Arriving at the airfield

controlled by the British forces, we said our goodbyes,

thanks and good luck to our departing friends, the like

of which I shall never meet again. In next to no time we

were back in the arms of discipline. Instead of wanting

to discover our identities, we were paraded by officious

British Army sergeants and marched into a hut where we

were deloused by having white DDT powder pumped down the

backs of our necks, over our heads and up the legs of our

trousers. The whole experience was like becoming a

Prisoner of War all over again. I fully expected to hear

the familiar "Los! Los! ‘Raus!

‘Raus!" when we finally exited from that

building, looking like baker’s assistants covered in

flour.

We were then barked at,

to be told to find a trestle table, behind which would be

an N.C.O. who would register our identities and allocate

an aircraft number. When these numbers were put on a

large notice board, that would signify that the holder

could board the plane on the runway. But on the runway

there were no planes in evidence and there seemed to be

crowds of ragtail uniforms crowding the grounds. I found

the trestle table and the Army corporal began entering my

particulars into a ledger. He asked where I came from and

when I answered: "Plymouth", he remarked that

he came from Taunton, saying that we

‘Westho’s’ must look after one another. He

would put my name against a low number flight so I

wouldn’t have to wait too long to be on my way home.

Big deal. He also told me that there was another sailor,

called Venning, from Plymouth to whom he had given the

same flight number. Upon completing these formalities and

literally being set free to my own devices, it was time

to get my bearings about the place.

The first thing I noticed was that

there were no trestle tables laden with goodies, with

uniformed ladies imploring me: "Help yourself,

honey!" It seemed to be a case of find yourself a

billet for the night, listen for the call at meal time

and be prepared for that magic number to appear on the

large notice board. One thing I did observe was that the

last number on the notice board was far higher than mine,

but at the time I gave it little thought; perhaps certain

types of aircraft available had certain sets of numbers.

The meal towards the end of that day was a mess tin of

good thick stew, a packet of biscuits and my KLIM tin mug

filled with hot, sweet tea and I had no complaints.

During the next day planes came and

left with bodies who filed on board according to the

numbers on the notice board. And then the penny dropped;

the numbers were increasing in numerical order and there

was no sign of any lower numbers. Nor was there any sign

of Mr. Helpful when I went to a trestle table to be told

that my plane number had gone before I had even

registered! That meant re-registering with a higher

number and an even longer wait. Then I met Venning, whom

I recognised, but had not known his name. After

commiserating with one another he told me that he had

observed an aircraft standing apart from the runway with

its engines running and a fellow with a clipboard who was

obviously waiting for somebody. With nothing to lose, we

ambled over to the aircraft and enquired of the

clipboard-holder as to the chances of a flight. He was an

R.A.F. officer who had once served on an aircraft

carrier, so when we told him we were Navy, he told us to

stick around. They were waiting for two R.A.F. officers,

but if they didn’t arrive by a certain time, then

the places were ours. The waiting time was only going to

be a matter of minutes because of air traffic control,

but as we waited, hoping the two bods wouldn’t turn

up, those minutes seemed endless. Finally, with no sign

of the missing pair, we were told to scramble on board. I

ditched my French frying pan and my KLIM tin mug and,

together with my well-filled rucksack, was pulled up into

the aircraft with Venning close behind me. Even with the

aircraft door closed, it was some time before the plane

moved and all I could think of was the two missing bods

turning up and we two being bumped off. But it

didn’t happen, and we were U.K. bound.

