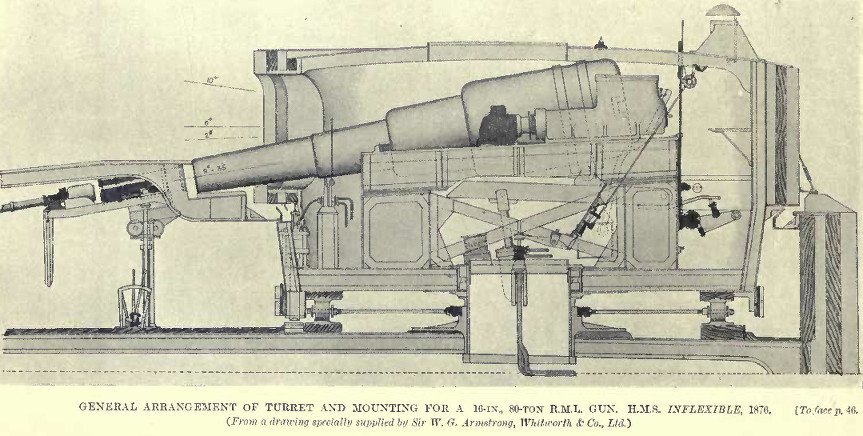

Turret and Mounting for a 16-in. 80-Ton R.M.L. Gun, 1876 ... 46

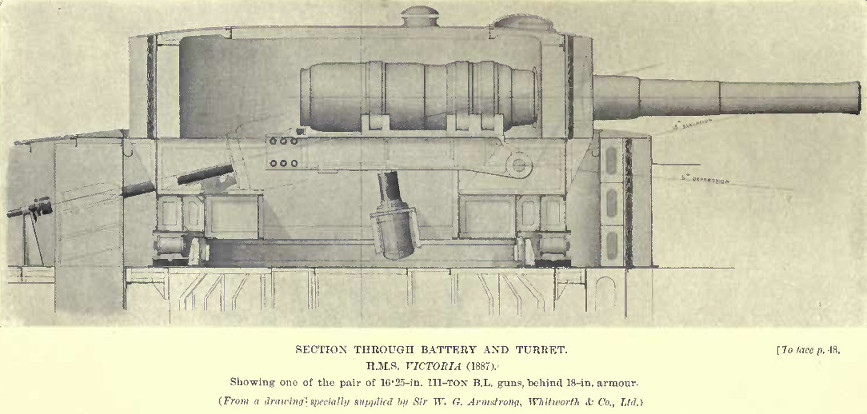

Section Through Turret of H.M.S. "Victoria," 1887 ... 48

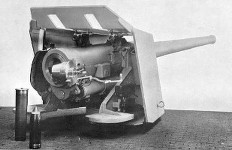

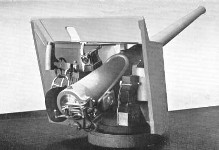

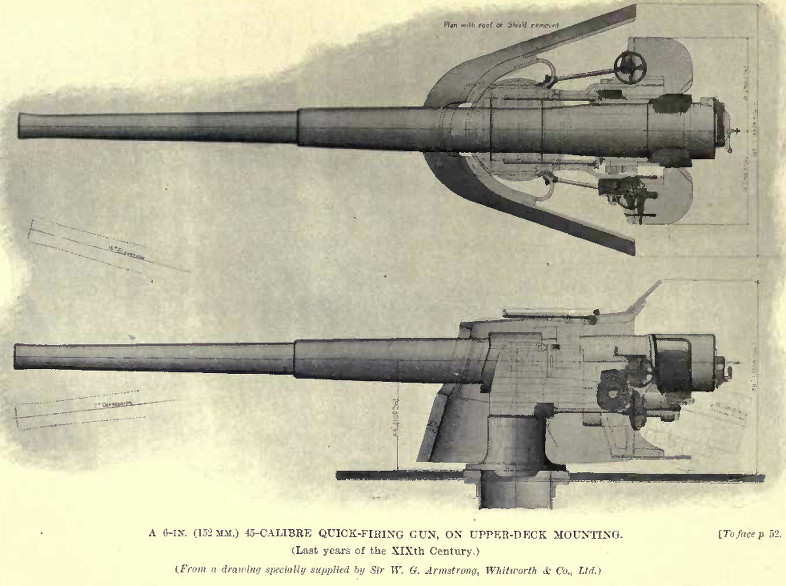

A 4.7-in. Gun on Centre-Pivot Mounting ... 50

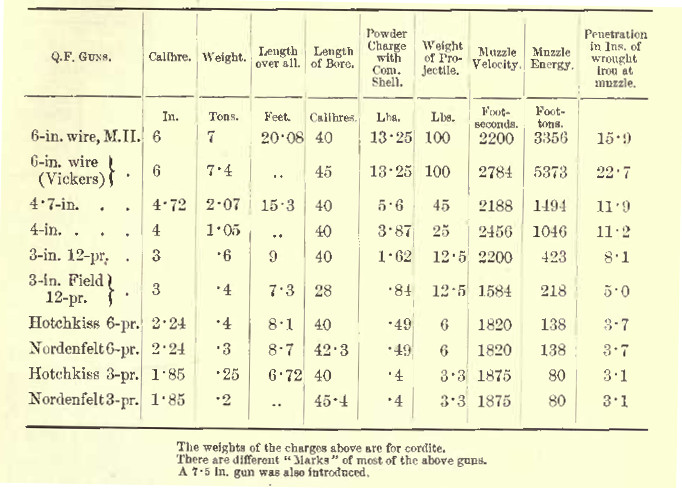

A 6-in. 45-Cal. Q.F. Gun on Upper-Deck Mounting ... 52

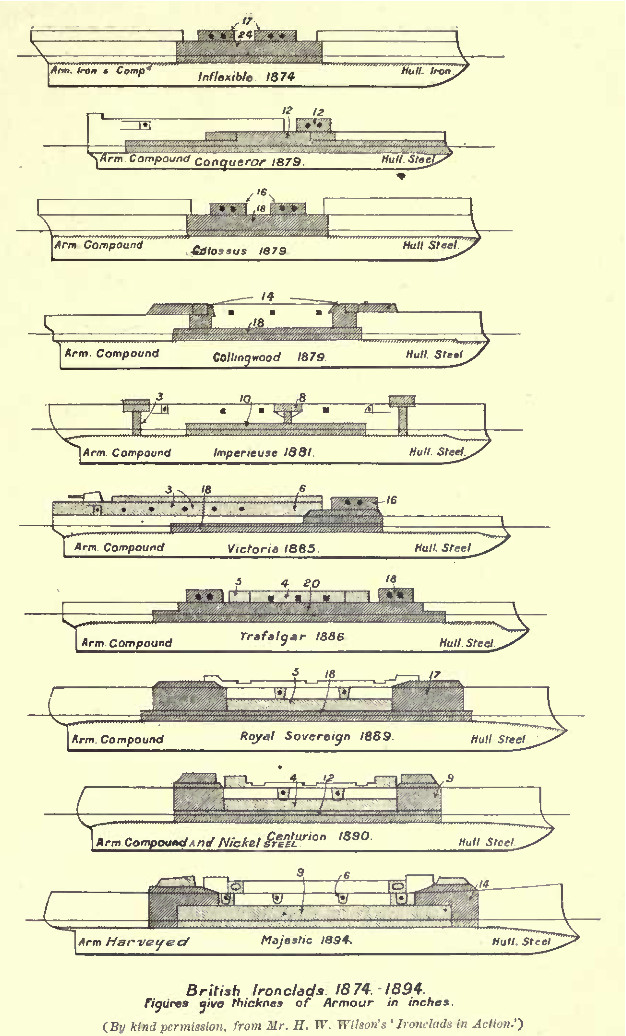

Armour of British Ironclads, 1874-94 ... 56

Rear-Admiral H.R.H. Prince George of Wales ... 83

Illustrations

In The Text

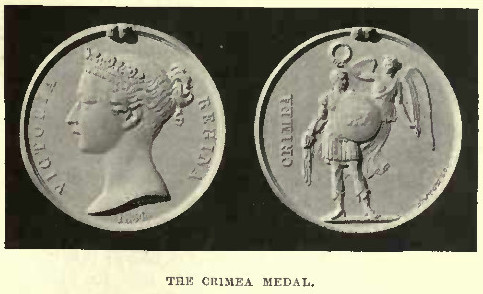

The Rt. Hon. George Joachim, 1st Viscount Goschen ... 9

Signature of Sir Edward James Reed, K.C.B., F.R.S. ... 10

Signature of Sir Nathaniel Barnaby, K.C.B. ... 10

H.M.S. "Royal Sovereign," 1857-64 ... 22

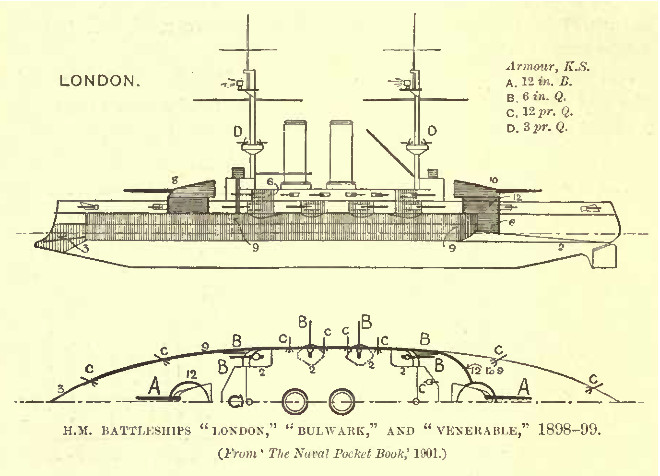

Plan of H.M.S. "London" ... 34

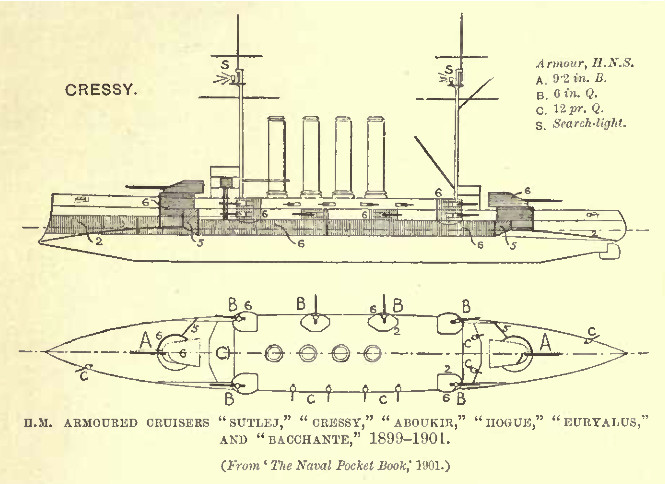

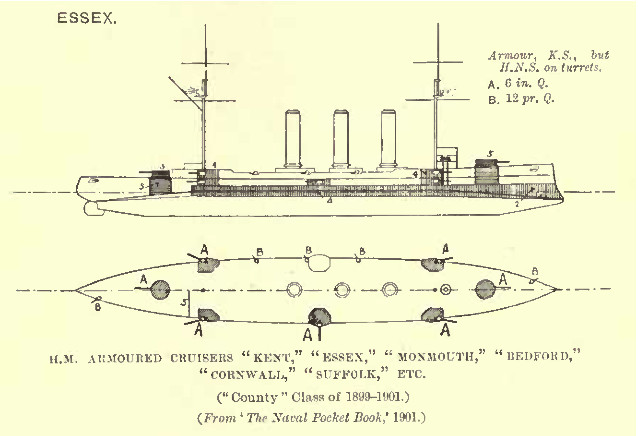

Plan of H.M.S. " Essex" ... 35

Plan of H.M.S. "Cressy" ... 37

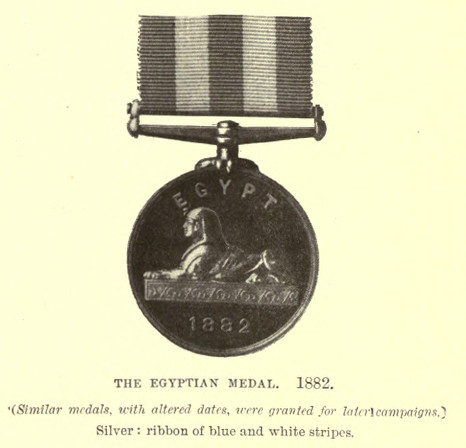

Egyptian Medal, 1882 ... 84

INTRODUCTION

TO VOLUME 7.

