|

|

|

|

|

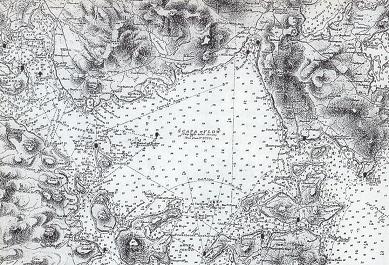

Detail

of an Admiralty chart, showing Scapa Flow and the

surrounding Orkney islands. This chart was updated

in 1924 when Cox began salvage operations and shows

the positions of the many wrecks he raised. Lyness,

on the island of Hoy, where Cox based his salvage

operations is far left. (Courtesy

- UK Hydrographic Office)

|

|

Ernest Cox poses for a London

photographer, immaculately dressed as always,

even when at work in the filth and squalor of

a sunken warship. He later said, "Without

boasting, I do not think there is another man in the

world who could have tackled the same job. Before I

undertook this formidable task, I had never raised a

ship in my life. Quite frankly, experts thought me

crazy, but to me these vessels represented nothing

more than so much scrap of brass, gunmetal, bronze,

steel etc., and I was determined to recover this at

all costs." (Courtesy - the Cox Family)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

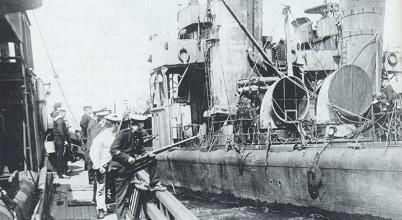

The German Imperial High Seas Fleet

interned in Scapa after the armistice in November

1918. Vice Admiral Ludwig von Reuter ordered their

crews to scuttle all seventy-four vessels rather

than hand them over to the Royal Navy. Here a Royal

Navy guard threatens a destroyer captain at gunpoint

to stop him from sinking his vessel. Altogether nine

unarmed German sailors were killed and fourteen

injured when the Royal Navy shot them, making these

victims the last casualties of the First World War.

|

|

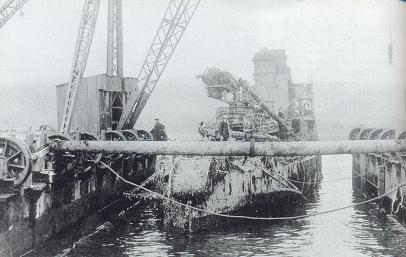

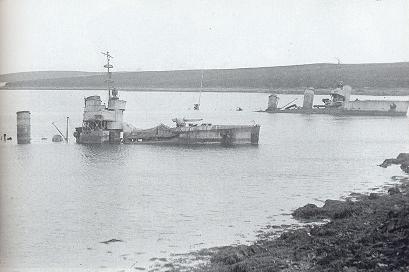

The

fast minelayer Bremse was one of the ships that the

Royal Navy tried to save when the fleet was

scuttled; to no avail. She ended up like this,

capsized and partially beached in Swanbister Bay on

the main Orkney island of Pomona.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

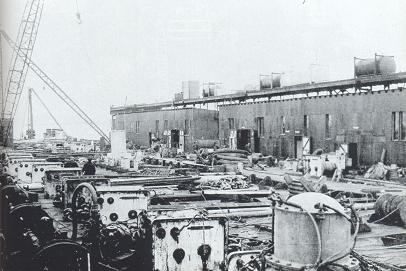

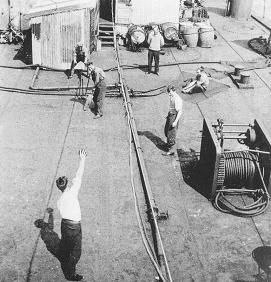

Looking

down a line of winches aboard one of Cox's floating

docks. The winches can be seen clearly in the

foreground where teams of men literally heaved a

sunken warship to the surface. The technique became

known as 'heaving twenties' because the men could

only turn their handles twenty times before needing

a rest.

|

|

A raised destroyer between the floating

docks during the 1920s, having just been dropped in

Mill Bay. Smit Salvage of Rotterdam used a similar

method nearly eighty years later to raise the

Russian nuclear submarine, Kursk, in 2001.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

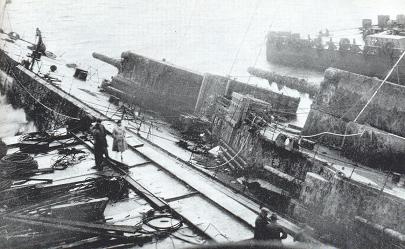

Two

beached destroyers waiting to be broken up in Mill

Bay. It took about one month to reduce them to scrap

metal. Each ship was methodically stripped down to

allow the vessel to float further up the beach on

the next high tide to be further broken up until

nothing was left.