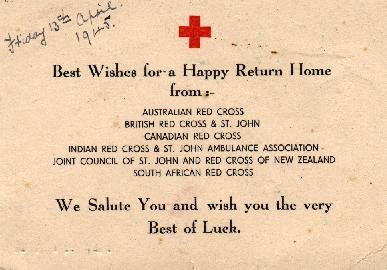

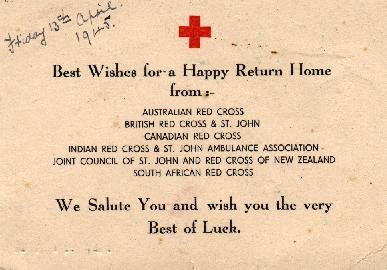

Card issued by combined Red Cross

organisations to released POW's, April 1945

he aircraft landed at a place called

Wing, where we were loaded into a covered Air Force lorry

and taken to a large house somewhere in London. Venning

and I had said we were Navy and somebody in authority

must have presumed that we were Naval officers. Upon

entering the building, I was asked my name, then a WAAF

orderly came to tell me that she was my orderly and would

show me to my room. The officer who had taken my name

told me to make the most of it and I would be handed over

to the Navy the next day. The WAAF orderly showed me to a

room and asked me if there was anything I wanted.

"Yes please. A cup of tea and a hot bath." In

no time she brought in tea and biscuits on a tray,

telling me that a bath was being prepared.

After a short while there came a knock

on the door; the orderly was waiting to show me to the

bathroom, and there was a white bath full of steaming hot

water! There was a large white towel, soap and a sponge;

so first I had a shave then, look out bath, here I come!

Stepping into that water, the temperature just right, was

a beautiful foretaste of anticipation. But no sooner had

I sat in the bath than I had to scramble to my feet again

in agony. The bones in my backside were protruding so far

that I could not sit on the bottom of the bath. It was a

case of kneeling, which was not so comfortable, but all

in all better than nothing and the hot water was so

pleasant, even to remove some of the DDT powder. Then I

had a look at my bare body and, boy, could I see bones! I

was thin, thin, where my muscles had gone and my knee

joints stood out like Indian war clubs. ‘Twas time

to abandon my good friends the pyjama trousers which had

served me well over those past months. What a story they

could tell in times of plenty of newspaper and those of

no newspaper. Goodbye, friends! I left them in a waste

basket. I searched the bathroom for cleaning gear to

clean the bath. A loud knock came on the door, then a

voice telling me that dinner was being served. I opened

the door and explained to the orderly that I could not

find any bath cleaning gear; she told me that she would

take care of that and was ready to show me the

dining-room.

There were not very many sitting down

to dinner and I must admit I was uncomfortable, sitting

at the table and being addressed as ‘Sir’ each

time I was asked after my particular likes. But it was

heavenly just the same. After the meal, about which I

remember very little, we adjourned to a bar, where we

were allowed two pints of beer, compliments of the RAF,

to welcome us home. The bath and the meal had made me

feel very tired, so I took a newspaper to my room and

turned in to a bed with white sheets - something about

which I had forgotten. I must have just about had time to

look at the newspaper headlines and then knew no more

until I was awakened by the orderly knocking on the door,

telling me that a cup of tea was outside and that

breakfast was ready whenever I chose. On reaching the

dining room I found that there were kippers for breakfast

together with, of all things, white bread! Wonders would

never cease. Venning and I sat together at the table and

after breakfast we were asked to report to the reception

room in the hall, where we were told that when we were

ready a car would be waiting to take us to Paddington

Station. Upon returning to my room to collect my

rucksack, blanket and greatcoat, I found the orderly

stripping the bed. When I thanked her for her assistance,

she replied that it was part of her duties. I asked her

if she smoked cigarettes and when she said she did I gave

her several packets of Camels. She took them and began to

cry, expressing her thanks. And as I said goodbye she

told me to hurry and put on some more weight.

Venning and I were then taken in an RAF

car to Paddington Station, where we were told that we

would find a Railway Transport Officer. Here at the

station entrance was a Naval Master at Arms who had

obviously been advised about us by RAF House. Now, being

clean of face, but oh so scruffily uniformed, we must

have left him wondering who we really were. But when we

began giving him our Naval service numbers he began to

laugh loudly, saying: "You pair of beauties have

been putting it over the RAF, pretending to be Naval

officers." Of course we hadn’t, but it had been

nice all the same. We were the first two ex-P.O.W.s he

had handled so, telling a Wren in the office to make tea,

he sat us down and asked us to tell him something about

when and where each of us had been put in the bag. After

some time he produced a Travel Warrant and Meal Voucher

for each of us, giving us the time of the train to

Plymouth. The train would leave from Platform 1 and we

bagged seats for ourselves and our packs, just sitting

there for a while, talking and slowly recovering from the

excitement of the past few days.