THE present volume completes the History of

the Royal Navy from the earliest times down to the date of the

death of her late Majesty, Queen Victoria, at the beginning of

the year 1901. Publication of the work, which, it was

originally intended, should be finished in about three years

and a half, counting from the summer of 1896, has

unfortunately occupied instead a period of nearly seven years;

and I fear that the unpremeditated delay in the appearance of

volume after volume has been not only a disappointment to many

people who have been good enough to take a lively interest in

the progress of the work, but also a source of great

additional expense to my most courteous and considerate

publishers.

Begun at a time when I was in my usual good

health, Volume I. was still in the rough when I was attacked

by a malady, which, though its action is sometimes slow,

seldom spares the life of its victim; and, in consequence, I

was suddenly ordered away from England, where alone I could

have prosecuted the work under conditions entirely favourable.

Except during brief intervals, I had to remain abroad or in

the Channel Islands until the autumn of 1902. These facts

account for some part of the delay.

Another part is to be accounted for by a

determination, arrived at about the year 1898, that the book

should consist of a larger number of volumes than had been

originally contemplated. The number first fixed upon had been

five: it grew to six, and then to seven. I do not think that

this extension of scope is, upon the whole, to be regretted,

although undoubtedly it postponed the publication of the final

volume for more than two years. It has enabled a more liberal

allowance of space than otherwise would

INTRODUCTION

TO VOLUME 7.

have been available to be devoted to an account of the marvellous material changes which revolutionised naval warfare in the last half of the nineteenth century, and it afforded room for the inclusion of what I trust, will be found to be a sufficiently full history the Navy's share in the important operations in South Africa and China in the closing days of the Victorian era. The lamented death of the great Queen, at the very threshold of a new century immediately after success had been secured in China and assured in South Africa, furnished me with a date obviously suitable, in every respect, at which to bring my task to a halt.

I do not wish to insist too strongly upon

the disadvantages under which, as I have explained, I laboured

almost from the commencement: but it is necessary that I

should ask that any unfavourable sentence which may be passed

upon my work shall be mitigated in consideration of the

hostile circumstances in which I have been obliged to perform

it. I know, far better than anyone who may be my critic, the

numerous shortcomings of these seven volumes. I know, too, how

much fewer those shortcomings would have been, if I had had

good health instead of bad, throughout these seven years.

Excellent searchers, and other

fellow-workers have aided me from the beginning to the utmost

of their power; yet I would have preferred to do for myself

what they have done me; and, had I been in a position to do

so, the results would have been more satisfactory, certainly

to myself, possibly also to the reader; for it hardly needs

saying that notes and documents in one's own handwriting are

less likely to be misunderstood, mis-transcribed in quotation,

and misapplied, than notes and documents copied in a score of

different writings, not all of which are equally legible.

Nevertheless, thanks to the large revision which most of the

history of the events of the second half of the last century

has undergone at the kind hands of those who took personal

part in them, I have reason to hope that, upon the whole, the

contents of this volume are very trustworthy records or the

facts.

During the long and interesting period covered by this final instalment of the work, Great Britain was engaged in no purely maritime war of any importance. She was not called upon to fight one considerable action in the open sea; and such bombardments as her ships were concerned in were far less serious matters than the bombardment of Copenhagen, in 1801, or even the naval attack upon Sebastopol in 1854.

INTRODUCTION TO

VOLUME 7.

Yet at no period has the British Navy been

more continuously engaged, or more widely employed, in small

wars, and in those too soon forgotten police duties, which

confer so many benefits upon the Empire, and often lack,

nevertheless, any chronicler other than the officer who

reports them dryly to the Admiralty. Some hundreds of these

minor operations will be found described in the present

volume; and few readers, I suspect, will fail to be surprised

at the number of them. They give one a new idea of the

wakefulness and ubiquity of the Empire's maritime forces. Here

a rebel tribe is chastised; there a consul is protected and

vindicated; elsewhere a slaver is captured and her cargo of

slaves set at liberty; and much of this is done without the

great public hearing a word about it at the time. The extent

and usefulness of this quiet work of the Navy is one of the

characteristics of the period under review.

Another is the frequency, previously

unparalleled, with which the officers and men of the service,

either with troops or alone, have been employed to do what

should be purely landsmen's work, all over both hemispheres,

sometimes fighting hundreds of miles from the sea. I venture

to think that this employment of them has tended of late to

become far too common. The naval officer and the bluejacket

are expensive servants of His Majesty. They cannot be trained

or replaced quickly, and they are entered and educated for

another object. When a ship disembarks and sends up-country a

large contingent of her people, and possibly also a number of

her guns, she reduces her own usefulness, perhaps to vanishing

point; and, on certain stations, it might be an extremely

serious matter if, in the event of a large man-of-war being

suddenly required to cope with an emergency, she could neither

move nor fight.

One can hardly resist the conclusion that

if the army, regular and irregular, were formed, organised,

armed, and stationed as it should be, the calls for the

assistance of the Navy on shore would be fewer. It is,

however, a subject for congratulation that the Navy, when thus

summoned, has never failed to respond in the handsomest and

noblest manner; and that, whether working single-handed or

with the army, alike in New Zealand, in India, in the Soudan,

in South Africa, and in China, it has gathered to itself fresh

laurels.

INTRODUCTION

TO VOLUME 7.

The Royal Marines, of course, are properly

enough regarded as an amphibious corps; yet the manner in

which, on at least one occasion, they were employed in South

Africa suggests that those generals who recollected that the

Marines are soldiers may have forgotten that they are also

part of every efficient British man-of-war's complement. Even

more than the seamen, if that be possible, have the Royal

Marines added, since 1856, to their magnificent reputation.

Yet another characteristic of the period -

and I greet it as a happy omen is the increasing frequency

with which the officers and bluejackets of the United

States of America have found themselves ranged side

by side with their cousins of the British Navy. In the Pei-ho,

in Japan, in Central America, in the far North-West, on the

Atlantic during the laying of the early cables, in Egypt, in

Chile, in Samoa, and, more recently, in China, American seamen

and marines have been the loyal comrades of British ones; nor,

I believe, has any unpleasantness, jealousy, or friction ever

arisen when men of both nations have served together, as has

often happened, under the leadership and command of a single

officer, British or American.

The naval services of the two

English-speaking nations have shown their trust in, and

sympathy with, one another so repeatedly, and have so often

cemented their good feeling with the shedding of blood and the

sacrifice of gallant life, that one is entitled to hope that

never in the future will the relations between them be less

frank and cordial, and that the general body of the people of

the two countries will soon learn to look towards one another

as generously and confidently as the two navies do already.

Britain and America, acting together, should always be able to

ensure the peace of the world. Their action on opposite sides

would be the greatest catastrophe that could possibly happen

to the interests of civilisation, freedom, and progress.

To name here all those who have encouraged and assisted me in the final stage of my long task would be impossible. His most gracious Majesty has been pleased to show his personal interest in the undertaking by conferring upon me an honour which only his kindness could have deemed me deserving of. From Viscount Goschen, the late, and the Earl of Selborne, the present, First Lord of the Admiralty, I have received help for which I cannot too fully express my gratitude. To the Foreign Office also I am much indebted. The authorities of the British Museum Library, and the Library of the Patent Office, as usual, have given ready help to my assistants; and Sir William Howard Russell has facilitated their researches in certain directions by placing at their disposal, and allowing to be removed from his office, his own file of the Army and Navy Gazette.

INTRODUCTION TO VOLUME 7.

To Mr. A. F. Yarrow, the well-known builder

of fast small craft, I am deeply obliged for the personal

interest which he has taken in .the completion of the work,

and for the sympathetic manner in which he has aided me.

To mention the naval officers who have

furnished me with facts and suggestions would almost involve

the transcription to these pages of the entire list of living

and lately living flag-officers and captains. It has been my

aim, whenever possible, to secure personal narratives, in the

shape of letters, diaries, and private journals, wherewith to

supplement the information, often very meagre and defective,

contained in official despatches: and my efforts in that

direction have brought me into correspondence, during the past

ten years, with no fewer than 741 naval and Marine officers,

who, nearly without exception, have taken much trouble on my

behalf, and have generously placed at my disposal everything

in their possession that could be of use to me. Many valuable

facts relating to the work of the Royal Marines have been

brought to my notice, thanks to the courtesy of the officers

editing the Globe and Laurel, the admirable journal of that

distinguished corps.

Of officers who, though not in the Navy,

were associated intimately with duties in which the Navy was

employed, no one showed me greater kindness, or took more

pains to be of real service to me than the late General Sir

Andrew Clarke.

To Miss E. M. Samson, who has again

undertaken the difficult business of providing the index, I

tender my grateful thanks. To my publishers, Messrs. Sampson

Low, Marston & Co., Ltd., and, in particular to Mr. E.

Marston and to his son, Mr. E. B. Marston, members of the

Directorate, I owe more gratitude than I can express for the

generous and cheerful way in which they have borne with the

numerous disappointments and annoyances incidental to the

association with them in a great and costly undertaking of one

who too frequently has been incapable, for weeks at a time, of

carrying out the letter of his agreements with them. The

kindly allowances which Mr. R. B. Marston, with whom I chiefly

corresponded, was ever willing to make, and the thoughtful way

in which he ever considered my health rather than his

convenience, will never be forgotten by me. If this History,

as I hope it may, be welcomed as a chronicle of affairs which

hitherto have never been chronicled

INTRODUCTION

TO VOLUME 7.

together in a single, work; if it aid, as I

trust it will, in strengthening my countrymen for many a year

to come in their determination that the British Navy shall be

second to none in the world; and if, in the future, the long

story which is told in it shall contribute aught to the

encouragement of Britons who are inclined to despair, or to

the ardour of those who believe in the glorious destinies of

their race, then let the credit be given to the Messrs.

Marston, but for whose patriotic co-operation it could not

have been offered to the public.

WM. LAIRD

CLOWES.

April, 1903.

1

CHAPTER

46

CIVIL

HISTORY OF THE ROYAL NAVY, 1857-1900.

