Preface

I

have been asked, by our

friends in Guernsey, to extend

my earlier book on H.M.S. Charybdis.

Having commissioned her and

was with her to the end, I

hope I can fill in some gaps

in her history. My efforts may

not be flawless, but I write

in memory of a grand ship's

company and in recognition of

the bond between Charybdis

and the people of Guernsey.

The following is a summary of

the ship named CHARYBDIS.

Chapter 1

- Early Days

Cable

party preparing to slip anchor

.....

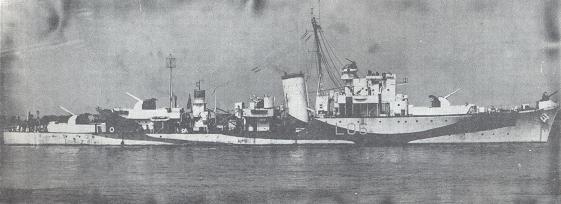

H.M.S.

Charybdis

primarily an anti-aircraft

cruiser, on the style of the

Dido class, commissioned at Cammell

Laird, Birkenhead on 15th

November, 1941. Her Captain

was Captain McIntosh whom I

was to meet again in later

years. From the very first day

of her commission the

Executive Commander, one John

Frances Whitfield, Royal Navy,

made it clear that Charybdis

was going to be a very

disciplined, if not hard ship.

I believe that in the first

six months we had a record

number of warrants read out.

The ship's company knew the

"articles" word by word.

Punishment was stiff, but at

least "keel hauling" had been

abolished.

Two

points of interest, Charybdis

carried in addition to her

Royal Marine Band, a Bagpipe

Band. This Pipe Band was

always in evidence at morning

physical training with the

Captain watching in approval.

Secondly, our ship's football

team which included a Bolton

Wanderers ex. pro.,

became champions of the Home

Fleet in March, 1942. No mean

feat with ships like the

Rodney (Flagship) and other

capital ships in competition.

The

day by day hum drum of her

"working up" period, prior to

her joining the Home Fleet at

Scapa

Flow, would make most

uninteresting reading except

the mention that she became,

by virtue of her latest type

radar, exceedingly rapid rate

of gunfire (16 round per

minute) and high speed, a very

efficient ship. An

efficiency that was to be a

saving grace to her in her

hectic times to come.

......

somewhere off the west coast

of Scotland 1941

So

it was, in her grey Home Fleet

colours, towards the end of

March, 1942 she sailed on her

first operation. This was as

main cover to mine-laying

operations at the Northern

Approaches. The work was done

swiftly and silently, and

although the enemy had

numerous surface forces

available, the mine laying was

successfully completed without

incident. It is difficult at

such an early stage of the Charybdis's

career to explain the close

comradeship of her ship's

company but it was evident to

me as on returning to base, Scapa

Flow, when in the Fleet

canteen some misguided crew

member of Rodney remarked

about the new light cruiser Charybdis

as the "Tiger without Teeth."

There was a spontaneous

reaction from the Charybdis

men, followed by a general

melee.

Repeated

exercises were carried out

inside the "Flow", which is

large enough to even allow the

firing - and recovery - of

torpedoes. These were still

the days of Fleets and it was

an impressive sight each

evening to watch, and listen

to the regulation “Sunset”

followed by a complete

black-out of the Fleet.

Then

in mid April, not that one

noticed the early Spring

in the Orkney's, it was side

parties to muster. After their

hurriedly painted work on the

ship's side we sailed,

completing upper deck and

superstructure in the colour

of our destination, en

route. The

colour

by which the enemy were to

call Charybdis

the "Blue Devil of the

Med.”. (Note: the

predominant colour of her

camouflage scheme.) On

the 18th April we joined the

Western Mediterranean Fleet

based at Gibraltar.

I

recall our first experience at

the Rock,

we were mainly classified as a

freelance cruiser. Lone

patrols were carried out

westward into the Atlantic, to

cover a south-bound convoy. On

the way back, make an attempt

to slip through the Straits -

in darkness - to test the

Garrison Regiment on the Rock.

On that occasion we were

straddled by 9 inch shells for

our troubles - full marks to

the Army. Then as the

situation deteriorated to the

East and Malta, Charybdis

was detailed to escort an

aircraft carrier carrying

fighter aircraft as far

eastward as was safe for the

carrier to fly them off, then

return to Gibraltar.

The

siege of Malta however

continued. The island was

already very short of

ammunition and fuel. Charybdis

continued with her calls of

duty. A search of the Atlantic

as far out as the Azores, for

an enemy surface raider. A

10 day fruitless search,

broken only by a short

refuel at the Azores.

Back to the Rock and surprise,

surprise, the harbour was full

- but our buoy in mid-stream

was still vacant. It was the

gathering of the Naval Forces

for the June vital convoy to

Malta.

There

were six supply ships, fast

merchant ships heavily laden

with the vital supplies the

Garrison of Malta needed. The

escort was strong – Malaya,

carriers Eagle and Argus, the

cruisers Kenya, Liverpool, Charybdis

and eight destroyers (close

escort) the anti-aircraft

cruiser Cairo, five large and

four small destroyers. (The

operation was given the code

name Harpoon and was commanded

by Vice Admiral A. T. B. Curteis

- flying his flag in the

Kenya.) The convoy slipped

through the Straits, in

darkness on 4th June, 1942.

Within hours the first "snooper"

enemy aircraft were on the

radar screen. But Fleet Air

Arm fighters kept a protective

screen around the Force.

Eventually the combined

attacks began, whilst our

fighters climbed to repel the

high level bombers, the three-engined

(twin torpedo) Italian

aircraft came in low over the

sea. All attacks were beaten

off, not without casualties

however, these were mainly

suffered by escort ships on

the outer screens. A destroyer

torpedoed and sunk, a heavy

cruiser damaged and had to

return to Gibraltar under

escort. A torpedo carrying

aircraft got through the heavy

barrage, and approached Charybdis

low on the starboard side. It

appeared to be making certain

of obtaining a hit, when a

single 20mm gunner got it in

his sights. The tracer and

high explosives shells went

directly into the centre of

the aircraft, which

immediately became a mass of

flames. Even so it dropped its

torpedoes, and these came in a

streak for the starboard bow

as the aircraft crashed into

the sea. I waited for the

torpedo to hit, but I was

amazed to see its track come

out on the port side. It had

passed directly underneath us.

Eventually

the Force and convoy reached

the approach to the Pantellaria

Straits. Here the carriers and

heavy units with their escorts

had to turn back. With no room

to manoeuvre, and the enemy on

both sides of the Narrows,

disaster would be certain. So

the A.A. cruiser Cairo along

with nine destroyers, four

minesweepers and six

minesweeping motor launches

took over the task of getting

the remnants of the convoy to

Malta. This depleted Force was

heavily attacked by two

Italian cruisers and its

escort of destroyers, Stuka

dive bombers, German bombers

and Italian torpedo bombers.

Despite

all the might of the enemy two

of the merchantmen were

escorted into Malta. The

supply ships were a relief to

the starving Garrison, but

only temporary. The enemy

started round the clock

bombing and strafing. It

appeared that Malta must

succumb. British submarines

made the arduous voyage from

Gibraltar to Malta carrying

essential medical supplies and

even cans of high octane fuel.

The two ultra fast minelayers

H.M.S. Welshman and Manxman,

both made lone supply runs.

Relying entirely on their high

speed they delivered food and

ammunition, etc., with the odd

bag of mail filling in any

vacant space on the upperdeck.