Whilst chatting we noticed that a pair

of red-capped Army policemen were walking up and down in

front of us, looking suspiciously at us each time they

passed. Venning quietly said: "We’re going to

have some fun here." Both of us was attired in

something resembling Army uniforms. I was wearing an Army

uniform and an over-large Army greatcoat, which was

nearly white from the DDT-spraying at the Army airfield,

and shod in American parachutist boots. Like me, Venning

was clad in a motley collection of clothing, also covered

in white powder; in addition, neither of us had had a

haircut for a long time. Those Redcaps just couldn’t

resist their curiosity any longer. One came to stand

behind us while the other stood in front of us, saying:

"Show me your AB 64s." In a put-on accent

Venning replied: "Never had one, old chap." An

AB 64 was a soldier’s identity book; not being able

to produce it meant that the Redcap had his hands on a

couple of deserters. He looked at me and made the same

demand. "Ich nicht verstehen," I said and the

fellow behind us said: "Blimey! He sounds like a

Jerry." Front Redcap told the other one to watch us

while he went to the RTO to phone for a wagon, whereupon

the other one came to our front, telling Venning not to

move and that the game was up. After a while Redcap

Number One came out of the RTO and the Master at Arms

came to the doorway and gave a thumbs-up sign. He called

to the other: "They are a couple of bloody matelots;

leave them alone." And so we were left in peace.

(What a lovely word that is; just let it blow off the

lips.)

We decided it was time to make use of

the Meal Vouchers so, collecting our bags, we went into

the station buffet. It being war-time we did not really

know what we expected to find on the menu, and anyhow a

Pusser’s Meal Voucher wouldn’t run to anything

spectacular. The buffet was empty except for an elderly

lady assistant and when she saw Venning and me, two

rather disreputable specimens of manhood, she could not

help but exclaim: "My Gawd! Where have you two come

from?" We showed the vouchers and explained that we

were returning Prisoners of War and please could we have

something to eat? "There’s nothing here good

enough for you boys," she said, then excused herself

as she walked out of the buffet, shouting for somebody.

She returned with an elderly porter and directed us to

follow him. He took us to the station staff’s

canteen and she followed, to tell everybody there that we

were P.O.W’s and were to be looked after.

No sooner were we seated than an

elderly lady came to us, stifling her tears, wanting to

know why we were home and not her son. Did we know him

and had we met him? What could have happened to him?

Naturally we tried our best to placate her, telling her

there was no reason why the lad wouldn’t show up at

any time.

Our packs were taken from us, and when

we removed our greatcoats there came a gasp as they saw

our uniforms hanging from our bodies. "Feed ‘em

up" became the order of the day, but of course we

could only eat so much and I believe we disappointed them

when they wanted to force so much food into us. There

couldn’t have been many of the station staff

available on the platform for a while because in no time

the canteen was filled with them, wanting to have a look

at us, ask us where we had come from and, the inevitable,

what was it like? Several cups of tea later, when we

seemed to have satisfied their curiosity, the first

assistant whom we had met came to the table and on it put

several pounds in silver coins. There had been a

collection amongst all the staff at Paddington Station

for Venning and me! Can you imagine how we felt? We must

have been the first of our kind to pass through the hands

of that crowd. We shook many hands, received many kisses

and "God bless you" when we went back to our

seat on the platform.

Tucked away near the entrance to

Platform One I spied a small confectioner’s shop.

Now that I had money I thought about buying a box of

chocolates for my Mabel. I went in as bold as brass,

receiving some strange looks from the elderly assistant.

Upon looking round the sparse contents of the shelves I

saw a large box of chocolates and, taking the money from

my pocket, said I would have the box. The lady brought

the box to the counter, quoted the price and said

something about so many sweet coupons. At the time I

really took little notice, busily counting out the amount

required, but with the money on the counter, she still

kept her hand firmly on the box and again asked for a

number of sweet coupons. I asked her what she meant by

sweet coupons; came the inevitable: "Where have you

been all these years?" When I apologised for not

knowing about coupons and explained what I was and where

I had been for such a long time, she gave a gasp and said

she would have to see what she could do about that. She

went to that same staff canteen to tell her story and

returned with more than enough coupons to cover the

amount required. Another "God bless you"

followed me as I left the shop with the box of chocolates

neatly parcelled.