Administrative

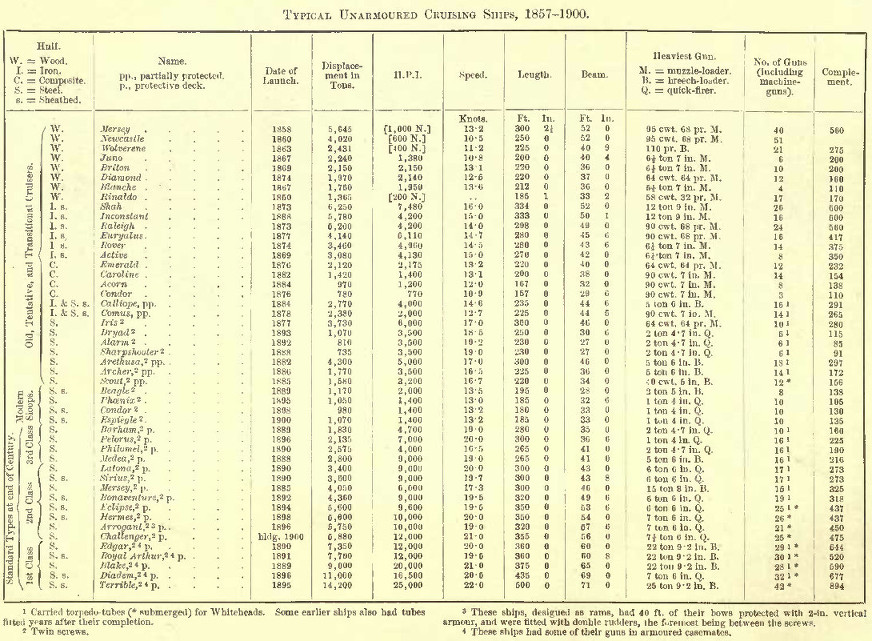

Officials at the Admiralty and the Dockyards - Changes at the

Admiralty - Division of Admiralty Work - The Navy Estimates -

Alterations in the Active List - Admirals of the Fleet -

Flag-Officers - Ensigns - The Navigating Branch - New Ranks -

Retirement - Pay - Wages - Naval Reserves - Naval Architecture -

Ironclads - Experimental Types - New factors in Naval Warfare -

Armoured Cruisers - Unarmoured Cruisers - Gunboats -

Torpedo-boats - Torpedo-boat Catchers - Destroyers - Miscellaneous

Craft - Yachts - Mercantile Auxiliaries - Ordnance - The first

Breech-loaders - Improved Muzzle-loaders - The later

Breech-loaders - Quick-firing Guns - Small Arms - Machine-guns -

Gunnery - Engines and Boilers - Screws - Turbines - Water-tube

Boilers - Armour - Projectiles - Torpedoes - Torpedo-nets -

Submarine Boats - Illumination - Electricity - Masts and Sails -

Conning-towers - Signalling - Uniform - Health of the Navy -

Training and Technical Education - The Britannia - Gunnery and

Torpedo Schools - Training-ships - Technical Schools - Guardships

- Royal United Service Institution - Miscellaneous Innovations -

Orders and Medals - Naval Clubs - Influence of the British Navy on

Foreign Services - Attaches - The Naval Intelligence Department -

The Bluejacket - Sailors' Homes - Royal Naval Fund - Influence of

popular Interest in the Navy - Naval Reviews - The Royal Naval

Exhibition - The Navy League - The Navy Records Society - The

Jubilee Reviews.

2 CIVIL HISTORY OF THE ROYAL NAVY, 1857-1900.

pages 2-8

ADMIRALTY OFFICIALS

Feb. 25, 1858, Earl of Derby;

June 18, 1859, Lord Palmerston;

Nov. 6, 1865, Earl Russell;

July 6, 1866, Earl of Derby;

Feb. 27, 1868, Mr. Disraeli;

Dec. 9, 1868, Mr. Gladstone;

Feb. 21, 1874, Mr. Disraeli (Earl of Beaconsfield, 1876);

Apr. 28, 1880, Mr. Gladstone;

June 24, 1885, Marquess of Salisbury;

Feb. 6, 1886, Mr. Gladstone;

Aug. 3, 1886, Marquess of Salisbury;

Aug. 18, 1892, Mr. Gladstone;

Mar, 3, 1894, Earl of Rosebery;

July 2, 1895, Marquess of Salisbury (again 1900).

FIRST LORDS OF

THE ADMIRALTY.

Mar. 8, 1858. Rt. Hon. Sir John Somerset Pakington, Bart., M.P. (G.C.B. 1859).

June 28, 1859. Edward Adolphus, 12th Duke of Somerset, K.G.

July 13, 1866. Rt. Hon. Sir John Somerset Pakington, Bart., G.C.B., M.P.

Mar. 8, 1867. Rt. Hon. Henry Thomas Lowry Corry, M.P.

Dec. 18, 1868. Rt. Hon. Hugh Culling Eardley Childers, M.P.

Mar. 13, 1871. Rt. Hon. George Joachim Goschen, M.P.

Mar. 6, 1874. Rt. Hon. George Ward Hunt, M.P.

Aug. 15, 1877. Rt. Hon. William Henry Smith, M.P.

May 13, 1880. Thomas George, 1st Earl of Northbrook, G.C.S.I.

July 2, 1885. Rt. Hon. Lord George Francis Hamilton, M.P.

Feb. 16, 1886. George Frederick Samuel, 1st Marquess of Ripon, G.C.S.I.

Aug. 6, 1886. Rt. Hon. Lord George Francis Hamilton, M.P.

Aug. 23, 1892. John Poyntz, 5th Earl Spencer, K.G.

July 4, 1895. Rt. Hon. George Joachim Goschen, M.P.

Nov. 1900. William Waldegrave, 2nd Earl of Selborne.

SECRETARIES

OF THE ADMIRALTY.

FIRST SECRETARY.

Ralph Bernal

Osborne, M.P.

Mar. 9, 1858. Rt. Hon. Henry Thomas Lowry Corry, M.P.

June 30, 1859. Lord Clarence Edward Paget, C.B., M.P., R.-Adm. (V.-Adm. 1865).

Apr.

30, 1866. Hon. Thomas George Baring, M.P. (Lord Northbrook,

1866).

July 16, 1866. Lord

Henry Charles George Gordon-Lennox, M.P.

Dec. 18, 1868. William Edward Baxter, M.P.

(Title changed to that of Parliamentary Secretary, 1870.)

SECOND SECRETARY

Thomas Phinn.

May

7, 1857. William Govett Romaine, C.B.

June 29, 1869. Vernon Lushington, Q.C.

(Title changed to that of Permanent Secretary, 1870.)

PARLIAMENTARY SECRETARY.

July 12, 1870. William Edward Baxter, M.P.

Mar. 6, 1874. Hon. Algernon Fulke Egerton, M.P.

May 15, 1880. Rt. Hon. George John Shaw-Lefevre, M.P.

Dec. 1, 1880. George Otto Trevelyan, M.P.

May 13, 1882. Henry Campbell-Bannerman, M.P.

Nov. 20, 1884. Sir Thomas Brassey, K.C.B., M.P.

July 3, 1885. Charles Thomson Ritchie, M.P.

Feb. 16, 1886. Rt. Hon. John Tomlinson Hibbert, M.P.

Aug. 6, 1886. Arthur Bower Forwood, M.P.

Aug. 24, 1892. Rt. Hon. Sir Ughtred James Kay-Shuttleworth, Bart., M.P.

July 4, 1895. William Grey Ellison-Macartney, M.P.

Nov. 1900. Hugh Oakeley Arnold-Forster, M.P.

upon the abolition of the office of Naval Secretary.)

May 15, 1882. Robert Hall (3), C.B., retd. V.-Adm., (actg.), (died June 11, 1882).

June 13, 1882. George Tryon, C.B., Capt., R.N. (actg.).

May 3, 1883. George Tryon, C.B., Capt., R.N.

Apr. 2, 1884. Evan Macgregor, C.B. (K.C.B., 1892).

Feb. 7, 1861. Robert Spencer Robinson, 1 R.-Adm.(V.-Adm.l866, K.C.B. 1868).

Feb. 14, 1871. Robert Hall (3), 1 C.B., Capt., R.N.

Apr. 29, 1872. William Houston Stewart, C.B., R.-Adm. (V.-Adm. 1876; K.C.B. 1877: Adm. 1881).

Dec. 1, 1881. Thomas Brandreth, R.- Adm. 1 (V.-Adm. 1884).

Nov. 28, 1885. William Graham, C.B., V.-Adm. 1 (K. C. B., 1887).

Aug. 6, 1888. John Ommanney Hopkins, R.-Adm. 1 (V.- Adm. 1891).

Feb. 2, 1892. John Arbuthnot Fisher, C.B., R.-Adm. 1 (K.C.B., 1894: V.-Adm. 1896).

Aug. 24, 1897. Arthur Knyvet Wilson, C.B., V.C., R.-Adm.1

May 10, 1858. Charles Richards, Paym., R.N. 2

Feb. 1, 1886. Henry Francis Redhead Yorke (late R.N.), (C.B. 1897).

DIRECTOR OF TRANSPORTS AND PRISONERS OF WAR.

Feb. 21, 1855.

William Drew.

(In

1857 the duties of this office were added to those of the

Controller of the Victualling;

but

the services were again separated in 1862.)

DIRECTOR OF

TRANSPORTS.

Apr. 30, 1862.

William Robert Mends, C.B., Capt. R.N. (retd. R.-Adm. 1868;

K.C.B.; retd. V.-Adm. 1874; retd. Adm., 1879; G.C.B. 1882).

Apr. 1, 1883. Sir

Francis William Sullivan, K.C.B., C.M.G., R.-Adm. (V.-Adm.

1885).

Aag. 20, 1888.

Harry Woodfall Brent, Capt., R.N. (retd. 1889; retd. R.-Adm.

1890).

Aug. 20, 1896.

Bouverie Francis Clark, Capt., R.N. (retd. 1897; retd. R.-Adm.,

1899.)

STOREKEEPER-GENERAL.

Hon. Robert

Dundas.

(Title

changed in 1869 to that of Superintendent of Stores.)

SUPERINTENDENT OF

STORES.

Apr. 13, 1869.

Nelson Girdlestone.

Jan. 23, 1872.

Coghlan McLean Hardy.

(Title

changed in 1876 to that of Director of Stores.)

DIRECTOR OF

STORES.

1876. Coghlan

McLean Hardy.

Apr. 1, 1889.

William George Front Gilbert.

Apr. 1, 1895.

Gordon William Miller.

HYDROGRAPHER.

John Washington,

Capt., R.N.

Sept. 19, 1863.

George Henry Richards, Capt., R.N. (R.-Adm. 1870; C.B. 1871;

retd. R.-Adm., Jan. 19, 1874).

Feb. 3, 1874.

Frederick John O. Evans, C.B., retd. Capt., R.N. (later K.C.B.)

Aug. 1, 1884.

William James Lloyd Wharton, Capt,, R.N. (retd. 1891; retd.

R.-Adm. 1895; C.B. 1895; K.C.B., 1897).

CHIEF

CONSTRUCTOR.

Isaac Watts (C.B.

1862).

July 9,1863.

Edward James Reed (C.B., 1868, K.C.B., 1880).

Resigned

July 8, 1870, whereupon the office was left open until:

Aug. 17, 1872.

Nathaniel Barnaby (C.B., 1876; K.C.B., 1885.)

(Title

changed in 1875 to that of Director of Naval Construction.)

DIRECTOR OF NAVAL

CONSTRUCTION.

1875. Nathaniel

Barnaby.

Oct. 1, 1885.

William Henry White.

(Title

of Assistant Controller added Dec. 17, 1885.)

ASSISTANT

CONTROLLER AND DIRECTOR OF NAVAL CONSTRUCTION.

Dec. 17, 1885.

William Henry White (C.B. 1891; K.C.B. 1895).

CHIEF ENGINEER

AND INSPECTOR OF STEAM MACHINERY.

Thomas Lloyd.

(Title

abolished, Feb. 4, 1869.)

SURVEYOR OF

FACTORIES AND WORKSHOPS AND CONSULTING ENGINEER.

Jan. 19, 1869.

Andrew Murray.

(Title

abolished, Feb. 24, 1870.)

ENGINEER-ASSISTANT.

Oct. 20, 1860.

James Wright.

(

Title changed in 1872 to that of Engineer- in-Chief.)

ENGINEER-IN-CHIEF.

Aug. 17, 1872.

James Wright (C.B. 1880).

May 1, 1887.