They were spotted and attacked

on every one of their

journeys, but their high

speed, excellent seamanship

and using darkness of night to

go through the Narrows, they

both achieved the object of

getting more supplies through.

Something

had to be done and so

operation ''Pedestal'' was

planned and the "O.H.M.S. or

All in a Days Work" details

more of this ship called

CHARYBDIS.

Chapter 2

– Operation Pedestal

(Note:

there a numerous

detailed accounts of

this massive, and

ultimately successful

convoy operation.

Readers are invited to

start with a

Summary

by Arnold Hague)

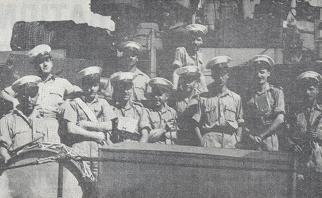

'B'

guns crew of Charybdis during

a lull

The

epic convoy, with its sea and

air battles, to Malta in June

1942, was over. Temporary

relief had been given in the

form of the two supply ships

being safely escorted into

Grande Harbour for the loss of

three destroyers and four

supply ships of the convoy.

H.M.S.

Charybdis,

a light anti-aircraft cruiser

based at Gibraltar, resumed

her normal role of "any task -

anywhere." The next few weeks

saw her escorting in turn such

ships as the aircraft carriers

Argus, Furious and the U.S.S.

Wasp in the ferrying of

fighter aircraft to Malta.

These carriers could only be

escorted as far as the Sicillian

Narrows, then

the fighters took off for

Malta. Enemy aircraft

opposition was always very

strong, with their bases only

ten minutes flying time away.

Indeed, many ferried aircraft

were shot down on route.

Returning

to Gibraltar after one such

operation, the normal routine

of fuelling, re-ammunitioning,

stores, etc. was interrupted

by an ever growing number of

warships. Destroyer

pens, cruiser buoys

and battleship/aircraft

carrier wall berths became

fully occupied. Rumours spread

around below decks. There was

one thing that was certain,

the gathering of the Fleet was

not there for any social

occasion.

On

the dark moonless night of

10th August, 1942 the Western

Mediterranean Fleet slipped

out of Gibraltar to join up

with the Home Fleet which had

come from the Scapa

Flow. The meeting did not go

unnoticed, and the Spanish

fishing boats duly made their

reports. At the following

dawn, after a night spent

decoding and answering light

signals, the Charybdis

found herself in very great

company. It was the largest

and most powerful Naval

force ever gathered in the

Mediterranean. Capital ships

included the battleships

Rodney and Nelson (16" guns),

aircraft carriers Indomitable,

Illustrious, Victorious, Argus

and Eagle. Cruisers

Sirius,

Phoebe, Charybdis,

Nigeria, Kenya, Manchester,

Cairo and 28 destroyers.

This powerful force with the

destroyers way out on the

beam, was ringed round a group

of 14 merchant ships which

were about to embark on

operation “Pedestal." History

was to be made by these

merchant ships, ships like the

tanker Ohio and the ships

loaded with aviation petrol,

ammunition and food, which

went through hell itself.

Steady

progress was made eastward,

and the objective Malta. Each

aircraft carrier her trailing

cruiser astern of her. It was

the trailing cruisers task to

give extra anti-aircraft fire

in the event of dive bombing

or low level air torpedo

attacks. Charybdis

was ordered to trail the

carrier Eagle for the whole

operation.

At

1408 hours on the 13th August

the enemy struck, Charybdis

resounded to 4 dull heavy

explosions. Eagle had been hit

by 4 torpedoes (Note:

fired by U.73) along her

port side. With the wheel hard

astarboard

Charybdis

avoided the Eagle who was

already rolling over to port

and sinking rapidly. The Eagle

had gone in 5 minutes, taking

with her over 800 men. But

amongst those saved was her

new Captain, our old Captain

McIntosh. (I

was later to serve with him

again on commissioning the

carrier Implacable in 1944.)

The

whole Fleet took evasive

action, and with warning

blasts of S - S from Charybdis,

the Victorious dodged two

torpedo attacks. Clear of the

sunken Eagle's position the Charybdis

put out her depth charge

patterns, but it was destroyer

Imperial who saw the U boat

surface dead ahead of her. A

single shot went straight

through the conning tower, and

the destroyer went on to ram.

On impact the destroyer sank

the U boat in a giant V. (Note:

Imperial was lost in May

1941. This incident refers

to the sinking of the

Italian Cobalto

by destroyer Ithuriel

later in the afternoon.)

The

battle was on - that night and

the following day saw further

submarine attacks on all

sides. Enemy air activity was

increasing but the fighter

curtain put up by the Fleet

Air Arm, broke up each

successive attack. It was fast

approaching a crucial point of

the whole convoy operation. The

arrival at the Pantelleria

Straits between Sicily and

the North African coast.

This

narrow sea passage was

entirely dominated by the

enemy, and it would be suicide

for any large capital ship to

attempt to force its way

through. Accordingly the Fleet

turned back westward and a

selected escort was chosen for

this final gigantic hurdle.

Rear Admiral Burrows a very

experienced tactician in the

Mediterranean Theatre of War,

was to be in command of this

small fast final escort. As

fate would have it, his

Flagship the heavy cruiser

Nigeria had been damaged by an

aerial torpedo so he

transferred his flag to the

destroyer Ashanti. At almost

the very moment that the Fleet

was to leave Force “H", so did

the enemies main air attack

commence. For the last two

hours groups of enemy aircraft

had been forming up on the

radar screens. Carrier based

fighters had been directed to

engage and break them up. But

the enemy bases at Sicily were

only minutes flying time away,

so fresh relays of bombers and

torpedo planes kept circling,

looking for an opportunity to

strike. The ships gunners had

to be constantly alert, now

and again two or three of the

enemy would break through, but

in the main they were forced

to drop their torpedoes out of

range. The enemy tactics were

wearing the men down, and

indeed the British pilots were

becoming exhausted.

Accordingly

with darkness now almost upon

us, the fighters started

landing on. At 1975 I saw the

last fighter land on

Victorious, then

in the faint night sky I saw a

group of black dots 1500 ft.

overhead. They started to peel

off, one after the other, in

vertical dives, I realised

they were J.U. 87's (Stuk8S)

and they were diving on the

carrier Indomitable. Though Charybdis

was too far away from the

Indomitable for our close

range fire to be effective, I

opened fire with the single

port Pom

Pom,

hoping the tracer would warn

Indomitable and her closer

escorts. Heavy A.A. fire

started at once but these Stukas

were the Luftwaffe's special

anti-ship dive bombers.

Indomitable received three

direct hits, and several near

misses.

Charydbis

steamed over to her at high

speed, and as we approached

she appeared to be on fire

from stem to stern. Smoke was

billowing out of her hangar

lifts and what I thought was

the flight deck, dripping

molten metal. (This was

actually blazing aviation

fuel.) The Indomitable was

temporarily out of control,

and Charybdis

circled her ready to go

alongside if need be. It

appeared that the Fleet had

been caught out by the Stukas

attack, but what was really

happening was that the enemy

was throwing everything they

had, and could at the Fleet.

Some 145 enemy planes, high

level bombers, dive bombers

and torpedo planes made low

level attacks. There were two

more casualties immediately.

The destroyer Foresight was

torpedoed and sank, and the

merchant ship S.S. Deucalion

was severely damaged by bombs,

lay stopped, and the destroyer

Bramham

was left to stand by her. Both

the Rodney and Nelson had near

misses, and the Victorious was

hit by an anti personnel bomb

on her flight deck. All ships

were twisting and turning,

whilst Charybdis

blasted away at every radar

contact approaching the

Indomitable.