|

|

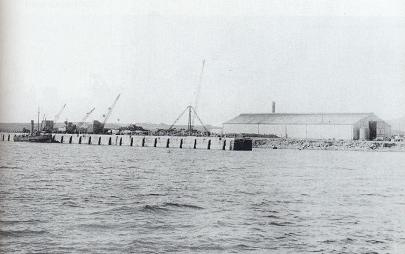

Lyness Pier as it was in the 1920s when

the salvage operations were well under way. Mill Bay

where the vessels were broken up, is on the right

and Ore Bay is to the left. The large crane that

killed Donald Henderson (a salvage labourer) is

in the centre.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

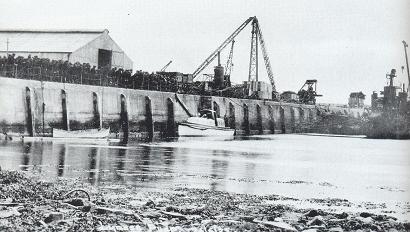

'Lyness Pier 24/6/25.' This picture is

dated four days after Henderson was killed when a

100ft jib collapsed on top of him. The crowds of men

on the pier are preparing to attend his funeral.

Loose wires can still be seen hanging down from

where the jib once stood. Cox's white pinnace is

moored alongside. She was named Bunts, after his

daughter, and no doubt conveyed him to Lyness Pier

for the funeral.

|

|

Sandy

Robertson (right) working as a diver's assistant to

Sinclair (Sinc) Mackenzie, standing on the ladder.

Sandy helped save Sinc's life after an accident on

the Von der Tann as well as that of Thomas McKenzie.

Sinc Mackenzie was the last diver to detect life

aboard the doomed submarine HMS Thetis in 1939. (Courtesy

- Sandy Robertson)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

Hindenburg heeling over to starboard on the first

attempt at raising her in 1926. Jenny Jack, Cox's

wife, is standing centre, facing the camera. A storm

is beginning to blow up that eventually led to Cox

losing the fight to raise her - this time.

|

|

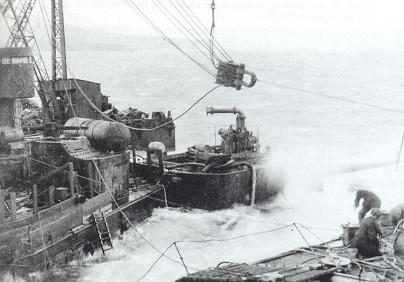

The storm that sank the Hindenburg on

the first attempt to raise her in 1926 as the waves

lashed the men and vessels trying to keep her

afloat. Cox's floating dock was holed, his pumps had

failed and his men were exhausted, but still he

fought the storm to hold on to his ship.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ernest

Cox, immaculately dressed as always, looking very

pleased as he stands on the bottom of a salvaged

warship.

|

|

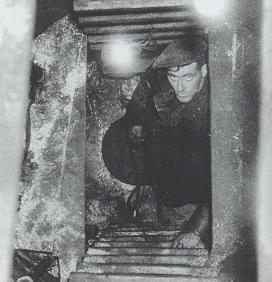

Jim

Southerland climbs down an airlock on his way to

work. The hatch was closed behind him and he climbed

down to the bottom hatch, knocking on it to let the

men inside her know that he was there. The airlock

was then pressurized to equal the air pressure

inside the compartment, and Jim would climb through

for his eight-hour shift. Jim

Southerland climbs down an airlock on his way to

work. The hatch was closed behind him and he climbed

down to the bottom hatch, knocking on it to let the

men inside her know that he was there. The airlock

was then pressurized to equal the air pressure

inside the compartment, and Jim would climb through

for his eight-hour shift.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

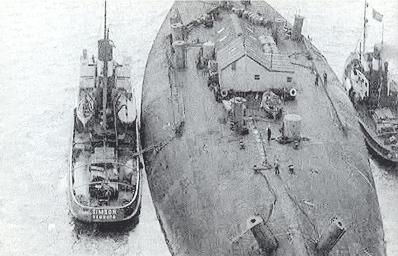

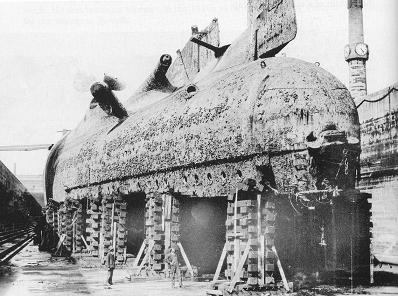

The

24,000-ton upturned battleship Kaiser shortly after

breaking the surface in March 1929. Men had to gain

access to the sunken warships' hulls through

airlocks. The four airlocks needed to enter and

prepare the Kaiser can be clearly seen here, looking

more like ships' funnels. In order to reach a sunken

ship, some of Cox's crudely built airlocks were 60ft

high.