Richard Sennett, Insp. of Mach., R.N.

May 6, 1889.

Albert John Durston, Insp. of Mach., R.N. (Chf. Insp. of Mach.

1893; C.B. 1895; K.C.B. 1897).

ACCOUNTANT-GENERAL

OF THE NAVY.

Sir Richard Madox

Bromley, K.C.B.

Apr. 1, 1863.

James Beeby.

Oct. 31, 1872.

Henry William Routledge Walker.

June 1, 1878.

Robert George Crookshank Hamilton.

May 8,1882.

William Willis (Kt. 1885).

June 1, 1885. Sir

Gerald Fitzgerald, K.C.M.G.

Dec. 1, 1896.

Richard Davis Awdry, C.B.

DIRECTOR-GENERAL

OF THE MEDICAL DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY.

Sir John Liddell,

M.D., F.R.S., R.N.

Jan. 21, 1864.

Alexander Bryson, C.B., M.D., R.N.

Apr. 15, 1869.

Alexander Armstrong, M.D., R.N. (K.C.B. 1874).

Feb. 1, 1880. John

Watt Reid, M.D., R.N. (K.C.B. 1882).

Feb. 27, 1888.

James Nicholas Dick, C.B., R.N. (K.C.B. 1895).

Apr. 1, 1898. Sir

Henry Frederick Nor- bury, M.D., K.C.B., R.N.

COMPTROLLER-GENERAL

OF THE COAST GUARD.

Charles Eden,

Commodore.

Aug. 3, 1859.

Hastings Reginald Yelverton, C.B., Commodore.

Apr. 27, 1863.

Alfred Phillipps Ryder, Commodore.

Apr. 9, 1866. John

Walter Tarleton, C.B. (R.-Adm. 1868).

(This

office was abolished in 1869.)

ADMIRAL

SUPERINTENDENT OF NAVAL RESERVES.

Jan. 1,1875. Sir

John Walter Tarleton, K.C.B., V.-Adm.

Nov. 13, 1876.

Augustus Phillimore, R.-Adm. (V.-Adm. 1879).

Nov. 21, 1879.

H.R.H. Alfred Ernest Albert, Duke of Edinburgh, K.G., etc.,

R.-Adm.

Nov. 23, 1882. Sir

Anthony Hiley Hoskins, K.C.B., R.-Adm. (V.-Adm. 1885).

Sept. 6, 1885.

John Kennedy Erskine Baird, R.-Adm. (V.-Adm. 1886).

Apr. 17, 1888. Sir

George Tryon, K.C.B., R.-Adm. (V.-Adm. 1889).

Apr. 21, 1891.

Robert O'Brien FitzRoy, C.B., R.-Adm.

Apr. 25, 1894.

Edward Hobart Seymour, C.B., R.-Adm. (V.-Adm. 1895).

May 10, 1897. Compton Edward Domvile, V.-Adm. (K.C.B. 1898).

May 21, 1900. Sir

Gerard Henry Uctred Noel, K.C.M.G., R.- Adm.

DIRECTOR OF NAVAL

INTELLIGENCE.

Feb. 1, 1887.

William Henry Hall, Capt., R.N.

Jan. 1, 1889.

Cyprian Arthur George Bridge, Capt., R.N. (R.-Adm. 1892).

Sept. 1, 1894.

Lewis Anthony Beaumont, Capt., R.N. (R.-Adm. 1897).

Mar. 20, 1899.

Reginald Neville Custance, C.M.G., Capt., R.N. (R.-Adm. 1899).

SUPERINTENDENTS OF H.M. DOCKYARDS.

Chatham.

George Goldsmith,

C.B., Capt., R.N.

Apr. 1, 1861.

Edward Gennys Fanshawe, Capt., R.N.

Nov. 19, 1863.

William Houston Stewart, C.B., Capt, R.N.

Dec. 1,1868.

William Charles Chamberlain, Capt., R.N.

Jan. 19, 1874.

Charles Fellowes, C.B., Capt., R.N. (R.-Adm. 1876).

Feb. 3, 1879.

Thomas Brandreth, R.-Adm.

Dec. 1, 1881.

Georges Willes Watson, R.-Adm. (V.-Adm. 1886).

May 1,1886.

William Codrington, C.B., R.-Adm.

Nov. 1, 1887.

Edward Kelly, R.-Adm.

Jan. 25, 1892.

George Digby Morant, R.-Adm. (V.-Adm. 1895).

Sept. 2, 1895.

Hilary Gustavus Andoe, C.B., R.-Adm.

Sept. 2, 1899.

Swinton Colthurst Holland, R.-Adm.

Portsmouth.

William Fanshawe

Martin, R.-Adm.

Feb. 25, 1858.

Hon. George Grey (2) R.-Adm.

Feb. 19, 1863.

George Elliot (4), R.-Adm.

July 1, 1865.

George Greville Wellesley, C.B., R.-Adm.

July 1, 1869.

Astley Cooper Key, C.B., R.-Adm.

Nov. 20, 1871.

William Houston Stewart, C.B., R.-Adm.

Apr. 29, 1872. Sir

Francis Leopold M'Clintock, R.-Adm.

Apr. 30, 1877.

Hon. Fitzgerald Algernon Charles Foley, R-.Adm. (V.-Adm. 1881).

May 1, 1882. John

Dobree M'Crea, R.-Adm.

Apr. 6, 1883.

Frederick Anstruther Herbert, R.-Adm.

Nov. 1, 1886. John

Ommanney Hopkins, R.-Adm.

Aug. 6, 1888.

William Elrington Gordon, R.-Adm.

May 21, 1891. John

Arbuthnot Fisher, C.B., R.-Adm.

Feb. 1, 1892.

Charles George Fane, R.- Adm.

Feb. 1, 1896.

Ernest Rice, R.-Adm. (V.- Adm. 1899).

Sept. 1, 1899. Pelham Aldrich, R.-Adm.

Devonport.

Feb. 19,1855. Sir James Hanway Plumridge, K.C.B., R.-Adm.

Dec. 9, 1857. Sir Thomas Sabine Pasley, Bart., R.-Adm.

Nov. 28, 1862. Thomas Matthew Charles Symonds, C.B., R.-Adm.

May 9, 1866. Hon. James Robert Drummond, C.B., R.-Adm.

July 13, 1870. William Houston Stewart, C.B., R.-Adm.

Nov. 22, 1871. Sir William King Hall, K.C.B., R.-Adm.

Aug. 12, 1875. William Charles Chamberlain, R.-Adm.

May 1, 1876. George Ommanney Willes, C.B., R.-Adm.

Feb. 1, 1879. Charles Webley Hope, R.-Adm.

Feb. 23, 1880. Charles Thomas Curme, R.-Adm.

Feb. 23,1885. John Crawford Wilson, R.-Adm. (died).

July 10, 1885.

Henry Duncan Grant, C.B., R.-Adm. (V.-Adm. 1888).

Aug. 4, 1891. Sir

Robert Henry More-Molyneux, K.C.B., R.-Adm. (V.-Adm. 1894).

Aug. 7, 1894.

Edmund John Church, R.-Adm.

Nov. 3, 1896.

Henry John Carr, R.-Adm.

July 7, 1899.

Thomas Sturges Jackson, R.-Adm.

Woolwich

("Commod. in Charge").

(Dec. 31, 1853.)

John Shepherd (2), Commod. 2nd Cl.

Dec. 20, 1858.

Hon. James Robert Drummond, Commod., 2nd Cl.

June 29, 1861. Sir

Frederick William Erskine Nicholson, Bart., Commod., 2nd Cl.

Jan. 1, 1864. Hugh

Dunlop, C.B., Commod., 2nd Cl.

Apr. 9, 1866.

William Edmonstone.C.B., Commod., 2nd Cl.

(Dockyard

closed 1869.)

Deptford.

Horatio Thomas

Austin, C.B., Capt., R.N.

Dec. 12, 1857.

Claude Henry Mason Buckle, C.B., Capt., R.N.

Feb. 9, 1863.

Henry Chads, Capt., R.N.

Apr. 10, 1866. Arthur Parry Eardley Wilmot, C.B., Capt., R.N.

(Dockyard

closed, 1869.)

Sheerness.

John Jervis

Tucker, Capt., R.N.

Sept. 23, 1857.

John Coghlan Fitzgerald, Capt., R.N.

June 9, 1859.

Rundle Surges Watson, C.B., Capt., R.N.

July 3, 1860.

Charles Wise, Capt., R.N.

Apr. 27, 1865.

William King Hall, C.B., Capt., R.N.

Apr. 1, 1869. Hon.

Arthur Auckland Leopold Pedro Cochrane, C.B., Capt., R.N.

May 25, 1870.

William Garnham Luard, C.B., Capt., R.N.

Jan. 9, 1875. Hon.

Fitzgerald Algernon Charles Foley, Capt., R.N.

Jan. 9, 1877.

Thomas Brandreth, Capt., R.N.

Jan. 4, 1879.

Theodore Morton Jones, Capt. R.N.

Jan. 1, 1883.

John Ommanney Hopkins, Capt., R.N.

Apr. 6,1883.

William Codrington, C.B.. Capt., R.N.

July 17, 1885.

Henry Frederick Nicholson, C.B., Capt.. R.N.

July 1, 1886. Sir

Robert Henry More-Molyneux, K.C.B., Capt., R.N.

June 1,1888.

Charles George Fane, Capt., R.N.

Aug. 6, 1890.

Richard Duckworth King, Capt., R.N.

Jan. 25, 1892.

Armand Temple Powlett, Capt. R.N.

Jan. 1, 1894. John

Fellowes, C.B., Capt., R.N.

Jan. 15, 1895.

John Coke Burnell, Capt., R.N.

Jan. 11, 1898.

Andrew Kennedy Bickford, C.M.G., Capt., R.N.

June 28, 1899.

Reginald Friend Hannam Henderson, C.B., Capt., R.N.

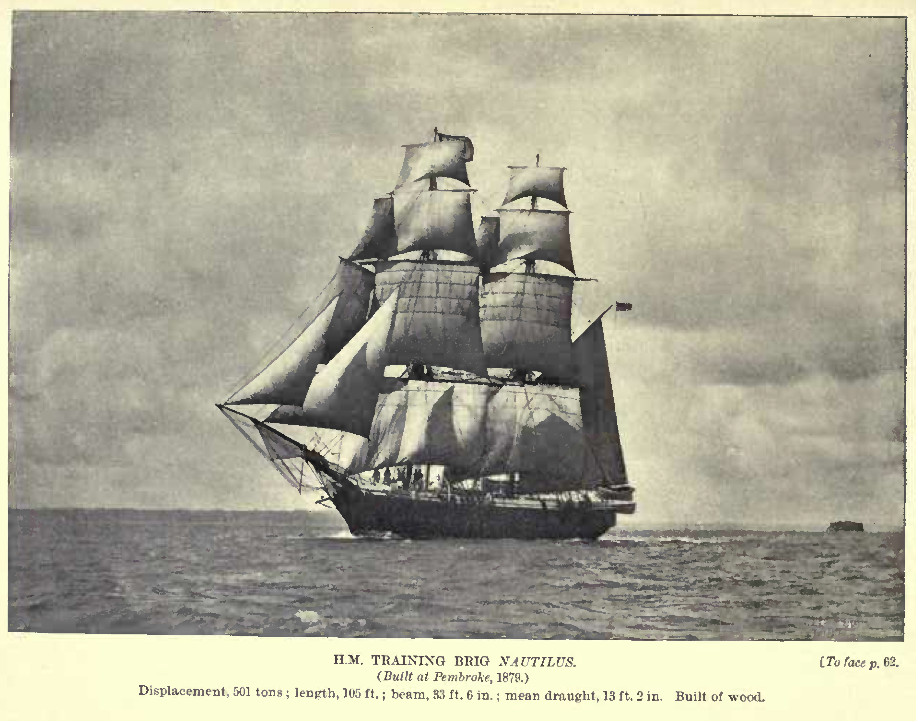

Pembroke.