Admiral

Syfret

in charge of the main force

was trying to organise some

sort of fighter cover for the

departing force “H” and the

convoy, as well as giving

extra cover to Indomitable,

whose loss would be a tragic

blow. But with the loss of

Eagle, Victorious unable to

fly off and Argus not suitable

for blackout take offs, no air

cover could be given. A signal

from Bramham

said S.S. Deucalion

had been hit by a torpedo and

blown up. It was not all one

way, 9 enemy planes were shot

down in this mass attack. To

the east force “H" was

approaching the Narrows, where

Rear Admiral Burroughs had

been told, lay

several U boats in waiting.

Though

it was now almost completely

dark, a group of 24 enemy

aircraft made a dive bombing

attack on the convoy. The

tanker Ohio was hit and set on

fire. S.S. Empire Hope

carrying canned aviation fuel

was hit by three bombs and was

soon blazing furiously. S.S.

Clan Ferguson, struck by a

stick of bombs blew up with a

horrific roar. The S.S.

Brisbane Star illuminated by

the flames of sinking ships

was desperately making maximum

speed, and rapid alterations

to course, but two bombs

struck her and she also lay

stopped, badly damaged. The

convoy was in real trouble

now, scattered by the vicious

air attack, depleted by the

withdrawal of Nigeria (and her

screen of three destroyers)

and with only the Kenya,

Manchester and Cairo in close

proximity, they were going to

be easy prey for the U boats

and E boat flotillas. Several

destroyers were scattered,

some standing by disabled

ships, others attempting to

get the surviving ships

together again. Suddenly the crusier

Cairo was hit by two or three

torpedoes and quickly sank.

This further depleted force

“H" and Burroughs signalled

Admiral Syfret

that his force was drastically

reduced. In consequence Syfret

signalled Charybdis

with her two destroyers, who

had been covering the gap

between both forces, to join

the convoy. Burroughs

indicated that Charybdis's

support was most urgent, and

that she should make every

effort to rejoin the convoy in

the shortest time possible.

This signal was followed by a

report that the cruiser

Manchester had been torpedoed

and sunk.

Captain

Voelcker,

of the Charybdis,

knew that time was against

him. He signalled his

destroyer that in his effort

to rejoin the convoy before it

was eliminated, he intended to

take the shortest route -

through a known enemy

minefield. His decision was

further endorsed when he heard

the cruiser Kenya report being

torpedoed in the bows. Charybdis's

luck held, and soon she was

passing the destroyer

Pathfinder who was searching

for Manchester survivors.

Within

minutes of Charybdis

rejoining the convoy her radar

showed surface craft

approaching at a rate of 40

knots. She warned all ships

and commenced her anti E boat

tactics. These defensive

tactics consisted of firing

broadside after broadside at

the approaching enemy, in a

creeping barrage, plus rapid

alteration of course. In this

way she could comb the

approaching torpedoes, in the

small amount of area to

manoeuvre and by pre-fusing

her shells, drive off the E

boats. Altogether 8 Italian

and 2 German E boats delivered

fifteen attacks and although

several were damaged none were

lost.

Now

the Admiral had only the

cruisers Charybdis

and Kenya (which had a damaged

bow) and a force of seven

destroyers, to meet the

Italian fleet, whose force of

six cruisers and 11 destroyers

had been reported steaming to

intercept the convoy and was

expected to engage at dawn.

The four remaining urgently

needed supply ships had to be

got to Malta. Soon another

action may be embarked on but

let us pause here and remember

the men on those supply ships.

They had seen other comrades

on floating bombs disappear in

columns of flame and smoke.

But still they kept to course

following the escorts as if

Fleet trained.

Aboard

the flagship Admiral Burrough's

face was grey and drawn with sleeplessness,

he knew that the testing time

of his life was probably at

hand. Soon he might have to

order 2,000 men to action with

the Italian fleet and most of

them would die. He would

almost certainly die with

them.

Worse

still his mission would end in

failure. After the warships

had made their fruitless

suicidal attack, and after

they had been beaten into

blazing wrecks the enemy would

sail in and finish off the

remaining merchantmen of the

convoy. Malta would starve and

fall to the enemy and he knew

what that might mean - at the

best victory longer delayed,

at the worst defeat.

Dawn

came and the convoy was

grouped in a diamond

formation. At the head of the

diamond was Rear Admiral Burrough's

on Ashanti, the four

merchantmen in the centre, Charybdis

on the port beam and Kenya on

the starboard and the

remaining destroyers made a

screen on each quarter.

Burroughs

signalled all units "engage

the enemy on first sight,

drive off at all costs, and

God Speed." Everyone was

looking on the horizon for

tell-tale smoke or signs of

the enemy masts. Aboard Charybdis

the men were weary but they

knew Malta was not far ahead.

There were no air or submarine

alarms now and somehow

it

seemed

like a lull before the final

storm.

The

lull was used to empty the

toilet buckets, feed off the

corned beef sandwiches, and

drink the lukewarm water. She

had been extremely lucky - the

Germans were later to call her

the Blue Devil - her

casualties were from shrapnel

and near bomb misses, but in

the main from fatigue.

Indeed,

fatigue was the hazard aboard

every ship in the convoy. If

the Italian task force

intercepted the convoy, their

superior fire power and

numbers would completely

destroy it. Admiral Burroughs

decided that the best defence

would be to attack. As Charybdis

was the only cruiser capable

of high speed she was ordered

to the van, have all torpedo

tubes ready, and ready use

shells fused at maximum range.

She would steam directly at

the enemy hoping to get some

salvoes in before the enemy’s

8" guns pounded her.

The

Kenya was to make her best

speed - about 15 knots -

approaching from the south

east, opening fire when in

sight, and irrespective of

being out of range. The

attempt here, to split up the

enemy force, hoping two

destroyers could get in a

torpedo attack. The remaining

destroyers were to make smoke

to cover the convoy, and

whilst the supply ships turned

away south, turn from the

smoke screen and join in the

attack. The situation looked

bleak.

Still

there was no sign of the

expected Italian fleet perhaps

there was hope yet. Somehow

the Italians had failed to

rendezvous with their kill.

Aboard the Italian flagship a

certain amount of confusion

was taking place. Mussolini

had instructed his Fleet never

to engage the enemy unless it

had air cover, fighter

protection. He had asked Kesselring

for fighter power, hut Hitler

was furious with the Italians

for their failure to destroy

completely the June Malta

convoy. So Kesselring

replied that the German

fighters were engaged as cover

for the German bombers. Indeed

the Luftwaffe had found the

convoy again. and

every effort was made to beat

off the attack. The Ohio had

now to be towed along by 2

destroyers, one each side of

her.

Meanwhile,

two R.A.F. Wellingtons had

located the Italian Force

dropping flares and bombs over

the fleet then, in plain

language, to send a signal

directing imaginary aircraft

to the scene. Several signals

were sent and these were

picked up by the Italians and

they decided, as they had been

denied air cover, that they

must abandon the attack on the

convoy. With less than an

hour's steaming from the

convoy the Italian Force

turned back to the north and

headed for base.

From

the very first report to the

British that the Italian fleet

had put to sea, our submarines

had been alerted. It was,

then, the submarine “Unbroken”

who lay in the path of the

returning Italian force. She

made a successful attack and

two heavy Italian cruisers

were sunk (Note: one heavy

and one light cruiser were

damaged). Other attacks

were made, and though no

sinking were

claimed, several Italian units

had severe damage.