|

|

The capsized Moltke en route to Rosyth,

surrounded by tugs. Through a misunderstanding two

pilots were appointed to guide her to the dry dock.

An argument over who should command her led to the

Moltke being cast off as she headed for the Forth

Bridge's central pillar, completely unassisted. The

temporary housing for men and machines while on the

journey was built on the ship's bottom, which was

now her top.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Adolph Hitler came to power a few

months before the Von der Tann was towed to Rosyth.

The Nazi Swastika flies over the tugboat Parnass on

the von der Tann's starboard side. Many sightseers

were in Rosyth to see Cox deliver his last salvaged

German warship. They were also among the first to

see this Nazi emblem in British waters, which six

years later would be a common symbol of evil

throughout the free world.

|

|

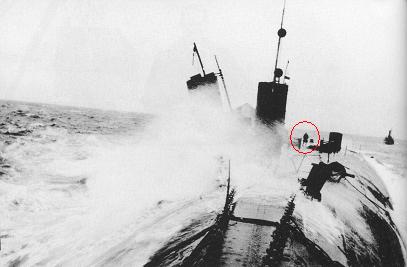

The

Seydlitz weathering the storm that struck while she

was being towed to Rosyth. She arrived there despite

the loss of both equipment and supplies in the

raging seas. (One of the passage or runner crew

circled)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A

'runner crew' of eleven to fourteen men took the

salvaged vessels the 270 miles from Scapa Flow to

Rosyth. In good conditions they could play cricket

on board, but they also weathered some terrifying

gales.

|

|

The runner crew aboard the Prinzregent

Luitpold pose for a picture in front of the

corrugated iron kitchen named the Hotel Metropole,

built on the upturned hull. Their sense of humour

could be seen everywhere. The mess and bunkhouse

were the Apartments de Luxe. The notice to the left

reads 'Honeymoons arranged, spring mattresses fitted

with speedometers. First aid equipment in all rooms.

Second class rooms no spring mattresses.' The menu

on the right reads, 'Boiled Luitpold with knobs on',

'Scapa salvage stew' with 'dock broth', Reporter

James Lewthwaite of the Daily Mail is in the centre

of the back row.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Seydlitz in her dry dock, ready for

breaking up. A sad end for a battle cruiser that

survived the Battle of Jutland and got back safely

to Germany in spite of damage from twenty-three

direct shell hits and a torpedo strike.

|

|

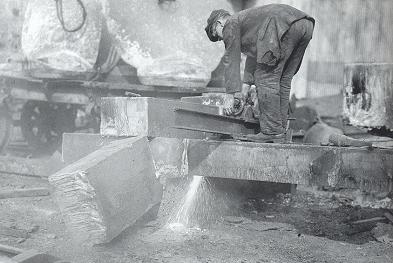

All the German warships salvaged in

Scapa Flow met the same fate. Sometimes their armour

plate was as much as 12in thick and was a great

source of revenue. Here a burner cuts the armour

plate into convenient chunks to fit into a furnace.

Behind him are propeller blades, which were also a

highly prized commodity from the wrecks.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cutting up Moltke. A burner at work.'

With no Health and Safety regulations, the burner,

with a cigarette in his mouth, cuts up the battle

cruiser with an oxy-acetylene torch. He was breaking

no rules in the 1920s as he stripped away metal to

lighten her for the voyage to Rosyth.

|

|

Thomas

McKenzie (Chief Salvage Officer) working at

his desk, probably aboard the salvage vessel Bertha,

after Cox left Scapa Flow and Metal Industries took

over. In June 1939 McKenzie led a team of salvage

divers to help rescue ninety-nine submariners

trapped aboard the sunken submarine HMS Thetis,

which ended in tragedy after his offer of help was

accepted too late. When the Second World War began,

like many of the Scapa Flow team, McKenzie worked

for the Admiralty Salvage Department, which

distinguished itself during the Battle of the

Atlantic and from D-Day onwards in Northern Europe.

He was eventually awarded the CBE and CB for his

work.

|