(May 22, 1854.)

Robert Smart, K.H., Capt., R.N.

July 27, 1857.

George Ramsay, C.B., Capt., R.N.

Sept. 1, 1862.

William Loring, C.B., Capt., R.N.

Mar. 21, 1866.

Robert Hall (3), C.B., Capt., R.N.

Mar. 22,1871.

William Armytage, Capt. , R.N.

Mar. 15, 1875.

Richard Vesey Hamilton, Capt., R.N.

Oct. 16, 1877.

George Henry Parkin, Capt., R.N.

Oct. 15, 1882.

Alfred John Chatfield, Capt., R.N.

Jan. 1, 1886.

Edward Kelly, Capt., R.N.

June 22, 1887.

George Digby Morant, Capt., R.N.

Jan. 7, 1889.

Samuel Long, Capt., R.N.

Aug. 28, 1891.

Walter Stewart, Capt., R.N.

Jan. 1, 1893.

Charles Cooper Penrose FitzGerald, Capt., R.N.

Mar. 21, 1895. Charles John Balfour, Capt., R.N.

(In 1895 Capt. William Henry Hall, appointed to succeed Capt. FitzGerald,, died before he assumed office.).

Oct. 4, 1896.

Burges Watson, Capt., R.N.

Oct. 2, 1899.

Charles James Barlow, D.S.O., Capt., R.N.

Gibraltar ("N.O.

in Charge ").

Apr. 14, 1862.

Erasmus Ommanney, Capt., R.N.

Jan. 1, 1865.

James Charles Prevost, Capt., R.N.

Feb. 1, 1870.

Augustus Phillimore, Capt., R.N.

Jan. 1, 1874. John

Dobree M'Crea, Capt., R.N.

Jan. 16, 1878.

William Henry Edye, Capt, R.N.

Jan. 10, 1881.

Hon. Edmund Robert Fremantle, Capt., R.N.

Dec. 27, 1883.

John Child Purvis (2), Capt., R.N.

Dec. 15, 1886. Henry Craven St. John, Capt., R.N.

Sept. 3, 1889.

Claude Edward Buckle, Capt., R.N.

Jan. 7, 1892.

Atwell Peregrine Macleod Lake, Capt., R.N.

Jan. 20, 1895.

John Andrew Thomas Bruce, Capt., R.N.

Jan. 20, 1898.

Charles Carter Drury, Capt., R.N.

Sept. 1, 1899.

William Harvey Pigott, Capt., R.N.

Malta.

Hon. Sir Montagu

Stopford, K.C.B., R.-Adm.

July 27, 1858.

Henry John Codrington, C.B., R.-Adm.

Apr. 6, 1863.

Horatio Thomas Austin, C.B., R.-Adm.

Nov. 26, 1864.

Henry Kellett, C.B., R.-Adm.

May 25, 1868.

Edward Gennys Fanshawe, R.-Adm.

June 6, 1870.

Astley Cooper Key, C.B., R.-Adm.

Aug. 8, 1872. Sir

Edward Augustus Inglefield, Kt., C.B., R.-Adm.

Dec. 22, 1875.

Edward Bridges Rice, R.-Adm.

May 30, 1876.

William Garnham Luard, C.B., R.-Adm (temp.).

Apr. 13, 1878.

William Garnham Luard, C.B., R.-Adm.

July 18, 1879.

John Dobree M'Crea, R.-Adm.

Mar. 24, 1882.

William Graham, C.B., R,-Adm.

Mar. 25,1885. Hon.

William John Ward, R.-Adm.

May 4, 1887.

Robert Gordon Douglas, R.-Adm.

Jan. 10, 1889.

Alexander Buller, R.-Adm.

Jan. 12, 1892.

Richard Edward Tracey, R.-Adm.

Jan. 20, 1894.

Richard Duckworth King, R.-Adm.

Feb. 1, 1897.

Rodney Maclaine Lloyd, C.B., R.-Adm.

Feb. 1, 1900. Burges Watson, R.-Adm.

REORGANISATION OF THE ADMIRALTY. 9

Some of the changes in the administrative methods of the Admiralty may be traced in the foregoing. Under the rule of Mr. Childers it was felt that the position of the Controller, who had not then a seat at the Board, was anomalous and unsatisfactory; and, by an Order in Council of January 14th, 1869, the Board was accordingly reconstructed, as follows:

|

THE OLD BOARD. The First Lord. Four Naval Lords. The Civil Lord. The First, or Parliamentary

Secretary. The Second, or Permanent Secretary. |

THE NEW BOARD. The First Lord. The First Naval Lord. The Third Lord and Controller. The Junior Naval Lord. The Civil Lord. The Parliamentary Secretary. The Permanent Secretary. |

10 CIVIL HISTORY

OF THE ROYAL NAVY, 1857-1900.

The Order, however, besides effecting this reconstruction, restricted each Lord to the peculiar business assigned to him, and so rendered meetings of the Board almost unnecessary. An embarrassment of affairs resulted. It was sought to reduce this by creating temporarily a "Chief of the Staff," by establishing the Contract and Purchase Department, and by transferring the offices of the Civil Departments from Somerset House to Whitehall and Spring Gardens.

Under Mr. Goschen, a new Order in Council, of March 19th, 1872, made all the Lords directly responsible to the First Lord, appointed a Second Naval Lord, deprived the Controller of his seat, and added to the Board a Third, or Naval Secretary. But under Lord Northbrook, by Order in Council of March 10th, 1882, the Naval Secretary disappeared, the Permanent Secretary was revived, the Controller resumed his seat at the Board, and a non-parliamentary Civil Lord was given him as his assistant. This non-parliamentary Civil Lord (Mr. George Wightwick Rendel) disappeared in 1885; and, at about the same time, the Accountant-General of the Navy was ordered to act as deputy and assistant to the Parliamentary and Financial Secretary (O. in C. of Nov. 18, 1885).

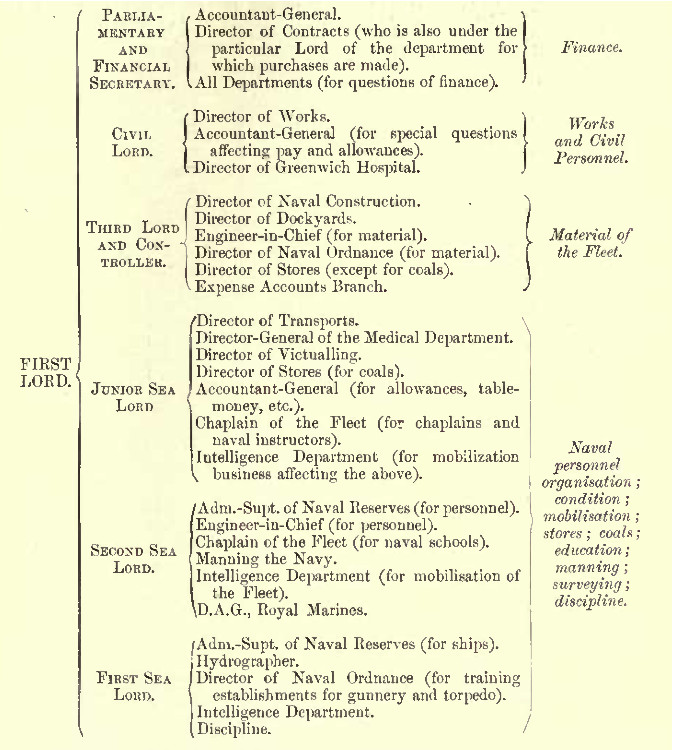

The Board as thereafter constituted consisted of:

The First Lord

(salary £4500, with house).

The First Sea Lord

(salary £1500, with house, and naval pay).

The Second Sea

Lord (salary £1200, with naval pay).

The Third Lord and

Controller (salary £1700, with naval pay).

The Junior Sea

Lord (salary £1200).

The Civil Lord

(salary £1000).

The Parliamentary

and Financial Secretary (salary £2000).

The Permanent Secretary (salary £2000).

CONSTITUTION OF

THE ADMIRALTY. 11

The manner in which the business of the Board

is divided, and the relationship of the various Lords and the

Parliamentary Secretary to the subsidiary departments, is shown

in the following table, which is adapted from Admiral Sir E.

Vesey Hamilton's useful volume on 'Naval Administration' (1896):

The business of the Permanent Secretary is to

superintend all correspondence in the name of the Board; to

prevent independent action by any department; to provide for the

transmission and execution of orders; and to keep unbroken the

administrative machinery of the Admiralty.

12

CIVIL HISTORY OF THE ROYAL NAVY, 1857-1900.

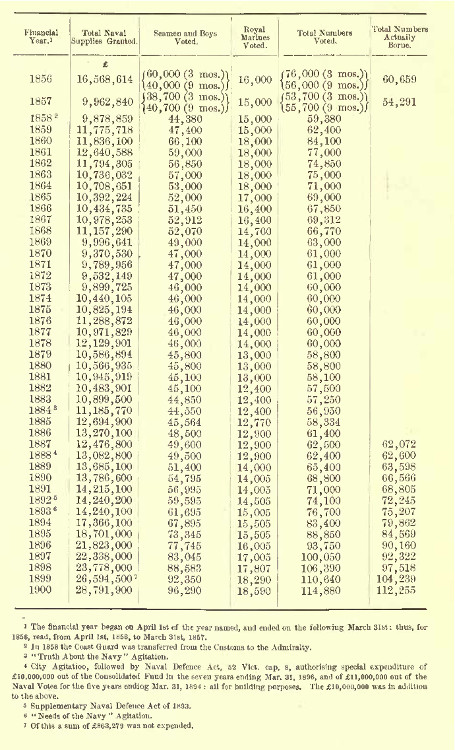

The sums voted for the service of the Navy, and the numbers of seamen and Royal Marines authorised to be borne each from 1856-57 to 1900-01 inclusive were:

STRENGTH OF THE

OFFICERS' LIST. 13

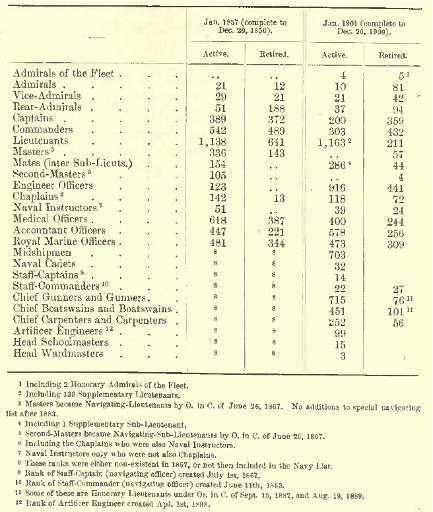

During the changeful and progressive period

under review, immense alterations, as might be expected, were

made in the constitution of the active list of officers. For

convenience of reference, the numbers of officers of the various

ranks, both active and retired, included in the official lists

for January, 1857, and January, 1901, respectively, are here

given side by side:

Although there was no Admiral of the Fleet at the beginning of 1857, the rank was in temporary abeyance only. Admiral of the Fleet Sir Thomas Byam Martin had died in October, 1854, leaving Admiral Thomas Le Marchant Gosselin at the head of the active list. Gosselin, though in the early part of his career he had been on full pay for twenty-nine years, had subsequently been on half-pay for no fewer than forty-five years in succession, and had never hoisted his flag. Moreover, he was eighty-nine years of age. He lived, nevertheless,

14 CIVIL

HISTORY OF THE ROYAL NAVY, 1857-1900.

until nearly the last days of 1857. Not until

then was the officer next on the list, Admiral Sir Charles Ogle,

Bart., promoted. Ogle had hoisted his flag more than once; and

his claim to promotion, when his turn came, could hardly have

been resisted. Nevertheless, be it noted, although Gosselin had

not been promoted, he had not been passed over. While he lived

he simply, as it were, blocked the way.