So

for Force ''A” and the convoy

remnants, Malta came in sight.

The impossible had been done.

As the merchant ships entered

Grand Harbour to a tremendous

reception, Force ''H” wheeled

hard astarboard

and with a final farewell

signal, set course to cover

Ohio. But now Ohio had reached

a point where Malta based

fighters could protect her,

and she safely entered port.

Her Captain, Captain Mason was

awarded the George Medal. (Note

– George Cross.)

Steaming

westward Force ''H” could only

make 14 knots, the maximum

speed of the torpedoed Kenya.

The return journey to

Gibraltar was to be going back

through the hell of the

previous 2 days, with the

vital factor of reaching the

Narrows by nightfall. In

addition, the whole Force

consisted of men who had had

no sleep for three days and

two nights. The time was 0849

hours,

Malta was out of sight now

astern, and the sun beginning

to rise in a clear sky. On

board Charybdis

the order was "Stand to," she

had picked up aircraft on her

radar. The report "Boggies

on the screen" went out to the

accompanying ships, the

Luftwaffe had taken over from

the Italians. Charybdis

monitored the approaching

enemy aircraft, passing on

their formations and speeds,

to the remainder of the Force.

At

0905 hours the first of the

attackers came in. They were

JU 88's, twin engined

and carrying 1000 lb bombs.

They came in shallow dives,

out of the rising sun, three

or four planes attacking each

ship of the Force. As each

attack was beaten off, a fresh

wave came in. Standing on the

open bridge of Charybdis,

Captain Voelcker

himself gave orders down the

voice-pipe to the helmsman. He

would wait until he actually

saw the bombs leave the enemy

aircraft, before ordering hard

aport

or hard astarboard.

Twisting and turning Charybdis

was straddled, blasted by near

misses, and spattered with

bomb splinters. All the time

she kept up a terrific barrage

of fire, but as the attackers

were constantly diving out of

the sun from astern, the

forward guns could only engage

when the ship was on the turn.

Each ship of the Force was

similarly bombed, but

miraculously none received a

direct hit.

Attack

after attack came in, hour

after hour. Now a new threat,

ammunition was running low for

the aft guns manned by Royal

Marines, and their gun barrels

were almost glowing. Still the

enemy came in, diving more

steeply now as the sun climbed

higher in the clear sky.

Volunteers made up a supply

party, and carried shells from

the forward magazines to the

aft guns. For 8 hours the

enemy dive bombed Force ''H'',

with never more than a few

minutes between each wave of

aircraft. The ship's Padre

moved around the ship ignoring

the flash of guns, and blast

of bombs. An encouraging word

here, a bar of “Nutty" there,

his appearance - minus even

steel helmet - gave heart,

especially to the younger of

the ships company, and Charybdis

had boys of 17 in her guns

crews.

It

seemed that something had to

give. The situation aboard Charybdis

was getting desperate. and

no doubt the same aboard the

Kenya and the destroyers.

Either a bomb was going to

find it's

target, perhaps the guns

become overheated, or the men

collapse from exhaustion.

There was a possibility that

the main armament would run

out of ammunition. Despite the

fact that some 8 or 9 enemy

aircraft had been shot down,

the attacks were being pressed

home. The time was now 1720

hours, nearly 9 hours of

concentrated bombing. Ships

twisting and turning,

crossing each other's bows,

but defiantly remaining an

organised Force.

There had been casualties but

not one ship of Force "H" had

been hit. The clear blue sky

had held the bright sun all

day, and the enemy’s attacks

had become steeper with the

rising sun. It was then that

the unexpected thing happened.

A large black cloud came

slowly over the sun and stayed

there. Now the close range

gunners could quite clearly

see the diving enemy. They had

new heart and the barrage of

tracer and H.E. increased,

with aircraft falling in

flames. Suddenly the attacks

stopped and the radar screens

were clear.

Re-grouping

Force “H" with Ashanti at it's

head, steamed into the Narrows

as darkness fell. Every nerve

was strained, radar and asdics

sweeping constantly, for this

was the ultimate of enemy

traps - where only two days

previously the cruisers

Manchester and Cairo had sank,

with part of the convoy. Tense

and silently the ships slid

through, perhaps their 14

knots maximum speed helping in

their approach. The Kelibre

Light still swept the sea, to

the chagrin of the watchful

men. We knew that the Narrows

had been mined as the convoy

was taken through, and that it

would not have been swept

clear since. Also many new

types of weapons had been

used, such as the aerial

torpedo, which having failed

to hit a target then became a

mine. Charybdis

streamed her Paravanes,

and put her faith in God.

It

was with very heavy lidded

eyes that the lookouts and

bridge crew on Charybdis,

saw the faint light of dawn

astern. Suddenly the orders

"Stand to - Aircraft dead

ahead - Prepare to repel

aircraft." Just as quickly

rang the "Cease fire" bells.

The approaching aircraft

flying low over the sea,

waggled its wings, then

flew directly down the centre

of Force "H". Its pilot and

navigator waving like maniacs.

They were the first friendly

aircraft we had seen in four

days. The fact that they flew

such an antique plane as a Swordfish,

probably saved them from being

shot down.

"FORCE

H HAD REJOINED THE FLEET."

Next

came

the Bos'ns

Pipe, "the Captain will speak

in 5 minutes time." Captain Voelcker

then came on the ships tannoy,

saying we had rejoined the

Fleet - this for the men below

decks - and that before the

ship "Stood down," he had

asked the ship's Padre to say

a few words. I saw men slowly

slumping by their gun

positions, weariness and

re-action setting in but when

the Padre spoke, they joined

in - "Our Father Who Art in

Heaven."

More

Fleet aircraft joined the

welcome reunion, then

the whole Mediterranean Fleet

surrounded Force "H", and

under blue skies reached

Gibraltar. On arrival at Algerzerias

Bay, the Fleet slowly circled

whilst Force “H" entered

harbour, in naval traditions

an honour indeed.

The

following day was spent in

re-fuelling, re-ammunitioning

and preparing the dead for

burial at sea. Within 48 hours

Charybdis

was at sea again, as escort to

the carrier Furious, ferrying

fighters to Malta. the

journey to the Narrows and

back, was uneventful. Perhaps

the enemy were counting their

losses. Or debating how 2

cruisers - one badly damaged -

and 5 destroyers had managed

to get 4 supply ships to

Malta, past the combined Axis

forces.

Back

at Gibraltar again the Charybdis

had the first of her gun

barrel changes, the original

barrels completely worn out.

Some minor patching up was

done whilst "VOLUNTEERS" were

ordered to unload an

ammunition ship out in the bay

- as it was considered too

dangerous by the dockyard

workers to unload in harbour.

3

Chapter

3 - Convoys and Bay of

Biscay Patrols

Night

Action - 'Charybdis' bridge

personnel silhouetted against

'B' guns flash

So

then it was back to sea with Charybdis

slipping her buoy, and being a

"loner" steaming at 25 knots

back into the Atlantic. There

was a south bound convoy to

cover and part

of her duties were to

monitor the area around the

Brest Peninsular. The U boats

sailed from Brest, and were

often guided to convoys by

long range Focke-Wulf

aircraft. So when Charybdis

picked up a snooper

on radar, it knew that U boats

were in the vicinity. In point

of fact on this operation

there did appear on the

horizon an enemy four engined

F/W long range aircraft. It

shadowed Charybdis

for about 4 hours and at no

time dare it be risked losing

sight of. If there was any

cloud about then extra caution

was needed, because under

cover of a cloud the enemy

could, and did, swoop in a

surprise attack. After

a period of circling around

the enemy would be replaced

by a refuelled aircraft, and

so it went on. The

convoy was handed over to

South Atlantic forces, and Charybdis

was back at Gibraltar.