We boarded the train which would take

us to Plymouth North Road Station, for onward transport

to the Royal Naval Barracks. During the long and tedious

journey we could not but help strike up a conversation

with a Petty Officer in our compartment; he had obviously

been burning with curiosity over our appearance and our

conversation about what to expect when we entered the

barracks at Keyham. Recognising us as sailors, he wanted

to know some of our history and then he worked out

roughly how much back-pay we might expect to receive. I

was told to expect an initial sum of one hundred pounds!

I must have lost my breath for a couple of moments as I

heard this - a sum beyond all expectation, and to be told

that this would be only an initial payment, with more to

follow.

And so the train finally arrived at

North Road Station and one of us telephoned to the

Officer of the Day requesting transport - only to be told

to hop on a bus. We were back in the Navy. I suppose if

we had said we had no money for bus fare we would have

been told to walk. So hop on a bus we did and arrive at

the barracks we did, to be told to report to the

gymnasium. I had visions of being told "Top of the

wallbars, go!" at the tender mercies of a Muscle

Bosun. But no, somebody in authority had ordered that we

be held incommunicado until debriefed sometime the next

day and the gymnasium was held to be a suitable isolation

post. As you can imagine, all the excitement of arriving

home had disappeared as we two specimens entered the

domain of the Royal Naval Barracks. Our entry was greeted

by a momentary hush, possibly due to their amazement.

Then a lieutenant said in disbelief at the sight greeting

his eyes: "What in the bloody hell are you

two?" All of my daydreams of arriving home had now

vanished; I don’t know whether I expected a brass

band or a handshake or a pleasant greeting, but after

four years of being Raus’d and Los’d, sometimes

at the end of a bayonet, I was to be put in isolation.

And this time I hadn’t stolen any Pudding-Pulver!

Venning and I just looked at one another, gave a shrug

and I said: "Just a couple of ex-Prisoners of War

obeying orders, Sir." He looked round to a couple of

P.T.I’s standing nearby and they shook their heads.

Obviously he had heard nothing about our orders and soon

came back down to earth. Asking us if we lived in the

Plymouth area and we affirming, he took us back to the

Officer of the Day and said we should be allowed home and

he would take the responsibility for us. He was the only

one to shake hands with us, took us past the guard house,

with instructions to report back to him next morning in

the gymnasium at nine o’ clock.

Remarkably, my Dad arrived outside the

barracks just as I was leaving - such a coincidence. Our

eyes watered as we hugged one another and together in a

taxi we went HOME. Once indoors, the first memory I have

is of seeing a large picture of my Mother, dressed in her

best cherry-coloured velvet dress and wearing on her

wrist a large watch, about which we had often teased her.

My Dad said: "Yes, I often sit and look at it."

And that was the best welcome home I could have wished

for. We talked and we talked about this and that. I

laughed when I heard that he had been shunted out of the

Police service; perhaps the incident of firing the rifle

helped; he was now employed in the Naval Dockyard.

I was pleased to be able to take off

all my clothing. Dad had carefully stored all my civilian

clothes and it was a delight to put on clean underwear,

shirt and trousers, which all hung from my body and made

him gasp when he saw the difference. I emptied my pack

and his eyes sparkled when he saw the packs of American

Camel cigarettes; there was rationing of almost

everything here. Even the pubs ran out of beer early each

evening. Next morning Dad woke me as he was going to work

and, after having a ‘K’ Ration breakfast pack,

I donned my bedraggled uniform and caught a bus to return

to barracks.

Once inside the gates, where the

guardroom was a hive of activity, I was stopped, goggled

at and asked questions. I really enjoyed the feeling of

creating such amazement. There I was, a bedraggled,

long-haired specimen, surrounded by neatly dressed,

uniformed members of the service, blancoed, belted and

gaitered, wondering how I could even enter the gates,

dressed as I was. It was most enjoyable and more than

compensated for the treatment of the previous evening. I

told the duty Petty Officer to phone the Lieutenant in

the gymnasium and in no time I was escorted there.