For many years after 1857 the flag-officer at

the top of the list of Admirals always received promotion as a

vacancy occurred; and in 1862 a second Admiral of the Fleet was

appointed, a third being added in 1863. Three remained the

extreme number until nearly the close of the century. In making

the appointments, provided that the officer next on the list had

served as a Commander-in-Chief, or had commanded at sea as a

flag-officer for two years, seniority was never ignored until,

in 1892, came the turn of Admiral Algernon Frederick Rous de

Horsey, who had been Commander-in-Chief in the Pacific for

nearly three years, and, in addition, had been senior officer in

the Channel for about five months.

On that occasion, her Majesty the Queen,

exercising her right of selection, saw fit to pass over de

Horsey, and to promote Sir John Edmund Commerell, whose name

stood next on the active list. Thenceforward seniority, subject

to the provisions above indicated, was not interfered with,

except in the case of H.R.H. the Duke of Edinburgh, 1

until 1898, when Sir Frederick William Richards 2

was promoted as a fourth Admiral of the Fleet, although, at the

time, he was not next on the list, but third on it. This

promotion, however, differed from that of Commerell in that it

was an extra one, and was not made to the permanent prejudice of

any other officers; for when, in 1899, the turn came of the

officer, Sir Nowell Salmon, who had all along stood first for

promotion (assuming an establishment of only three Admirals of

the Fleet), he was promoted.

It may be noted here that the rank of

Honorary Admiral of the Fleet was first created in 1887 in

favour of his present Majesty, then Prince of Wales, on the

occasion of Queen Victoria's Jubilee, and that his Majesty,

William II., German Emperor, was honoured with the like dignity

in 1889.

1

O. in C. of Nov. 23, 1893.

2 O. in C. of Nov. 29, 1898.

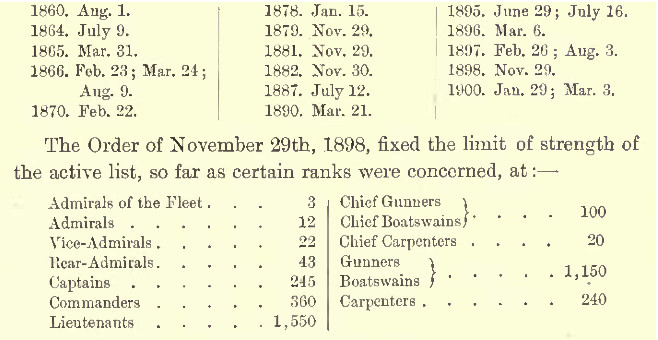

CHANGES IN

OFFICERS' RANK. 15

On July 9th, 1864, an Order in Council

discontinued the time-honoured classification which had

previously subdivided the various ranks of flag-officers into

those of the Red, the White, and the Blue Squadrons

respectively; and by an Admiralty circular of August 5th

following it was directed that, for the future, all

flag-officers should wear a white flag with a red Cross of St.

George therein, with, in the case of Vice-Admirals, one red

ball, and, in the case of Rear-Admirals, two red balls, in the

upper part, near the staff.

At the same time it was ordered that all

Commodores should wear a white broad-pennant, with a red St.

George's Cross therein; that all her Majesty's ships in

commission should fly the White Ensign; that the Blue Ensign

should be borne by vessels " n the service of any public

office," and by ships commanded by officers of the Royal Naval

Keserve, 1 and having

a fourth part of the crew composed of reserve men; and that the

Red Ensign should continue to be flown by all other British

vessels, with the exception of certain yachts, and craft

authorised to bear distinguishing flags.

An Order in Council of June 26, 1867,

transformed the then existing

Masters into

Navigating-Lieutenants;

the Second Masters

into Navigating-Sub-Lieutenants;

the Masters'

Assistants into Navigating-Midshipmen; and

the Naval Cadets,

2nd Class, into Navigating-Cadets.

The title of

Sub-Lieutenant was substituted for that of Mate in 1861.

The commissioned

ranks of Chief Gunner, Chief Boatswain, and Chief Carpenter were

created by an Admiralty Circular of July 25th, 1864.

It is impossible to say much here on the

large subject of naval retirement. The chief Orders in Council

which affected it during the period under review are those of:

1

See also Circ. of Aug. 3, 1864.

16 CIVIL HISTORY

OF THE ROYAL NAVY, 1857-1900.

and made provision for the rate at which the

flag-officers', Captains', and Commanders' lists were to be

increased annually. In several of the ranks at the end of the

century (see Table on p. 13) the numbers fell far short of what

they then should have been.

Under the regulations which remained in force

at the end of 1900:

Admirals of the

Fleet were compulsorily retired at seventy;

Admirals,

at sixty-five (or seven years after last active service);

Vice-Admirals at

sixty-five (or seven years after last active service);

Rear-Admirals at

sixty (or seven years after last active service);

Captains at

fifty-five (or six years after last active service);

Commanders at

fifty (or five years after last active service);

Lieutenants at

forty-five (or four years after last active service);

Chief Inspectors

and Inspectors of Machinery at sixty (or seven years after last

active service);

Fleet Engineers,

Staff Engineers, and Chief Engineers at fifty-five (or five

years after last active service);

Engineers at

forty-five (or five years after last active service);

Assistant

Engineers at forty (or five years after last active service);

Chaplains and

Naval Instructors at sixty;

Inspectors-General,

and Deputy Inspectors-General of Hospitals at sixty;

Fleet Surgeons,

Staff Surgeons, and Surgeons at fifty-five; and

Fleet Paymasters,

Staff Paymasters and Paymasters at sixty.

All things considered, the pay of naval

officers underwent singularly little alteration during the

period. The good executive officer of 1857 was, relatively

speaking, little more scientific than his predecessor of 1805.

It was not necessary that he should know much about steam; the

gunnery requirements of the day were simple; and hydraulics,

electricity, Morse signalling, and torpedoes were unknown in the

service. On the other hand, it was required of the good

executive officer of 1900 that he should be not only a seaman

and a gunner, but also something of an engineer, something of a

physicist, something of a chemist, and much more.

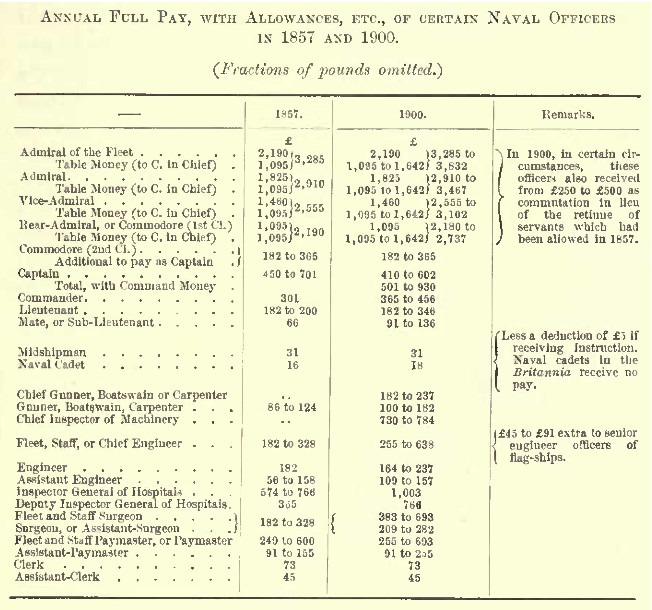

Yet his emoluments were hardly increased in proportion. Still more modestly were the emoluments of the Accountant branch added to. The most notable advances were in the pay of officers of the purely and avowedly scientific branches, the engineering and the medical. It is impracticable to give here a full statement of all such changes as were made; but the full pay received by officers of a few typical ranks and standings in 1857 and 1900 respectively is shown in the appended table:

PAY AND WAGES. 17

The continuous service

(annual) wages of Able Seamen (£28 17s. 11d.),

Ordinary Seamen (£22 16s. 3d.), and First Class Boys (£10 12s.

11d.), fixed in 1853, were not altered ere the end of the

century; but the introduction of extra pay for good conduct

badges, for re-engagement, etc., and the creation of numerous

new and specially paid ratings, gave the ambitious and capable

seaman many opportunities of increasing his wages from time to

time, and vastly ameliorated his financial prospects.

Up to 1859 the naval reserves of the country consisted of:

(a) Royal Marines

quartered ashore;

(b) the Coast

Guard, which in the previous year had been transferred from the

control of the Customs to that of the Admiralty;

(c) the Royal

Naval Coast Volunteers l;

and

(d) short service

pensioners.

In spite of the introduction of the

Continuous Service System, 2

in 1853, and of the entry of seamen for ten years,

considerable difficulty was still

experienced in manning the fleet. For example, the Diadem,

commissioned in August, 1857, could not complete her crew until

January, 1858; the Renown, commissioned in November 1 detained

by lack of men for 172 days, and then sailed 62 short of her

complement; and the Marlborough, commissioned in February 1858,

was similarly delayed for 129 days.

1

Raised 1853. They died out in 1873.

2

See Vol. VI. p. 207.

18 CIVIL HISTORY

OF THE ROYAL NAVY, 1857-1900.

To consider this unsatisfactory condition of

affairs, and to make recommendations for its amelioration, a

Royal Commission was appointed. It reported on February 19th,

1859, advocating among other things, the maintenance of at least

five large training-ships for the preparation of boys for the

Navy; the creation of larger reserves; the better training of

the reserves in gunnery; improvements in the comforts and

dietary of seamen; modifications in the system of the payment of

wages, and of allotments, etc., etc.

The first effect of the report was the issue,

on April 27th, 1859, of an Admiralty Order, which slightly

altered the scale of victualling 1;

authorised the supply to all boys and men on joining of bed,

blanket, and bedcover, free of charge; gave continuous service

men, on entering, and boys, on being rated as men a free part

kit, or money in lieu of it 2;

and promised the gratuitous supply to ships commissioning of

mess utensils, so soon as suitable ones be found.

Other results which followed were the increase of the Marines, and of the Coast Guard, the introduction of training-ships for boys, and the establishment of a corps of Royal Naval Volunteers, a force which ultimately developed into the Royal Naval Reserve, the earliest commissions to which, as such, were dated in February, 1862. Various regulations for the officers this corps were subsequently embodied in Orders in Council dated respectively March 1st, 1864, October 15th, 1872, June 28th, 1 and May 3rd, 1882. These were consolidated and revised by an Order of June 26th, 1886, which was further modified by Orders of February 7th, 1888, July 23rd, 1889, February 23rd, 1891, March 20th 1891, May 9th, 1892, and May 16th, 1893. The whole regulations were again consolidated and revised in 1896; when the number of officers was fixed at 1800.

1.

Allowance of biscuit per man per diem increased from 1 lb to 1

1/4 ib, but savings' price per pound reduced from 2d to 1 1/2

d. Allowance of sugar per man per diem increased from 1 3/4

ozs. to 2 ozs. Extra allowance in middle or morning watch at

Captain's discretion, of 1/2 oz. of sugar and 1/2 oz of

chocolate to men sick or specially exposed.

NAVAL RESERVES.