This

started a period of Bay of

Biscay patrols. Monotonous in

the extreme, these patrols

were always carried out alone.

The “Bay" is notorious for it's

storms of course, but it was

when the weather was foul that

Charybdis

was safest. Bad weather meant

that "snooping” enemy aircraft

was not about, and the 'U'

boats could not get a

periscope sighting. As

long as 8 to 9 days at a

time were spent on these

patrols, sometimes with a

little drama thrown in.

On one such patrol the sea was

like glass, with a clear blue

sky. Dangerous conditions and

Charybdis

took to a zig

zag

course, and an increase in

speed. Sure enough the radar

picked up an approaching

aircraft. When it came in

sight over the horizon and in

answer to the challenge, fired

two "Very" flares, we closed

up at action stations -

because the flares were the

wrong colour. The enemy

circled for a while, then

decided he had bluffed us.

Still cautious though,

remaining at just about our

maximum range. Eventually he

came that little bit closer,

and we sent off four salvoes.

As soon he saw the flashes he

went into a dive, and our

shells burst exactly where he

would have been. He now knew

that he had been identified,

kept out of range and no doubt

was sending out signals to 'U'

boats in proximity.

We

now had a second radar echo.

This aircraft came in sight

and was immediately recognised

as a Sunderland Flying Boat.

By Aldis

Lamp we put the Sunderland in

the picture. She flew away

until she was almost off the

radar screen, then turned back

to catch the enemy unawares

from astern. To our delight we

saw the enemy aircraft go down

in flames. Such little

co-ordinated successes

brightened the weary routine.

Our

allocated patrol time

completed, we would return to

the Rock. The sight of which

was now becoming a bit of a sickener.

Whilst re-fuelling went on,

fresh stores were loaded,

ammunition topped up, and

selected parties sent ashore

to work inside the Rock.

Gunners went to a special

''Dome'' training, there was

always a

certain bitterness

about this, and the Officer's

in charge knew it. After days

and days of the real thing, to

see it on a screen was as bad

as being told they were not

doing their job properly. So

these ''Dome'' visits were

made as brief as possible, and

a brisk walk around the town

substituted. One could have a

complete change, not by

choice, in becoming a member

of the "selected party" for

working inside the tunnels of

the Rock. Here the Charybdis

men worked knee deep in water,

hauling 3in electric cables

along for the R.E.'s.

This was not a punishment for

no offences had been committed

rather, I think, it was an

incentive to make men glad to

get back to sea.

Chapter

4 - Operation Torch, French

North African Landings

Having

done three days working

inside the Rock, whilst

others painted ship, cleaned

out the bilges, and all the

work that goes into running

a man o' war. It was

noticed that the harbour was

starting to fill up again. More

destroyers

and cruisers, oilers

and submarines. Another

Malta convoy? Mess

deck “buzzes" were very strong

in that belief. On the evening

when it seemed that not

another single ship could find

a billet in the harbour, a

conference of all ships

Captains was held in the Wardroom

on board Charybdis.

This closed at 2300 hours. I

was “Key Board Sentry" for the

middle watch, a duty normally

reserved for the R.M.'s

(perhaps they had all been 'at

the Conference,) to this day I

do not know why I had that

particular duty. I remark on

this because I was able to see

the number of high ranking

officers, and sense the

general tension.

When

we sailed the following night,

again selected because there

was no moon, we were told our

objective - the North African

landings. Whilst the Americans

were to take Casablanca, the

British had to take the

Mediterranean ports, with Charybdis

covering the toughest of them

all, Algiers. Charybdis

circled her flock of

troopships, getting them in

line and order of approach.

That done and an order for

complete radio silence, with

all ships blacked out, she

positioned her allocation of

destroyers on the beams. Much

depended on the element of

surprise. If undetected,

Algiers and its valuable

harbour could be taken,

without too much fighting. If

we were observed, then a

destroyer with Commando's

aboard was to be sent in at

high speed - burst through the

boom defence - and ram the

main jetty, bows on. The sea

was moderate, not unsuitable

for Infantry Landing Craft,

and Charybdis

leading the Algiers expedition

closed in on the harbour

entrance. This entrance had

heavy artillery batteries on

each side, capable of giving a

covering cross fire. As the

Force silently, and now at

about 8 knots crept towards

the entrance, the lights of

vehicles moving along the

waterfront - and the town

itself well lit up - reminded

me that it was the first port

I had seen with lights on for

a long time.

Suddenly

portside of the boom a light

was flashing a challenge. The

game was up, there was no

point in Charybdis

attempting a bluff reply from

a blacked out ship.

Accordingly rapid fire was

opened up on the harbour

batteries, whilst the

destroyer increased speed to

ram through the boom. As she

smashed her way through, we

saw the lights of Algiers

going out fast. The batteries

were soon silenced, and the

destroyer having rammed the

waterfront, had landed her

Commando's. Fighting continued

throughout the night, but at

dawn Algiers had been taken. Charybdis

now escorted the empty

troopships westward passing

them over to destroyers in the

Straits, and putting into

Gibraltar herself. Here she

quickly re-fuelled, took on

all the new Allied currency

some millions of £'s worth -

in notes to be the official

money in North Africa, in

place of the franc, German

mark and Italian lire. Re-ammunitioning

was completed in record time,

and Charybdis

returned to Algiers at high

speed.

We

went alongside the battered

jetty at Algiers, and off

loaded the new currency. There

was still some resistance

around, and sniping was taking

place from roof tops. I recall

a group of war weary 8th Army

men winkling out these

snipers, putting their heads

into our mess deck portholes

and asking if we had anything

for them to eat. We had a

stack of “Herrings in", which

somehow had not found their

usual destination - over the

side - and these the 8th Army

men seized with delight. We

all agreed that they must

have, indeed, been hungry.

On

leaving Algiers we were

ordered to proceed east, and

give support to the attack on

Bizerte.

There we found monitor H.M.S.

Roberts (15in guns) well in

shore, and blasting her shells

inland. About 1600 hours our

radar detected a very high

flying aircraft, a "reccie"

plane, always

an obvious sign of

imminent danger. Sure enough,

at dusk in they came. Spread

out, low over the water, came

some 20 to 25 enemy torpedo

planes. Charybdis

immediately increased speed

and twisting and turning, went

to meet the enemy formations.

She opened fire as soon as

effective range was reached.

At least 6 torpedoes were

dropped at her, whilst the

other aircraft tried to get

round to the Roberts. The

Roberts seeing she was about

to be attacked, sent an urgent

signal to Charybdis,

pointing this fact out. There

was a temptation on the bridge

of Charybdis

to signal back "we are not

having a tea party either,"

but as it so happened

the Roberts was safe. Being

designed and built as a

Monitor she had a very shallow

draft, to enable her to get

close inshore to bombard.

Normal set running torpedoes

could not hit her and, in

fact, none did.

Eventually,

after some routine work along

the North African coast, which

included covering a large

convoy of troops

ships, in company with four

other Dido class cruisers,

forming the 10th Cruiser

Squadron under Rear Admiral Vian.

A word

here on Rear Admiral Vian,

of the the

Cossack fame. He was

flying his flag Euryalus,

and with a touch of his “the

Navy's here" he signalled the

Squadron to "Line ahead."