Obviously that officer had been making enquiries about

the incommunicado business because he worriedly asked if

I had spoken to any newspaper people and was relieved

when I told him I had only been with my Father. He

inspected me in a dubious manner but there was no way he

was going to smarten my appearance, in spite of the fact

that I was going to be interviewed by the Commodore of

the barracks at the first opportunity.

He took me to the Commodore’s

office. I was asked to be seated, coffee was brought in

and he asked for a résumé of my years in captivity. His

secretary was taking notes of the conversation and, when

I had given him the information he was seeking, I was

given a Commodore’s priority card, which for that

day would put me in the front of any queue I would

encounter. The first stop was the sickbay for a joining

routine medical examination. The Medical Officer could

hardly believe his eyes when I was stripped naked for the

exam. First, on the scales, where I hardly weighed eight

stone. I had also developed a harsh cough. As a result of

the medical, I was allowed to go on leave, with an

appointment at a certain date for a specialist

examination in the Royal Naval Hospital.

But first, just like that joining the

Navy routine, I had to be kitted out completely once

more. The priority card placed me at the front of each

line. My new kitbag, with the kit I did not require,

together with new hammock and bedding, all suitably

name-tagged, was put into the Long Leave store. Then to

the Pay Office to collect pay and Leave Pass. There was

some searching of ledgers when it was learned that my

last payment was in January 1941. And so, as the Petty

Officer on the train had forecast, I collected one

hundred pounds as a part payment, a Leave Pass for one

hundred and eleven days’ leave, plus double ration

coupons for that leave, authorised by the sick bay

because of my under-nourished frame.

The expediencies of war determined

that, instead of ditty boxes being issued to survivors

and new entries, small attaché cases would become part

of the kit issue. In no time Jolly Jack had found a

nickname for them and they were dubbed ‘Oggie

Hampers’. With my ‘oggie hamper’ I went to

the NAAFI canteen to see what was on offer in those

rationed times. Because it was nearing ‘Stand

Easy’, a large queue had formed, waiting for the

doors to open. The queue was controlled by a C.P.O.,

adorned in gaiters and belt as a sign of authority. I

went to open the doors and was promptly told by Chiefy

where to go, namely to the back of the queue - and

smartly at that. At this I produced the magical

Commodore’s Priority Card and, after a suspicious

look of disbelief, Chiefy opened the canteen door for me,

at the same time shouting to ‘stand fast’ to

the head of the queue, who must have thought that opening

time had come. Because of not knowing what was available

in the shops in town, I asked a lady server what was in

short supply. She queried why I was in the canteen alone

and when I produced the card again the Manageress took a

look and said: "Let him have what he wants."

Strangely enough, Brylcreem was considered to be the most

difficult commodity to obtain, so I was offered two jars!

With about sixteen weeks of leave ahead of me, I

purchased an ample supply of toilet essentials. The

ladies asked me why I was having such a long leave, and

there were lots of good wishes from them when they

learned the reason. Knowing that I had yet to purchase my

leave allowance of tobacco, I asked the ladies for a

brown paper carrier bag and that left space in the

‘oggie hamper’ for the tobacco.

Eleven a.m. was signalled by six bells

being struck and that was getting near ‘tot

time’, when the daily issue of rum was made. To

purchase my soap and tobacco ration meant that I had to

visit the main victualling store and - surprise, surprise

- I arrived just as the rum was being drawn from the

spirit store. This drawing of the rum, alas no longer

carried out, was a ritual supervised by an officer. The

rum was pumped by hand-operated pump into the measures

for the daily requirement. It has been known for an

unscrupulous pump operator to complete the pump action so

that the pump handle was partly on the up-stroke. With an

unsuspecting supervisor, the pump wielder had an amount

of neat rum at his disposal, the lucky sod - that is, of

course, if he could get away with it! On this day I was

an intruder to that circle, but as one says in the

service: "Act green, keep clean." I acted as

green as a new entry and showed my priority card to the

officer, who immediately softened in his attitude. In any

confined space like the spirit store in a warship or in a

barracks the opening of a cask of neat rum gave off a

strong heady aroma which, when permeating through a ship

via the ventilating system, caused the senses to develop

a hunger; thus one always knew when ‘tot time’