19

A new force, the Royal Fleet Reserve, designed to consist of seamen and Royal Marines who have been discharged with or without pensions, and eventually to supersede the old seamen pensioner reserve, was planned and decided upon in 1900 but no men were entered until later. In the same year also two important steps were taken towards the creation of additional and more efficient naval reserve forces in her Majesty's dominions beyond the seas. New Zealand initiated the discussion among the Australasian colonies of a project for the establishment of reserves both military and naval; and fifty Newfoundland fishermen belonging to the naval reserve of the island were embarked in H.M.S. Charybdis, Captain George Augustus Giffard, for a six months' training cruise in the West Indies. Concerning the ordinary naval resources of the colonies a few words will be said later. 1

For nearly twenty years, towards the end of

the century, yet another naval reserve existed in the shape of

the Royal Naval Artillery Volunteers, which were raised under an

Act of August 5th, 1873. 2

This body was intended to provide trained gunners for service

within the home seas, and consisted for the most part of

yacht-owners and professional men of good social standing. Its

headquarters and drill-ship (first the Rainbow, and later the

Frolic) was moored in the Thames, off Somerset House. Owing to

regrettable misunderstandings, frictions and jealousies, the

corps was disbanded on April 1st, 1892. A few months before that

date it had included 66 officers and 1849 men. 3

1

See p. 77 and note.

2

Modified in 1882 by the National Defence Act.

3

Report of Sir G. Tryon's Committee, Apr. 7, 1891.

20 CIVIL HISTORY

OF THE ROYAL NAVY, 1857-1900.

THE FIRST

IRONCLADS

For several years after 1856 the construction of wooden men-of-war, 1 of all classes, continued. The lessons of Kinburn, indeed, seemed to produce in England no tangible results whatsoever until the spring of 1859, when the first British sea-going armoured iron ship, the Warrior, was laid down at Blackwall. The armoured wooden floating batteries of the Trusty class, and the armoured iron floating batteries of the Erebus class, 2 built in 1854-56, remained, up to the Warrior's launch in December, 1860, the only ironclads belonging to her Majesty's fleet. Progress was at length forced upon the country by the action of France, which, suspending the completion of the original designs of four large and fast wooden screw ships which she had upon the stocks at Brest and Toulon, had begun to armour them, and to convert them from 90-gun vessels of the line to 36-gun frigates. One of these, the Gloire, was actually launched in November, 1859.

FS Gloire |

HMS Warrior (Cyber-Heritage) |

Great Britain also adapted as ironclads a certain number of fine wooden ships which were available for the purpose at the time when it became evident that the armoured vessel must be the battleship of the future. These adapted ships were the following:

HMS Ocean (Wikipedia) |

HMS Royal Alfred |

Royal

Oak, Caledonia, Prince Consort, and

Ocean, originally designed and begun as wooden

line-of-battleships of 91 guns, 3716 tons (old measurement), and

800 H.P. nom., but converted, in accordance with an Admiralty

Order of May 14, 1861, to armour-plated ships of about 6400 tons

displacement, and from 3700 to 4240 H.P.I. As adapted, they were

full-rigged broadside ships, with iron armour of a maximum

thickness of 4.5 inches, carrying 24 6.5-ton 7-in.

muzzle-loaders. They had single screws, and an extreme speed of

from 12 to 13 knots. All were launched in 1862 and 1863.

Royal Alfred, originally designed and begun as a wooden line-of-battle ship of 91 guns, 3716 tons (old measurement), and 800 H.P. nom., but converted, in accordance with an Admiralty Order of June 5, 1861, to an armour-plated ship of 6720 tons' displacement, and 3434 H.P.I. As adapted, she was a full-rigged broadside ship, with iron armour of a maximum thickness of 6 inches, carrying 18 6.5-ton 7-in. muzzle-loaders. She had a single screw, and a speed of 12.3 knots, and was launched in 1864.

1

This sketch of the progress of Naval Architecture during the

years 1857-1900 is mainly based upon the following

authorities: King, 'The Warships of Europe' (1878); Very,

'Navies of the World' (1880); Heed, 'Our Ironclad Ships'

(1869); Brassey, 'The British Navy' (1882-83); White, 'A

Manual of Naval Architecture' (1882); The Catalogue of the

Museum at Greenwich, and the Collection of Ship Models

there; Brassey, 'The Naval Annual' (1886-1901); Clowes, 'The

Naval Pocket Book' (1896, etc.); Lloyd's 'Warships of the

World' (annually); Busk, 'The Navies of the World ' (1859);

Armstrong, 'Torpedoes and Torpedo Vessels' (1896); Williams,

'The Steam Navy of England' (1893); and numerous articles

and papers, especially in the Transactions of the

Institution of Naval Architects; The Year's Naval Progress

(Washington); the Journal of the Royal United Service

Institution; the Proceedings of the United States' Naval

Institute (Annapolis); the Engineer; and Engineering.

2 See Vol. vi., p. 198.

THE FIRST

IRONCLADS. 21

HMS Repulse |

HMS Favorite

|

HMS Research |

Repulse,

originally designed and begun as a wooden line-of-battle ship of

90 guns, 3074 tons (old measurement), and 800 H.P. nom., but

converted, in accordance with an Admiralty Order of October 9,

1866, to an armour-plated ship of 6190 tons' displacement, and

3350 H.P.I. As adapted, she was a full-rigged broadside ship,

with iron armour of a maximum thickness of 6 inches, carrying 12

8-in. 9-ton (but later 10 9-in. 12-ton) muzzle-loaders. She had

a single screw, and a speed of about 12 knots, and was launched

in 1868.

Favorite,

originally designed and begun as a wooden corvette of 22 guns,

but converted, according to designs by Mr. E. J. Reed and the

Controller's Department, in 1862, to a rigged, armour-plated

corvette of 3169 tons' displacement, and 1773 H.P.I., with iron

armour of a maximum thickness of 4.5 inches, carrying 10 8-in.

9-ton muzzle-loaders. She had a single screw, and a speed of

11.8 knots, and was launched in 1864.

Research,

designed and begun as a wooden 17-gun sloop in 1861, but

converted in 1862 to an armoured, rigged vessel, and launched in

1863. Displacement, 1680 tons; speed 10.3 knots; thickest armour

4.5 inches; 4 7-in. 6.5-ton muzzle-loaders.

The above, as converted, differed outwardly

in no essential respects from their immediate predecessors, the

wooden screw battleships and frigates. They were still fine

specimens of the old picturesque style of naval architecture,

and were fairly good craft under sail.

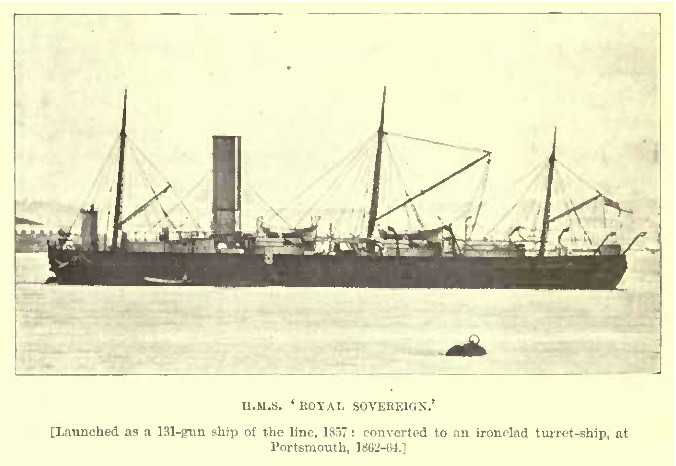

The only other wooden ship, the Royal Sovereign, which was converted to an ironclad for the British Navy received very different treatment. She was cut down, armoured all over, supplied merely with three light pole masts, and furnished with four armoured revolving turrets, which were placed on the upper deck in the middle line of the ship. Although herself of little practical use, she was a most important and significant craft, in that she embodied the first British admission of two novel principles which, many years afterwards, obtained universal acceptance; viz., that sail-power had ceased to be useful in vessels intended for heavy fighting; and that the main armament of every ship intended for heavy fighting should be protected as completely as possible, and should moreover be so mounted as to have as near an approach as might be to all-round fire. In addition, possessing a relatively low freeboard, the converted Royal Sovereign had the advantage. of offering but a proportionately small target to an enemy. These features were all due to the advocacy of Captain Cowper Phipps Coles, R.N., C.B.

Royal Sovereign, originally launched in 1857 as a wooden line-of-battle ship of 131 guns, 3765 tons (old measurement), and 800 H.P. nom., was converted, in accordance with an Admiralty Order of April 3rd, 1862, to an armoured turret-ship of 4965 tons' displacement, and 800 H.P. nom. As adapted, she had iron armour of a maximum thickness of 5.5 inches, and carried 5 9-in. 12-ton muzzle-loaders, one in each of her three aftermost turrets, and two in the foremost one. She had a single screw, and a speed of 11 knots, and was undocked in 1864.

22 CIVIL HISTORY OF THE ROYAL NAVY, 1857-1900.

It has been said that the iron-hulled armoured ship Warrior was laid down in the spring of 1859; yet it should be added here that, for several years later, the Admiralty seemed unable to make up its mind whether, after all, iron was or was not to be the building material of future heavy fighting ships. In that period of apparent doubt and hesitation it caused both iron-hulled and wooden-hulled armoured ships to be constructed. The wooden-hulled ones are briefly noted below:

HMS Lord Clyde |

HMS Zealous |

HMS Pallas |

Lord

Clyde and Lord

Warden, laid down in 1863, after designs by Mr. E. J.

Reed, and the Controller's Department, as single-screw,

wooden-hulled, armoured broadside ships of 7602 and 7839 tons'

displacement, and 6034 and 6706 H.P.I, respectively; each fully

rigged, and ultimately carrying 18 6-ton 7-in. muzzle-loaders.

Speed, about 13.5 knots. Launched respectively in 1864 and 1865.

Maximum thickness of iron armour 5 inches.

Zealous, laid down in October, 1859, after designs by the same, as a single-screw, wooden-hulled, armoured, broadside ship of 6102 tons' displacement, and 3623 H.P.I.; rigged; and ultimately carrying 20 6.5-ton 7-in. muzzle-loaders. Speed, 11.7 knots. Launched in 1864. Maximum thickness of iron armour, 4.5 inches.

IRON AS A

BU1LDING MATERIAL. 23

Pallas

(laid down 1863, launched 1865), a single-screw, wooden-hulled,

rigged, armoured, broadside corvette, designed by Mr. E. J.

Reed, and the Controller's Department. Displacement, 3661 tons;

H.P.I., 3581; speed 13 knots; maximum thickness of armour 4.5

inches; ultimate armament, 8 8-in. 9-ton muzzle-loaders.

Enterprise,

laid down in 1862, after designs by the same, as a single-screw,

wooden-hulled, rigged, armoured sloop of 993 tons' displacement,

and 9.9 knots' speed, carrying 4 7-in. 6.5 ton guns. Launched in

1864. Maximum thickness of iron armour, 4.5 inches. In this

case, although the hull was of wood the upper works were of iron

(composite construction).

HMS Black Prince, sister-ship to HMS Warrior

Thus, from 1859 until 1866, the Admiralty still thought it worth while either to build wooden ironclads or to armour existing wooden hulls. From 1866, however, that idea was definitely abandoned, the Order for the conversion of the Repulse being the final symptom of official hesitation.

The rise of

the iron-built, sea-going ironclad, and its development may

now be studied without further interruption.

At first the traditions of the old wooden

navy greatly influenced the designs of all new fighting-ships,

and vessels continued to be built not only with heavy rigging

and large sail-power, but also with their guns disposed, as

previously, in broadside along the major parts of their length.