Steaming at full speed we

swept straight down the centre

of the troop ships, it must

have been a re-assuring and

impressive sight for the

troops. Well, eventually the Charybdis

did the inevitable, she

returned to Gibraltar. If

Gibraltar had been a grim

place before, it was even

worse now. With the surge of

more Navy ships, and Americans

included, the place was "dry"

with the prices of everything

trebled. However, this time

the Charybdis

men were not required to

"volunteer" for work inside

the Rock. Re-fuelling etc.

completed, we were wondering

what was next on the agenda

when a boat came alongside -

loaded with mail, from the

U.K. This was loaded with

glee, and unrealised energy.

Next, as an infantry landing

craft came alongside loaded

with enemy P.O.W.'s

Commander Whitfield, Royal

Navy - our Commander announced

over the tannoy

that there "must be no

fraternizing with the

prisoners." That announcement

created the biggest roar of

the whole day, aboard. The

enemy P.O.W.'s

were blind-folded as they came

aboard for security reasons,

and consisted of Italian Naval

personnel, and air crews of

the Luftwaffe. They were

escorted and that is the only

word to describe it - up the

companion way - to the ship's

company ''Rec

Space." Here our Royal Marines

took up guard duties.

Chapter

5 - Atlantic, Home Waters,

Russia?

So

we slipped our buoy joyfully,

and as darkness fell steamed

alone out into the Atlantic.

It did occur to me that, if on

this trip we should be

attacked in anyway, then our

enemy’s comrades would share

the pleasure. Our course was

set to cover a north bound

convoy of ships, in ballast,

and so for the first day we

steamed W/Nor/West. For the

time of year the seas were

relatively moderate. As usual

Charybdis

did her "daily orders," clean

flats, heads, mess decks, the

Royal marine barracks area,

the galley, the sick bay -

very few de-faulters

- but a queue of "Request men"

- all with their own ideas of

hopeful extensions of leave. A

warship of the Royal Navy has

a regular standing party

throughout it's

commission, and it was these

men who were requesting long

overdue leave. De-faulters

dealt with, the

"Requestmen"

were told each case would be

dealt with on it's merit, on

arrival at U.K. There were

some unhappy faces, however,

at the start of this steaming.

The men of

all ranks, who were still

under stoppage of leave.

Here again the Captain

endeared himself to the ship's

company by having the Bosun's

Mate pipe over the tannoy

“the Captain will speak in 5

minutes time." When Captain Voelcker

did speak it was with his

usual calm voice, to say that

all men under stoppage of

leave from Mers-el-Kebir,

could consider it cancelled. I

would like to think he heard

the roar of applause.

Steaming

through the early hours of the

night, we found the wind

rising rapidly. By the morning

watch it was blowing a Force

9. As we were now heading

north into the Bay of Biscay,

all normal storm routine was

put into being. Nobody was

allowed on the upperdeck,

any movement from for'ard

to aft, or vice versa was via

below decks, with the

immediate closing of

watertight doors en route. By

the forenoon it was blowing

Force 10 and although the

ship's engines were doing

revolutions equal to 15 knots,

the ship was just keeping her

head into the seas. She was

doing some very uncomfortable

"pitching," burying her bows

deep, then rising high only to

plunge again. The routine of

the ship was carried on more

or less as normal except for

the galley where, of course,

restrictions in the use of

boiling water and other hot

liquids had to be taken, in

view of the motion of the

ship. But the P.O.W.'s

found life aboard a Royal Navy

cruiser distinctly

uncomfortable. The Germans

were very ill, as were the

Italians, but in typical

Teutonic fashion, the Germans

ordered the Italians to attend

to them. We left them all to

get on with it.

As

the storm persisted our

progress was slow, but at

least there was no danger from

'U' boats or aircraft. Finally

it blew itself

out and whilst increased

defensive precautions were

taken, so the upperdeck,

etc. became usable. The

checking of the security of

boats, cranes, ready use

ammunition lockers - all that

part of the ship pounded by

the sea - and the recommencing

of painting ship, which was

only ever interrupted by bad

weather, or the enemy. On this

occasion of the "carry on

painting" the enemy were to

join in, but not as planned by

either side. The P.O.W.'s

were brought on to the upperdeck,

under armed guard by our Royal

Marines for exercise, as

according to their rights. One

arrogant Luftwaffe pilot,

complete with Iron Cross, was

explaining by hand language

how he had dive bombed Charybdis

in the past. The angle of

approach, his speed, how his

bombs had dropped alongside

when a large pot of dark grey

paint fell from above just

about covering him, apart from

his boots. It was explained to

the senior German Officer in

charge of the P.O.W.'s

that accidents of this type

did occur when ship's funnels

were being painted - and one

should not stand in close

proximity when the ship was

underway.

There

were no interruptions on the

remainder of the passage, and

we were signalled to proceed

to the Mersey Bar. Here night

leave was granted to one

watch, whilst our docking

details were sorted out. It

turned out that there were no

docking facilities available

for Charybdis

and she was ordered to Vickers

Armstrong, at Barrow in

Furness. We arrived there on a

Saturday, and went up the

river to the dockyard.

Apparently there was a big

rugby match on locally and as

the road bridge was swung

open, hundreds of fans gave us

a great welcome. It was grand

to be back in England, even in

December everwhere

looked so green and fresh.

Once

we had docked the first leave

party were away, on a leave

which was long, long overdue.

Some of the ship's company had

Christmas at home,

I had my first for 4 years.

The second leave party had the

New Year. The town of Barrow

was a very hospitable place,

and great nights were had

ashore. The comradeship aboard

Charybdis

was such that no man need be

short of anything when going

ashore, whether it be

money, smokes or any gear for

a special date. There was

never any trouble, and the

strange thing is that although

it was mainly a ship/submarine

building town, and many fine

ships were built there, when I

revisited the town some 15

years later, many people

remembered the Charybdis

with pride.

6th

March,1943,

all too soon our damages had

been repaired, and came the

day when again the road bridge

was opened for us to go down

river. The banks of the river

were massed with people for at

least a couple of miles. Many

W.R.A.F.'s

crying and waving their

handkerchiefs. I recall the

Commander having the "Pipe"

made, "Clear lower decks, fall

in for leaving harbour" adding

"take your last look at Barrow

in Furness." For the majority

of the crew this was to be

only too true. Whilst in

Vickers dockyard we had been

fitted out with upperdeck

steampoints,

to couple up steamhoses

for de-icing, and below decks

all piping had been lagged.

Also we had been issued with

balaclavas and other

protective clothing. It was an

automatic presumption then,

that we were detailed for

Russian convoys.

Well,

Charybdis

had proved herself in the

Mediterranean and whilst I do

not think anyone aboard was

thrilled about fighting in

Arctic waters, there was an

air of confidence. So there we

were, back at Scapa

Flow, back with the Home Fleet

- it couldn't be only 12

months since we anchored

there? It seemed years ago,

and I believe that even the

youngest members of the ship's

company had aged 5 years in

that time.

Scapa

F1ow was still Scapa

Flow, desolate at this time of

year, swept by gales and bleak

indeed. It was impossible for

the ship's boats to take Libertymen

ashore and many times the

"Drifters" - small trawlers -

could not come alongside. The

only shore facilities in any

case were the Fleet canteen,

and it's

entertainment stage. Here

again the Navy showed it's

versatility, some of the

comic's and singers would

have, with a little training,

swept the variety show

business. We began to compare

the advantages and

disadvantages between Scapa

and Gibraltar. Scapa

was dismal,,

cold and boring but mail was

fairly regular and IF one

could get ashore, then there

was entertainment.