was near. I hadn’t had any liquor for many a year

and when that daily procedure was completed I was handed

over to the Supply C.P.O. He would sell me my ration of

soap and tobacco, as allowed for going on a normal leave

period. First question from him was: "Did you draw

your tot?" followed by: "How long is your

leave?" He was intrigued by the sight of the

priority card and when he learned the story and saw the

number of days leave allowed on my Leave Pass, he gave me

a tot of neat rum. With great bravado I gulped it down in

one draught, which was the recognised action when

consuming one’s tot. The next moment I had to sit

down, when that potent liquid hit my stomach! Generally

the consumption of the tot created two sensations: a

sense of bonhommie, where conversation abounded, and a

sense of hunger where one could "eat a horse and

chase the rider", as the saying goes. For me that

first tot after so many years took away all feelings from

my legs and I just sat there in a feeling of euphoria.

The Chief was talking away about the hardships of the war

but I didn’t hear a word he was saying. I believe

that if Feldwebel Weiblinger had walked into the room I

would have greeted him civily. Slowly, oh so slowly, my

body began to respond to my brain and I realised that the

Chief was talking about the soap and tobacco allowance

for the leave period. For up to fourteen days leave one

was allowed to purchase a half pound of tobacco and a

large bar of soap. Seeing that I had such a large number

of days leave, the Supply Chief suggested that the

allowance wouldn’t be enough and if I had enough

money I could purchase extra, which I did, filling my

‘oggie hamper’. He told me to leave my goods

with him and go to the dining hall for dinner, reporting

back at one thirty to collect and then proceed on leave.

At the dining hall I met Venning,

similarly dressed in a New Entry uniform with no badges

on the arms. At the door we were questioned by a gaitered

and belted Chief who, in all authority conferred by those

items of uniform, demanded in a voice that could be heard

at the barracks’ gates: "What are you and where

do you think you are going?" "Leading Stoker

Venning, going to have my dinner, Chief": answered

Venning. "Leading Stoker Siddall, going to have my

dinner, Chief": I parroted. Now a New Entry uniform

is described thus: it fits where it touches; if it’s

on the small side it will stretch in the wash; if

it’s too big the wearer will grow into it. In

addition, we sported no departmental badges or NCO’s

badges on our arms. Chiefy was ready to perform his act

of authority on this pair of loons until, like a music

hall act, we produced our leave passes and priority

cards. "Open Sesame". All he could counter with

was the time-honoured censure: "Get your hair

cut."

After tea in the NAAFI canteen and

collecting my rations of soap and tobacco, I went to the

Guardroom, through which one passed when going on leave.

Before I had time to show my leave pass a Master at Arms,

on seeing me, queried: "What are you then,

laddie?" I showed him my priority card and leave

pass and, after wishing me well, he ushered me out of the

barracks.

And so I had once more entered the

realms of society; I would be home for at least one

hundred and eleven days!

Almost forty years after my return home

I was given the following poem, written by a returning

‘Kriegie’. It sums up everything that a

‘Westho’ could feel at the end of ‘picking

‘em up and putting ‘em down’ when

approaching freedom road.

HOME-COMING IN

1945

Cliffs breaking thro’

the haze and a narrowing sea,

Soon will my eager gaze have sight of thee.

England, the lovelier now for absence long,

Soon shall I see your brow, hear a

skylark’s song.

Heart curb thy beating - there Channel cliffs

grow.

Eddystone, Plymouth, where Drake mounts the

Hoe.

Red of the Devon loam, green of the hills,

And I am home. God, my heart thrills.

Far have I travelled and great beauty seen.

But oh! Out of England is anywhere so green?

Thankful and thankful again as never before,

One of the Englishmen comes home to his

shore.

Anon.

(A prisoner of war on

returning home to Devon.)