The armoured ships, arranged in order of their launch, which

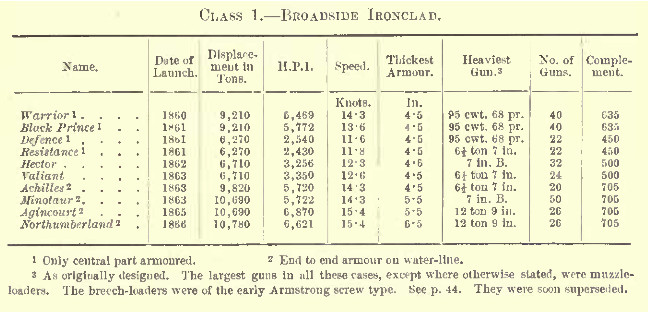

were constructed on this principle were:

24 CIVIL HISTORY

OF THE ROYAL NAVY, 1857-1900.

The next

developments which were generally adopted were

the confinement of the heavy armament of the ironclad vessel

to a central battery, where it was mounted behind

comparatively thick iron armour, and shut off fore and aft by

armoured bulkheads; and the restriction of armour elsewhere to

the neighbourhood of the water-line. The ships of this class, as

successively launched, are catalogued below. All were, as

before, heavily rigged; and, as regards general appearance, the

old lines were preserved, except that the ram bow, 1

which was not introduced in some of the earliest ironclads, and

which was adopted largely in consequence of the advocacy of

Admiral Sir George Kose Sartorius, had become a regular feature.

Each of the above had a complete water-line belt, with good protection over the central battery. The Alexandra was the earliest of the above to be provided with a substantial deck of steel in the neighbourhood of the water-line; but it was not curved below the water-line at its edges, and was not so arranged as to deflect upwards any projectiles that might enter the vessel near the line of flotation, and thus to protect the machinery. In her case this deck was two inches thick. It was mainly designed as a protection against plunging fire. Save for this belt, the entire hull of the Alexandra, as of the other craft in the list, was of iron, neither compound armour nor steel as a building material having yet come into use.

1 The popular and exaggerated estimate of the value of this (the ram) was greatly increased in 1875, when, on Sept. 2, the Iron Duke, in a fog off Wicklow, accidentally rammed her sister ship, the Vanguard, which sank within an hour. As a matter of fact, the ram has proved to be more dangerous in accident than formidable in action. See Author's Lecture at R.U.S.I., Jan. 19, 1894.

EXPERIMENTAL

TYPES OF FIGHTING SHIPS. 25

Although, for the six years after 1859 the

broadside-rigged iron-clad, and for the ten or twelve years

after 1865 the central-battery rigged ironclad met, upon the

whole, with most favour at the Admiralty, it must not be

supposed that these types of heavy fighting ships were ever

without competitors. Captain Cowper Phipps Coles, who had been

mainly responsible for the cutting down and conversion of the

Royal Sovereign in 1862-64, was still a living and very active

advocate of the turret principle; and Mr. E. J. Eeed, who was

Chief Constructor from 1863 to 1870, while disagreeing with

Captain Coles on most points of detail, realised that the plan

of giving the maximum protection and the maximum arc of fire to

an armoured ship's heaviest guns was one which deserved the most

favourable consideration. Moreover, the battle of Hampton Koads,

in March, 1862, and numerous other actions during the Civil War

in America, demonstrated that, for work of certain kinds, the

monitor, or turret-ship, was a most useful and formidable craft.

Other ideas, also, were abroad as to the best

methods of compromising the claims of the various new factors

which, as time went on, seemed to demand inclusion in the ideal

fighting ship, yet which, it was amply evident, could not all

receive equal consideration. Very heavy guns were called for by

some; very thick armour was considered indispensable by others;

and while one party asked for a complete water-line belt,

another party urged the naval architects to devote even more

attention to the protection of the armament than to the

protection of the life of the ship. Yet other conflicting and

almost irreconcilable claims were put forward on behalf of high

speed, of great coal-capacity, of large sail-power, of lofty

free- board, of seaworthiness and steadiness of gun-platform,

and of small size, shallow draught, and comparative invisibility

to an enemy's gunners.

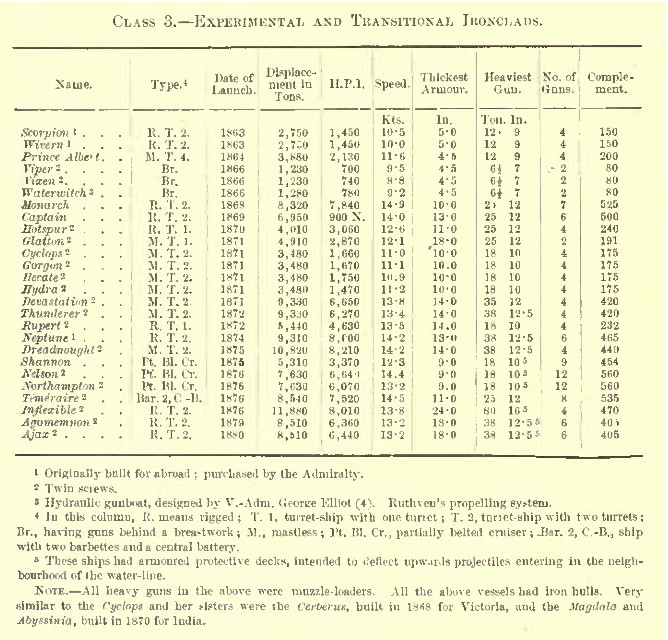

For

nearly twenty years these and other problems troubled the

minds of naval architects all the world over. In Great

Britain they led to the construction of numerous armoured ships

which are catalogued below. Some of them were not sea-going;

others, though sea-going, were scarcely fit, even in their best

days, for the line-of-battle; but they are all included, for the

reason that each one may be deemed to have contributed

something, if only a little, either to the development of that

type of heavy fighting ship which was generally acknowledged to

be the best at the end of the nineteenth century, or to the

establishment of certain doctrines which began to be accepted

about the years 1870-74, and which led later to the subdivision

of all new vertically-armoured warships into three definite

groups, viz., battleships, armoured cruisers, and coast-defence

ironclads.

26 CIVIL HISTORY OF THE ROYAL NAVY, 1857-1900.

The most interesting and significant ships in

the above list were the Monarch, the Captain, the Devastation

(with her two kindred ships, Thunderer and Dreadnought), the

Shannon, the Temeraire, and the Inflexible (with her smaller

cousins, Agamemnon and Ajax). It has been already pointed out

that in the ten or twelve years after 1865 the central-battery

rigged ironclad (class 2 above) met upon the whole with most

favour at the Admiralty as the best type of heavy fighting-ship.

The vessels in class 3

may be regarded as experiments in the direction of finding a yet

better type.

SEA-GOING TURRET SHIPS. 27

HMS Monarch |

HMS Captain |

HMS Devastation |

The Monarch,

designed under the direction of Mr. E. J. Eeed, embodied an

attempt to combine the advantages of a high-freeboard masted

ship with those of a turret vessel. In addition to her four

heaviest guns in the two turrets, she carried somewhat lighter

weapons under her raised poop and forecastle; and in that

respect she differed from previous British turret ships, each of

which had carried the whole of her heavy armament in the

turrets. It was a gain, of course, to be able thus to carry six

or seven guns instead of only four. On the other hand, the

raised poop and forecastle masked part of the fire from the

turrets, and so limited the usefulness of the powerful and

well-protected guns there. This defect constituted the Monarch's

great drawback. Her freeboard of 14 ft. made her a useful ship

at sea.

The Captain,

designed by Captain Cowper Phipps Coles, R.N.,C.B., assisted by

Messrs. Laird, of Birkenhead, was the production of an amateur.

Coles was strongly opposed to the high freeboard, which formed

one of the leading features of the Monarch. He desired a low

freeboard turret-ship, in order that she might present as small

a target as possible to the enemy. Curiously enough, however, he

reverted to masts and sails, and rigged his vessel heavily. Even

with her intended freeboard of 8 ft. 6 in., she would have been

unsafe in a heavy sea unless very carefully handled; but

unfortunately, owing to errors on the part of her designer, her

actual freeboard was but 6 ft. 8 in.

After having made

two cruises in the Channel, and having, by her behaviour, caused

some of her bitterest opponents to modify their opinion of her,

she sailed again with the Channel Fleet under Admiral Sir

Alexander Milne, K.C.B.; and, on the night of September 6th,

1870, during a south-westerly gale, she capsized in a fierce

squall, and went to the bottom, carrying with her the whole of

those on board except eighteen persons. The number of souls who

perished was 475, among them being her commander, Captain Hugh

Talbot Burgoyne, V.C., and her misguided designer, Captain

Coles. 1 This terrible

catastrophe condemned for ever the low freeboard rigged

turret-ship.

The Devastation,

and her successors, the very similar Thunderer and Dreadnought

(all of which were closely allied to the smaller non-seagoing

ironclads, Glatton, Cyclops, Gorgon, Hecate, and Hydra),

forestalled rather than profited by the dreadful lesson taught

by the fate of the Captain, for the Devastation was laid down

ten months before the disaster. The type was designed by Mr. E.

J. Reed, C.B. In it masts and sails were frankly and completely

abandoned, the result being the creation of some most successful

and safe low freeboard turret-ships. But in one respect the new

vessels were inferior to the Monarch. Though they possessed

all-round fire, they mounted only four heavy guns apiece, and

had no secondary armament whatsoever.

1

Proc. of C. M.: Parl. Paper 1871, 42.

28 CIVIL HISTORY OF THE ROYAL NAVY, 1857-1900.

HMS Shannon, armoured cruiser |

HMS Temeraire |

HMS Inflexible |

The Shannon,

with her larger but similar successors, the Nelson and the

Northampton, is interesting for more than one reason; although

the type was not a very successful one. The Shannon was not a

battleship, but she was intended to combine some of the features

of the battleship with those of the cruiser, and she was

specially designed for fighting bows on. Abaft her foremast,

therefore, she had a respectably thick armoured bulkhead with

recessed ports. Forward of this, there was no vertical armour;

but there was an under-water steel protective deck, curving

downwards towards the ram, and shielding the ship's vitals.

Abaft the bulkhead, as far as the stern, ran a water-line belt

of vertical armour, the lower edge of which touched the lower

edge of the protective deck; but, except the forward bulkhead,

there was no protection for the men at the guns, so that the

vessel, if regarded broadside on, might be called a partially

belted cruiser, while, if regarded bows on, she resembled a

central-battery battleship with an unarmoured bow. The

protective deck, as employed in the Shannon, was built into

nearly all subsequent British ironclads, and into all large

cruisers, whether armoured or not.

The Temeraire

marked a great advance, and embodied more than one

valuable new feature, though she was without the protective

deck, and had merely thin horizontal above-water plating to keep

out light plunging fire. Near each end of the ship, above the

upper deck, rose an armoured barbette, or open non-revolving

turret; and in each of these was a heavy gun, which fired over

the edge of the barbette and had a very wide command. The guns

in this case were so arranged as to disappear behind the

protection after their discharge, and to be revolved, and again

brought up to the firing position by hydraulic power.

Between these two

barbettes, with its guns on a lower level, was an armoured

central-battery, mounting six heavy pieces; and lower down,

along the entire length of the ship, was a water-line belt of

thick vertical armour. In this type, the biggest guns of all

were in two barbettes on the upper deck, above the keel-line of

the ship; and a strong secondary armament was in an armoured

box-battery between them. The design, due to Mr. Nathaniel

Barnaby, had in it the germ of ideas which a few years later,

entered into the normal and accepted battleship types of Great

Britain, the United States, Germany, Italy, and Russia, and to

some extent of France also.

THE FORCES OF

EVOLUTION. 29

The Inflexible

and her kindred were set-backs. Each of them had two very

heavily armoured turrets, placed close together diagonally

across the upper deck; and in each turret each had two very

heavy guns. Under and around the turrets, from the deck to below

the water-line, was a thickly armoured rectangular citadel,

forming the central third of the ship, but elsewhere there was