At

Gibraltar it was warmer, just

as boring, little or no

entertainment and mail very

erratic. I think the

inactivity of Scapa

finally swung the vote and

when, one early morning we

again steamed out of the Flow

to find our course set south,

it was with relief to get the

“Buzz" that we were heading

for our happy hunting ground,

the Mediterranean. With

regards to the de-icing gear

fitted, we were flattered to

think that if the Home Fleet

could not cope with the Russian

Convoys, they could always

send for the "Blue Devil" of

the Mediterranean.

The

sea welcomed us back into its

arms with a raging storm, and

we took a fierce battering. We

had to put into Milford Haven

to put ashore a casualty from

the heavy seas. No doubt the

sea was testing the ship to

make sure she was in condition

to retain her title. So the

Rock came in sight, and there

we were back at our old buoy.

Many small operations followed

our return, both up the

Mediterranean and out into the

Atlantic. The westward

sailings were similar to the

one when we lost our senior

diver, and had three men

seriously injured. That was a

tragic happening, because the

enemy was not directly

involved. On this particular

patrol we were again

experiencing very bad weather,

with huge seas running. The

starboard whaler's bowline had

come adrift, and the order to

take it inboard was passed by

'phone to the Captain of ''B''

guns. He in turn ordered

Leading Seaman Mylott,

and three Able Seamen on to

the fore'stle.

Charybdis

was "shipping it green" at the

time, and just as the men got

for'awd,

her bows plunged into another

mountainous sea. When she

reared up and the water fell

away from her, it was seen

that the L/S had been washed

over the side, two of the

A/B's were flung against the

centre capstan, badly injured,

with the other A/B

miraculously still clinging to

the guardrail. The last I saw

of the very popular L/S was

his hands held high, as he

rapidly disappeared astern.

There was nothing anyone could

do, it was impossible to lower

a boat away,and

in any case no man could

survive more than a few

minutes in those seas.

That

L/S had been an excellent and

courageous ship's diver. Many

times when Charybdis

had been tied up at her buoy

in Gibraltar harbour, and

Italian midget submarines had

found their way in to plant

limpet mines on ships keels,

he had gone over the side,

searching the ship's hull from

for'awd

to aft. On anyone of those

dives the mines could have

exploded, yet he always came

up his usual cheerful self.

His loss was felt deeply by

his shipmates and it should be

recorded here, that in true Naval

tradition, his kit was laid

out on the quarterdeck to be

sold by auction. An offer was

made for example, one

seamans

collar, the price paid - then

the said collar was put back

with the rest of the kit, for

further offers. Invariably the

sale of certain non personal

articles were sold several

times, then

accepted. The monies then

collected, plus the man's

personal possessions, were

forwarded to the next of kin.

Chapter 6

- Famous Men - Escorting

Winston Churchill

Having

completed another Bay of

Biscay patrol, at the same

time covering a homeward bound

convoy, we were signalled to

go into Plymouth to re-fuel.

We lay in Jenny Cliff Bay, our

usual place near the

breakwater, and remaining

under sailing orders.

Charybdis

was to escort R.M.S. Queen

Mary, with the Prime Minister

Churchill and the Cabinet, to

New York. Picking up the

''Mary'' off the Northern

Ireland coast we proceeded

westward at high speed. The

weather deteriorated rapidly,

and within hours Charybdis

was awash from stem to stern.

Below decks on the forward

mess deck the water was knee

deep, as the heavy seas found

the damaged "plates" from bomb

near misses. As the 84000 ton

Mary was still carving her way

at 32 knots, an urgent signal

was sent that Charybdis

could not maintain that speed

in the sea conditions. The

Commodore R.N. flying his flag

on the Mary,

replied that as still in

dangerous waters he would have

the Mary take a zig

zag

course - the Charybdis

must take the direct course -

and maintain high speed. The

cross Atlantic trip was not

very comfortable but the men

were cheery, for a run ashore

in New York would be very

welcome after Gibraltar and

the western Mediterranean.

Six

hours steaming and the Charybdis

safely delivering the Mary to

it's

passengers historic meeting,

when there was a radar contact

ahead. First the "Challenge"

then as the American

destroyers hove into sight, a

signal from the Mary - "Thank

you, well done, return to base

and good luck." Charybdis

had a fine Captain in the

ex-submariner Voelcker,

and he sensed the feelings of

his men. He ordered course set

for Plymouth - and an urgent

request to the C-in-C for

boiler cleaning. The request

was granted, and Charybdis

at last passed the boom of her

home port and lay in Jenny

Cliff Bay - from where she was

later to sail for the very

last time. She and her weary crew,

had a four day break at

Plymouth. For the members of

the ship's company who came

from the North, Wales,

Scotland, Northern Ireland and

the North East it meant just a

few hours, but to every man

the Captain had achieved the

highest respect.

...

Carrying a Gracious

Passenger, Noel Coward

Another

Bay of Biscay patrol,

escorting a convoy and return

to Plymouth where we

re-fuelled and took on a

passenger - Noel Coward - who

we were to take to Gibraltar.

I insert extracts from Noel

Coward's Diary:

"It

feels strange to be starting

off again and leaving England

behind. I hope I shall get

through these various journeyings

safely because I do so much

want to see the end of the

war. The familiar Naval magic

has already taken charge of

me, I wander about, clamber up

on the Bridge whenever I feel

like it, stamp up and down the

Quarter Deck, have drinks in

the Wardroom and make jokes

and feel most serenely at

home. This is unquestionably a

happy ship. I felt it

immediately when I came on

board with the Captain this

afternoon. He is a nice man,

and has the usual perfect

manners of the Navy. He has

turned his cabin over to me as

he will of course be using his

sea cabin during the voyage. I

am looked after by his Steward

who is also typical, having

been in the Service most of

his life except for a few

years before the war when he

retired. Now he has been

yanked back again and seems,

on the whole, to be more

pleased than not. He has what

we would describe in the

theatre as a "dead pan" but

there is a glint of humour in

his eye.

I am

an honorary member of the

Wardroom and am to take my

meals there which will be

gayer than sitting in lonely

state in the Captain's cabin.

The ship's officers seem to be

a good lot, mostly quite young

and a lot of R.N.V.R.s

among them. Just before dinner

the Commander gave me a few

casual instructions: (a) To

wear my "Mae West" all the

time, (I pointed out that he

wasn't wearing his and he

laughed gaily,) (b) That in

the event of any submarine

alarms and excursions the best

place to make for was the

Bridge where there is more to

be seen, and (c) That if there

should be a sudden loud bang

and a violent list either to

port or starboard I must pop

out on to the Quarter Deck

immediately and make for the

nearest Carley

Float of which I am also an

honorary member, there, he

added, I had better wait until

the order came to abandon

ship.

After

dinner I went on to the

Quarter Deck for a little and

watched the sea swishing by,

it was quite calm and there

was still twilight but the land.had

disappeared. In all my travels

there have always been certain

moments which stick in my

memory and this, I am sure,

will be one of them. I have

sailed away so many times from

so many different lands nearly

always with a slight feeling

of regret mixed with

exhilaration. This time there

was a subtle difference. I had

been in England for over two

years, a long while for me

ever to stay in one place, and

except for a brief trip to

Iceland with Joe Vian

in August nineteen forty-one,

and a few days in destroyers

here and there I have been

with the Navy very little

since the war. I felt aware,

strongly aware, of the change

in atmosphere, the switch over

from peace-time,

show-the-flag,

spit-and-splendour efficiency,

to this much grimmer, alert

feeling of preparedness

permeating the whole ship.

The

engines were throbbing, we

were doing about twenty-two

knots, and the wake churned

away into the gathering

darkness and I had a sudden

impulse to shout very loudly

with sheer pride and pleasure

and excitement.

---------

When

I woke this morning I looked

out of the scuttle and there

was the Convoy; grey ships,

grey sky and grey sea, not a

scrap of colour anywhere.

Made

a tour of the lower deck with

the Padre in course of which I

signed a lot of pay-books and

''best girls" photographs,

shook a lot of hands and had

several tots of rum from

everybody's mugs.

There

was some excitement early this

morning, apparently a Junkers

88 suddenly popped out of the

clouds at us. We opened fire

at once and it beetled off, I

was sleeping at the time with

"Quies'

stuffed into my ears and heard

none of it.

The

Commander has a perpetual

twinkle in his eye and speaks

excellent, rather ironic

English with a slight drawl.

When I asked him about

identifying aircraft he

explained that the only one he

had ever been able to identify

was the small model Focke-Wulf

attached to the mainmast and

even this, he added, was only

because of the knots that tied

it on. This inadequacy of his

he described as "lamentable!"

All

the evening there was tension

on the Bridge because an enemy

aircraft had been reported to

be somewhere in the area, but

nothing happened. My steward

takes a pessimistic view

whenever possible. He looked

gloomily out of the scuttle

this afternoon and said: "I

hope we shall get this lot

through all right" as though

there were very little chance

of it.

On

the Quarter Deck before dinner

I had an intense conversation

about sex, war, marriage and

life-in-the-raw with "Torps"

(aged twenty eight) and

another young officer (aged

twenty six) who is athirst for

knowledge and is forcing

himself to like classical

music. He turned on the radio

after dinner and listened to

the London Symphony Orchestra

playing Rossini after which a

lady proceeded with great

enthusiasm to sing the "Bell

Song" from "Lakme."

This shook him rather and he

gave up. (I think it was "Lakme"

but it might have been "Dinorah.")

Having,

in course of conversation

yesterday, told the Pilot and

the Commander about a

dreadfully hearty man in New

Zealand who used to greet me

regularly with - "How are we

this merry morn?" and "Good

morrow kind sir" I have

obviously laid up trouble for

myself. They pursue me with

these phrases incessantly.

Finished

the day with a cup of ship's

cocoa in the Sick Bay and a

long, at moments gruesome,

medical discussion with the

P.M.O., who couldn't be

nicer. I stumbled off

to bed down ladders and under

bulging hammocks at about

midnight.

---------

In

the afternoon all greyness

disappeared and the sun came

out, the air became distinctly

warmer and I lay on the

Quarter Deck on the

Commander's camp bed in a pair

of shorts and watched the sea

getting bluer and bluer. This

idyllic peace was shattered by

"action stations" being

sounded and the announcement

that a hostile group of

aircraft were coming in to

attack us. Everybody flew to

their stations, I dashed into

my cabin, hurled by clothes

on, collected my binoculars,

tin hat, morphine, “Mae West,"

ear plugs, etc. and was on the

Bridge inside of two minutes

keyed up for death and

destruction only to discover

that the group of hostile

aircraft had diminished into

one amiable "Catalina.". I

returned to the Quarter Deck,

stripped again and relaxed.

The

Commander had the “Malta

Convoy" film run through for

me in the men's recreation

room. A terrifying picture.

This ship was the only one

that got through without

casualties. Out of a convoy of

fifteen merchant ships only

five got into harbour and one

of these was bombed and sunk

when she got there. The

photography was excellent but

the commentary rather

tiresome, too much of "Our

brave sailor lads," stuff. God

knows it's difficult to

describe courage and gallantry

but it must not be done with

unctuous cliches.

---------

A

lovely morning, clear and

sunny and the sea still

calm. At about eleven

o'clock I went on to the

Bridge to say good morning to

the Captain and I hadn't been

there two minutes when a great

deal of excitement started.

First of all an enemy aircraft

was observed circling around

the convoy, then a submarine

was reported on the starboard

beam. Intense activity set in

immediately. I was given a tin

hat by the Commander as I had

left mine in my cabin; we

watched two escort vessels

dropping depth charges, a

dramatic sight with the spray

shooting hundreds of feet into

the air. We dropped behind the

convoy and proceeded to attack

the aircraft, the din was

terrific and the heat of the

gunfire from B mounting just

below the Bridge scorched my

neck. I felt singularly

detached and almost expected

to hear David's voice saying

“Cut.” It all seemed much

further from reality than "In

Which We Serve." I fell

automatically into my "Captain

D" postures, and it was only

with a great effort that I

restrained myself from pushing

the Captain out of the way and

shouting orders down the voice

pipes. We didn't hit the

aircraft I regret to say but

our shooting was straight and

it disappeared into some

clouds. I came below to fetch

my coat as it was a bit nippy

on the Bridge. To me, the most

depressing part of action at

sea is the closing up of the

ship. It feels gloomy and

lonely and scarifying. I

returned to the Bridge but

nothing further was happening,

there was no news of the

submarine and all the

excitement was over so, after

standing about a bit, I went

down to the wardroom, had a

drink and some lunch and then,

inevitably, went to sleep.

After

tea I went along with the

young Lieutenant who wishes to

like good music to the E.R.A.'s

mess. They were a bit shy at

first but warmed up after a

little and conversation flowed

and they plied me with

questions about "In Which We

Serve." They wanted to know

how much time I had had to

spend in the water and was it

real oil fuel or not and

countless other things. They

were all delighted with the

fact that the lower deck had

been presented in the film not

as comic relief but as an

integral and vital part of the

story. I asked them if they

had any technical criticisms

to make and they had none

which of course, was

gratifying.

-------------

I am

giving a show to the troops

this afternoon so I spent the

morning going over lyrics in

my mind and writing a new

topical Naval refrain for

“Lets do it." I expect Cole

will forgive me. After lunch I

sunbathed. No enemy annoyances

and a clear sky. One of the

escort vessels dropped a few

depth-charges but, I think,

merely for the devil of it.

At

five o'clock I gave my show in

the recreation room. At my

special request there were no

officers present, in a

confined space it is always

much better to have the men by

themselves. The piano was

unbelievably vile but they

were a wonderful audience,

eager to enjoy everything. I

went on for forty minutes.

Before

dinner the entire Wardroom got

into a literary argument in

the middle of which the

Captain's secretary, with eyes

blazing, went into a tirade

against Kipling. He shouted

"Tripe! Tripe!" with great

violence and I couldn't have

been more astonished as he is

a delicate-looking boy of

twenty-two, very retiring and

very very

Scotch.

I

gave another show at five

o'clock for the troops that

couldn't be there yesterday

and, in the evening, after

dinner, that vilest of all

vile pianos was carted into

the Wardroom and I sang and

played practically everything

I could remember. Personally I

felt that I went on far too

long but they seemed to want

me to. When I had finally

played my last chord and sung

my last note, the Commander

got up and said "I had

prepared a very flowery and

"ormolu" speech of thanks to

Noel Coward but I won't

embarrass either him or you by

saying it because I suddenly

remembered that in the Navy he

is one of us and he will be

the first to understand that

we never thank our own

people." I shall become a bore

if I go on any more about the

perfect manners of the Navy

but I must put on record that

that was the most graceful and

courteous compliment I have

ever had in my life.

---------

We

are arriving at Gibraltar